Abstract:

You said, “Excuse me, am I in the way?” Knowing all the while that you were the way. You had this canny ability to shape an untenable reality, mold it, sing it, reduce it to its manageable, transforming essence, which is a knowing so deep it’s like a secret. In your silence, enforced or chosen, lay not only eloquence but discourse so devastating that “civilization” could not risk engaging in it lest it lose the ground it stomped

Morrison, 1985.

The piece that is to follow elicits a meditative conversation with the visual art of Puleng Mongale. I call upon Audre Lorde’s poem a litany for survival (1978), as my companion in this contemplation. Mongale’s visual art and praxis and Lorde’s poem placed alongside each other; sisters from distant shores standing side by side in a family portrait.

I think of Puleng’s work, in the tradition of Black femmes as Witch Work. Her collaged assemblages; healing spells cast through memory work and an intimate subversion of the archive. Unfiltered, unfaltering and unafraid collaged compositions; synthesized in the space between rawness and vulnerability, that attempt to excavate truth in something or some form of honesty.

“Can [B]lack people be loved?” asks Afro Pessimist thinker Fred Moten, “not desired, not wanted, not acquired, not lusted after… can [B]lackness be loved?” In a way that does not seek to mystify, deify or romanticize the history, condition and state of [B]lackness, Puleng’s collaged love letters are the yes whispered and ululated in the break.

Dear Reader,

I find myself feeling almost apprehensive and tip-toe-hesitant to put words to Mongale’s Witch Work made manifest through her visual artistic praxis; language is often too porous a vessel to hold all of the stuff our magic carries. Too much gets lost in translation; reduced to dry, simple matter. In our first moments of seeing each other since 2017, we muse over how heavily pregnant with her son she was. Along with little Wame, Puleng has birthed and offered so much in the time and seasons past to this moment.

