My week in the Goodman Gallery’s online viewing room: worrying about shebeen queens, the pleasures of home viewing and new coping mechanisms

On Monday, a police officer with an automatic weapon was prowling about the entrance of my building. Unnerved, I rubbernecked over the balcony and saw that he was standing guard over a forensics van. Someone must have passed away. This was later confirmed by the chemical smell wafting from the elevator. Glum, my senses sore, I stalked the internet for a spirit-lifter and chanced upon the Goodman Gallery’s online programme.

There is William Kentridge, Something Has Been Postponed (more on him later), there is Authenticité (recently reviewed by Rory Tsapayi) and there is Sense of Place. The latter brings together fourteen artists with far-reaching interests in the concept of “place”. I planned to skim through to distract myself, but instead returned everyday.

Peter Magubane, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela under house arrest at number 8115 Orlando West, Soweto, c1969. Silver gelatin print.

What a face, what a photograph. Ironically, under house arrest MaWinnie found herself more at risk than her husband on Robben Island. Here she describes a typical raid on her house:

“…that midnight knock when all about you is quiet. It means those blinding torches shone simultaneously through every window of your house before the door is kicked open. It means the exclusive right the Security Branch have to read each and every letter in the house, no matter how personal. It means paging through each and every book on your shelves, lifting carpets, looking under beds, lifting sleeping children from mattresses and looking under the sheets. It means tasting your sugar, your mealie meal and every spice on your kitchen shelf. Unpacking all your clothing and going through each pocket… Ultimately it means your seizure at dawn”

Being unsafe in your own home is not new in this place, even if it shape-shifts. Addressing South Africa on day 48 of one of the most severe lockdowns in the world, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced efforts to protect women during this time, acknowledging the gender-based violence ravaging the country. “Men have declared war on women in South Africa,” he said.

In 1969, South Africa’s still-not-fully-acknowledged war was gaining steam and Madikizela-Mandela spent 18 months in solitary confinement at Pretoria Central Prison so this photograph must have been taken just before. Peter Magubane was sent by the Rand Daily Mail to photograph a demonstration outside her prison cell, only to be apprehended and arrested. He spent 586 days in solitary confinement.

Poring over this photograph, I thought as much about him as I did about her. When Magubane was released, he was served with a five-year banning order and arrested and jailed numerous times after. Talking to the NY Times years later about how he would scoop out the middle of a loaf of bread and put his Leica inside, pretending to be eating because the apartheid government had banned the press: “If you want a picture, you get that picture, under all circumstances.”

On Tuesday, I tried to spend time with the artwork by William Kentridge, included in this collection but couldn’t shake Kneo Mokgopa’s review of the artist’s 2019 exhibition at Zeitz MOCAA. Mokgopa unpacks how Kentridge uses the Black body as the symbolic site of South African history, reducing the struggle against oppression to “antics in a Vaudeville production”. Mokgopa is concerned with conjuring a ‘there’ where there has been ‘unthere’ (in this case the hyper-invisibility of Black bodies in white art spaces). Their observation of the bizarre absence of whiteness in the iconography of Kentridge’s recent shows, and the normalised disregard of Black presences in white art spaces (like the security guard outside the museum, ignored by all) is an astute meditation on cultural place-making. The artist’s contribution to this exhibition is an innocuous landscape sketch, but when Toni Morrison said she writes towards Black people, she also pointed out that Tolstoy was not writing for her. I am wary.

Robert Hodgins, Sorry about the retrenchment old man!, 2004. Oil on canvas.

Instead, I turned to Hodgin’s and thoughts about retrenchments. According to Guy Ryder, Director-General of the International Labour Organization, “this pandemic has mercilessly exposed the deep fault lines in our labour markets.” Elisha Kunene summarised this well: “The richest people in the world are using Covid-19 as an opportunity to complete their victory over organised labour.”

In the 1980s, Hodgin’s started satirising figures of power by depicting malevolent businessmen in vivid colour. Political tyrants and business fiends are iconic in his work but it was the colour in this painting that compelled me.

On Wednesday, I stayed with Hodgins, this time a painting with Jan Neethling.

Robert Hodgins and Jan Neethling, Just Us Two, 2010/2016. Oil on canvas.

Last year, Wits Art Museum (WAM) had an Hodgins exhibition, A beast slouches and so forth which tackled the paradox of a world in which extremes of beauty and horror co-exist. I thought about that duality looking at this love story, thinking of the romance and heartbreak of pandemic partnerships.

The partnership behind this painting is a charming one. Jan Neethling painted prolifically, exhibiting as early as the 1970s but almost always in collaboration with Hodgins. He was perceived by many as in the shadow of Hodgins, who became one of South Africa’s art stars. Neethling was 70 at his first solo show in 2008, and insists that he is “an emerging young artist”. Hodgins only made it into the big league around the same age. According to Neethling, 70 is a good age to get serious. Once more, it was the colours in the painting that got me, jumping out and sitting still simultaneously. The story isn’t clear but man is it expressed.

