I recently had a chat with Khanya Mashabela, curator at the Norval Foundation, about a group show she curated; Mixed Company (on view until 31st May 2021).

My initial reaction to the exhibition was a discomfort with the title. The term “mixed” brings with it a number of complicated associations—thinking about ‘mixed’ as constructed through the possibility of fully mixing (solubility) and the impossibility of fully mixing (emulsion). With this distinction between soluble and emulsive elements, I’m taking instruction from a provocation by artist Nolan Dennis at the Holding Water conference which took place in 2019 at POOL, Johannesburg. I’m using Dennis’ provocation as a method to contemplate how various states of mixing can be articulated through a soluble vs emulsive framework. An emulsion is a mixture of two or more liquids that are immiscible—think oil and water. Each element can be temporarily suspended within the other, however, each remains unblendable. Solubility, on the other hand, speaks to substances that are able ‘to find a solution’—think sugar in water….there’s an equilibrium. I find this framework generative in thinking through Mashabela’s Mixed Company, which confronts us with a series of collisions presented through the eyes of eleven modern and contemporary artists from southern Africa: Omar Badsha, Jody Brand, David Goldblatt, Dada Khanyisa, Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, Musa N. Nxumalo, Leonard Matsoso, John Muafangejo, Kresiah Mukwazhi, Selby Mvusi and Gerard Sekoto. Through the exhibition, we’re able to consider forces and structures that allow states of solubility against states of emulsion —geographically, temporally and spatially, what does it mean to ‘mix’ ?

The exhibition is premised on various acts of gathering as a contemplation of mixed company, offering varying perspectives and readings on closeness, touching, joining, linking, mixing, combing, blending, connecting…

Below is our conversation.

Mixed Company installation photograph

Can you tell us about the title of the exhibition. How are you thinking through notions of gathering as “mixing” and mixed?

Khanya Mashabela: Though the exhibition is about social gathering, there are other underlying themes that are interwoven throughout. I came across the phrase “mixed company” while online, in reference to speaking about race in racially mixed company. It is a phrase that is commonly used as a warning, “Don’t talk about that, we’re in ‘mixed company’’”. I had been thinking about how large gatherings of Black people/people of colour are often looked at more harshly by authority. I had this in mind particularly as I looked at Musa N. Nxumalo and Dada Khanyisa’s works, but race features in most of the artworks in different ways.

And the exhibition is ‘mixed’ in many other ways: visual strategy and medium, historical period, social context.

You mention that the exhibition explores acts of gathering. When I hear the word gather, I think about holding, containing and vessels that allow us to hold and contain. This makes me think of holding with care, which in a sense is what curatorial practice is really about. Can you share with us a little bit about your curatorial approach for this exhibition?

Khanya Mashabela: In some ways, Mixed Company stands in for one or two larger exhibitions that I have been mulling over but haven’t had the time or resources to pull off yet. For that reason, it does feel quite loose-ended, which I think works in the context of a relatively small, thematic group exhibition. Mixed Company is a combination of artworks that were first exhibited in the past few years which stuck with me, recent acquisitions, very established artists like Gerard Sekoto and David Goldblatt who I wanted to reconsider, and twentieth-century artists like Selby Mvusi and John Muafangejo who I probably should have known already but who I found in my explorations of our art storage.

Visually, I really enjoyed the show. I was challenged by a few moments that seem to stress the divergence between artists, medium, scale or even artistic preoccupations? I’m wondering how you approached ‘dissimilarity’ within the show?

Khanya Mashabela: One of my favourite texts is Derrida’s Archive Fever, where he asserts that difference is inherent to repetition. Some of the exhibited works might feel out of sync with each other at first glance, but by placing them together I can emphasise the less immediately obvious visual elements that they share. For example, Muafangejo’s visual language is very different to Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi’s. However, they both use a similar aesthetic device, portraying all of their subjects as slight variations of the same person, to downplay their individuality. From Nkosi, this feels wholesome and unifying, while from Muafangejo it varies as a condemnation, a show of strength, or a display of shared grief. I learn more about art — and creative expression in general — from these juxtapositions.