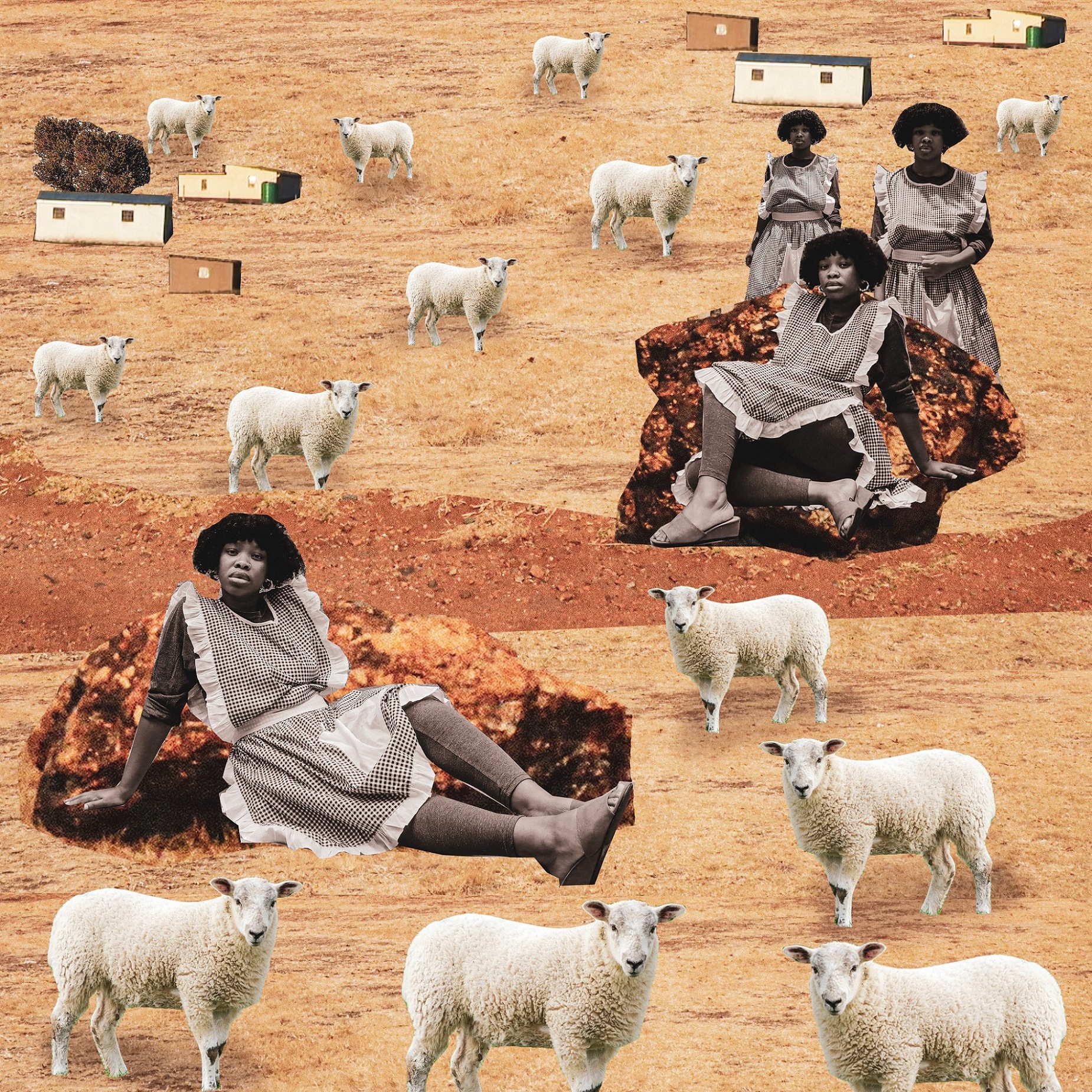

I first came to encounter her work through her conceptual and stylised 4 part series titled Intimate Strangers which interrogated conditions of Blackness within the historical and socio-political ecology of South African society. Specifically When the Madame is Away, the Help will Slay; a series of stylised portraiture exploring the space and legacy of domestic work within South Africa by virtue of visual social commentary.

With figures clothed in garments quintessentially associated with domestic work in South Africa, which Puleng had received from her grandmother in the Free State (initially given to her grandmother by her boss), “I feel like my grandmother’s house is a museum.” (Puleng Mongale).

Untitled, Puleng Mongale.

Puleng’s art does the work of thawing and re-figuring intimate and grand cultural narratives and symbols from the cold clasped hands of history with a capital H. With each new moment I spend in contemplation of and with Mongale’s work, I am served an abundant offering of new feeling with which to map my relationship with my own ancestral histories.

I’m trying to figure myself out and realising that it doesn’t start with me, you know? Cause I was also having a conversation with my mom and I told her; I’m not the first talented person from this home, I’m just the first to sort of go out there and pursue it because you guys had to work. There was no time for dreams (Puleng Mongale).

Speaking about her four part series Intimate Strangers, I was surprised to learn from her of the backlash she had received in reaction to When the Madame is Away, the Help Will Slay. To me this body of work specifically read as a kind of lament of the invisiblised labour and commodification of Black humanity forged within a violet history, and simultaneously as an ode to the subjectivities of our great grandmothers and their daughters who made life within those spaces.

“Even my mom was a domestic worker at 19 and she’s not a sad story… this is my grandmother’s story, this is my mom’s story” shares Mongale. However, others criticised it for being a glorification of domestic work and omission of its other dark facts; how mournful the possibility that we have so fully consumed the lie of the big white whale that postulates suffering as the only scent carried by our lives?

Untitled, Puleng Mongale.

For those of us who live at the shoreline

standing upon the constant edges of decision

crucial and alone

for those of us who cannot indulge

the passing dreams of choice

who love in doorways coming and going

in the hours between dawns

looking inward and outward

at once before and after

seeking a now that can breed

futures

like bread in our children’s mouths

so their dreams will not reflect

the death of ours;

There has been a noticeable stylistic evolution in Puleng’s work since Intimate Strangers. Her collaged assemblages, which can also be read as reflexive self-portraiture, collapse the binaries of Object/Subject/Creator. One could say performing the very socio-historical condition of Blackness where there is no distinction between the private and the public.

The use of her own self and body in their composition found the artist along the way.

At some point I was like I want to buy a camera… I do like capturing other people but most of the time I would rather capture myself. Because I feel like then, I can take full accountability for whatever it is that I’m putting out there. I’m becoming the subject and saying actually whatever the scrutiny, whatever you have to say it all falls back onto me. I was also telling somebody that I’ve got a strong link with ancestry.

I can’t always articulate it but I feel like in creating the work that I do, I’m always just trying to understand those who came before me. I’m also named after my great-grandmother and I never got to meet her and there’s literally only 3 pictures of her at home, she looks nothing like me except for the lips… I’ve yearned for so long and wish that I had known this person but I do sometimes feel her in me… It’s also very deliberate in that I’d notice a lot when going through family albums how so much was never documented.

A collaged brave space of creation imbued with a raw vulnerability, where visual socio-historical mediations also function as an intimate self-reflexive visual journal and conversation with her ancestral lineage.

Untitled, Puleng Mongale.

the heavy-footed hoped to silence us

for all of us

this instant and this triumph

We were never meant to survive.

…

So it is better to speak

remembering

we were never meant to survive.

A gathering of the past and the present. Compositions of fabricated time travel. A way to foster a relationship with her Basotho heritage which she could not always openly explore growing up in Orlando East, “even ko Kasi you can be othered, you know when you come to Joburg Zulu is the thing!” Puleng excliams between laughter as we talk.

Mongale’s work leaves no hidden corner in which she can hide, her visual portals between our physical world and the ancestral plane feel in moments as if they were created in communion with those she is attempting to know and call upon. “I imagine things a lot and collages have helped me do that, they’ve helped me put together pieces of worlds that I’ve never been a part of and worlds that I’m trying to forge right now” she shares with me as we start to wrap up our bountiful conversation.