On Thursday, I missed my friends and ‘Sheila’s’ which is what my parents call partying on Thursdays, shorthand for ‘Sheila’s day’. Thursday was the day off for domestic workers during apartheid and ‘Sheila’ the name used by South African white women for domestic workers, claiming they couldn’t remember their real names.

On a normal Thursday, I might be in a Johannesburg bar but that is of course neither possible nor desirable. Instead, I long for the drinking days of youth: quarts of Black Label beer from aunty Daphne, Shebeen Queen of Maraisburg, in the open air of the park down the road from my parents’ house, looking over the mine dumps of the West Rand.

Sam Nhlengethwa, Shebeen Queen (Madi Curves), 2016. Oil and collage on canvas.

In popular discourse today, Shebeen Queens are favourably represented, perhaps nostalgia for Miriam Makeba in King Kong, perhaps because the establishments they lord over are now legal and the alcohol sold is much cheaper than elsewhere. But shebeens are subject to the same taxes and legislation as all legal liquor-serving establishments, except with heavier social tolls. Many are still run and owned by women, many are still perceived as public nuisances.

I love that the woman towers over the men, that she too has a cup in hand, that hers is the only well-defined face. There is much to love in Sam Nhlengethwa’s work, South Africa’s collagist-pioneer not because he is the first or the only artist working in this medium, but because of how he uses hard-edge cut shapes to make soft scenes.

I don’t love that outside of writing on the apartheid-era illicit alcohol trade, scholarship on Shebeen Queens is nonexistent. I want to see these women in more contemporary art, to know more about their place in contemporary society. I’ve also been wondering about shebeens as a site of future waves of coronavirus infections.

Recently, I’ve been reading Ruth Wilson Gilmore and others working on Black geographies. Gilmore, an abolitionist and prison scholar, writes about how racial hierarchies are upheld by the spectre of the “Welfare Queen”, the stereotype of African-American women leaching off the state and producing criminal offspring that need to be locked in cages. Will Shebeen Queens become South Africa’s Welfare Queens in the Black geography of this disease?

On Friday, I read that “home is wherever you are not a stranger to yourself” so I did my hair and sat in the sun to feel like myself again, thinking about Sarie doing the same.

David Goldblatt, Sarie Fink doing her hair; she lived with her aunt, who farmed here at Klein Rivier, Buffelsdrift, between Oudtshoorn and Uniondale, Western Cape. 23 November, 2004. Digital print in pigment inks on cotton rag paper.

On Saturday, I was surprised to realise that of the fourteen artists in this room, two are women. I am annoyed by this example of how normal it is for men to dominate by institutional design; not because I want all-woman or all-queer or perfectly-gender-balanced exhibitions but because I genuinely hate feeling disappointed like this and I expect cultural institutions to do better.