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, Ceremony (2020) Homestead Collection

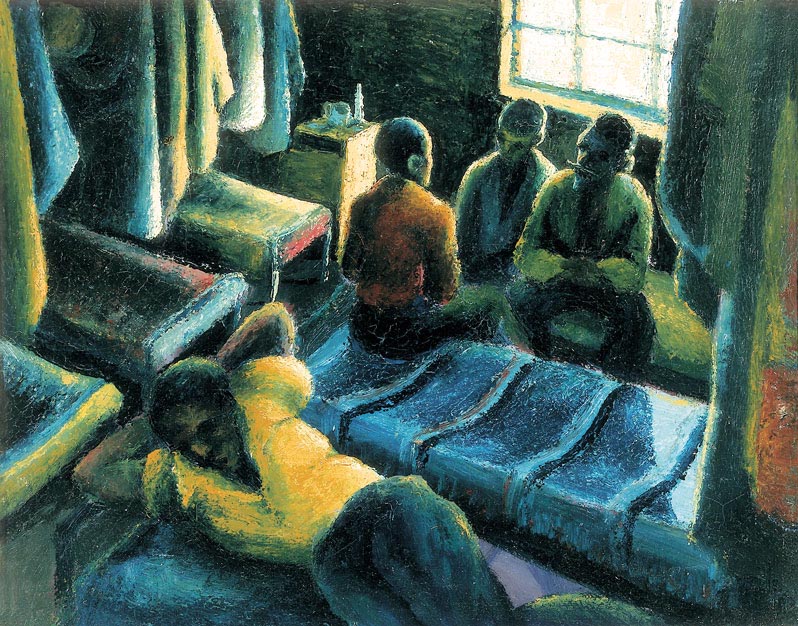

The show is beautiful in that it foregrounds presence – we see the gathered bodies; the workers (Goldblatt), the gymnasts (Nkosi), the dancers (Muafangejo) and Sekoto’s gathered figures under ominous light. But I’m thinking about absences too, particularly in relation to the global pandemic. What was, what no longer is and also what never was for others – the idea that for some people the pandemic has really not affected what it means to be included/excluded as they have always rested on the margin. How are you thinking through absences, if at all?

Khanya Mashabela: There is another juxtaposition here. I think that we can understand absence through presence and vice versa. Humans are social animals and I think that most people have experienced yearning. That might be especially true for people who exist on the social margins. Some of the works are personally interesting to me because they depict forms of idealised closeness and belonging that I don’t have. That feeling of yearning will come to viewers in different moments and for different reasons. The pandemic makes these feelings of intimacy and yearning feel more immediate and relevant, but they have always been there.

Gerard Sekoto, Workers on a Saturday (1941) Homestead Collection

The works in the show span across 80 years (roughly). That is both long and short. Can you talk to us about time, in relation to this exhibition?

Khanya Mashabela: Because the exhibition is thematically focused, rather than an attempt to create a ‘rationalised’ account of southern African art history, time is flattened. In some ways, the human condition has not changed so much in the past eighty years. It was also an assertion of the continued relevance of artists like Leonard Matsoso and Selby Mvusi who had fallen out of the undergraduate university curriculum, as I had experienced it.

But also, I have been wondering why the exhibition feels more ‘heavy’ than I had initially intended. I realised that it exhibits eighty years of consistent social interaction from the perspective of a society that has now experienced a historic disruption. We are still anxious about whether or not we will get the sensations depicted in the exhibition back again. So while the exhibition shows celebration, revelry, and unity, it is tinged by the anxiety of an uncertain future.

This is an unfair question but I’m interested to know if there is a moment in the exhibition that feels particularly personal and resonant to you? Whether it is a specific work, a group of works, a corner etc?

Khanya Mashabela: It changes every day, depending on what I am yearning for the most. Some days I am most struck by the comfort I have found in work relationships in this strange time, so I am fascinated by the wall that shows portrayals of this relationship by Sekoto, Goldblatt and Mvusi. On other days, I desperately miss the sense of group belonging that came from the culture of nightlife, seen in the pieces by Dada Khanyisa, Kresiah Mukhwazi and Musa N. Nxumalo. I’ve experienced some familial loss and near-loss recently, so Jody Brand’s take on a family portrait has really been resonating.

Jody Brand, All that you touch You Change. All that you Change. Changes you. (2018)