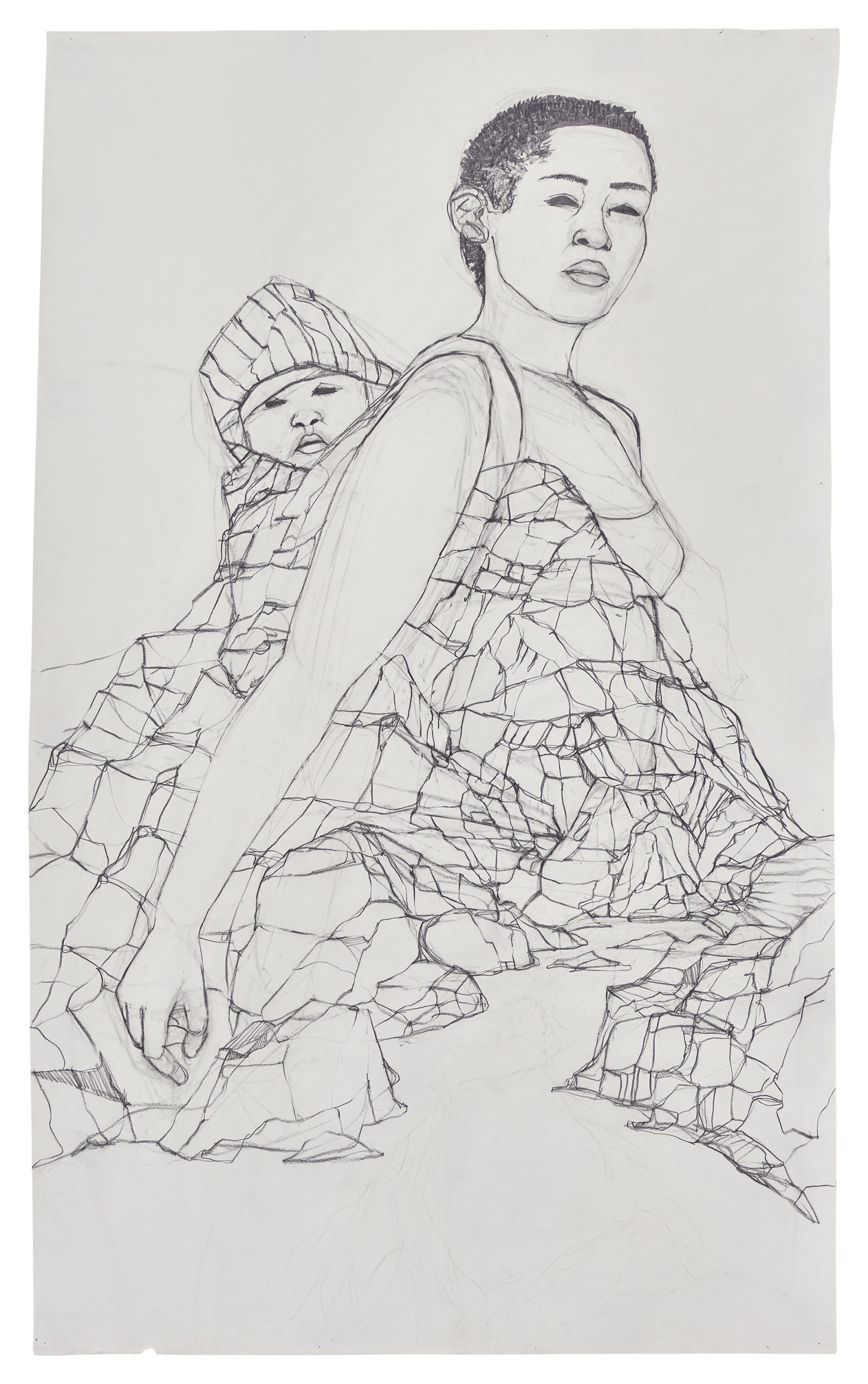

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Untitled (Mountain, Mother, Baby), 2015. Mixed media on paper.

This is the only artwork that I long to see in real life. At first glance, a simple sketch until you notice what Alix-Rose Cowie calls the “veil of mystery”, the way objects, subjects and landscapes are painted over in layers “as if each is drawn onto transparent paper and placed in a pile.” I feel cheated by the photograph, I need to pace back and forth in front of the real thing, studying it’s geomorphology.

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum’s multidisciplinary work alludes to mythology, geology and theories on the nature of the universe. Her drawings are narrative landscapes, a down to earth but cosmologically wild visual version of what Keorapetse Kgositsile referred to as ‘PastPresentFuture’. Sunstrum’s representation of time-space intrigues, as does this statement: “Etched in the body are the narratives of the landscape.”

On Sunday, I looked at this image and realised I haven’t seen a child in fifty days.

Kudzanai Chiurai, A few hours later, 2020. Oil on canvas.

Keeping kids indoors is necessary but life without them is eerie. I have no idea what children think about this pandemic, reminding me of a n+1 panel on Parenting and Climate Change. One panellist described struggling to understand why her children were unfazed by global warming after watching a climate change movie, only to realise that at the end of the film, the narrator says the adults are going to be meeting very soon (the movie was made just before the Paris climate conference). Her children were unfazed because they assumed the adults had it under control, that they had a plan. There is something about the expression of this boy that is both unfazed and well aware that the adults have no control, no plan.

Kudzanai Chiurai incorporates various media into his practice, largely focusing on cycles of political, economic and social strife in postcolonial societies. Interrogating colonialism then upending what he calls ‘colonial futures’ is the name of Chiruai’s game. For example, reimagining postcolonial struggles with women centred instead of sidelined. As far as I can tell; Chiruai does not include children in his work. I am curious about why he did now? Following Mokgopa, I am also curious about the ‘unthere’ cultural places that children are in during this confusing coronavirus time.

In a recent interview, artist Nolan Oswald Dennis describes how

“breathing through the anxiety of not knowing whether galleries, museums, art fairs, theatres, bars, clubs, classrooms will survive this crisis – and the social health and economic priorities that follow – cultural workers still have to find ways to produce work as if this infrastructure will still be there… as if this crisis is a postponement rather than a remodelling of the way things were a few months ago.”

This is a collective anxiety not only for cultural workers, but consumers too. My internal software is still trying to integrate with my external hardware forced to stay inside; to be still. Like the exhaustion of oscillating between hyper-productivity and lethargy, I am confused by extreme binging (a novel a day) and struggling to fire neurons (four days to write two paragraphs). After another weird week, starting with the sensory stress of being disembodied by a body outside, I am grateful to discover that my coronavirus-sense-of-place and it’s defining quality of a displaced sense of self/society was assuaged by very targeted, intentional consumption.

Ben Eastham has reflected on the pleasures of home viewing, a reprieve from the spectacle of socialising associated with air-kissing in-person art-viewing and a relief from class barriers, digital distance from the reality that much in the art world “is reserved for those who live in the cities where it is exhibited, have the resources to own it or were brought up within its codes.” If not yet a pleasure, I now appreciate online viewing as a crutch.

Legendary art critic Jerry Saltz recently penned a beautiful essay about coping mechanisms. There is this comforting anecdote: on the night that his wife (Roberta Smith, also a celebrated art critic) was diagnosed with cancer, they spent the night talking about “the connection between Matisse’s late paper cut-outs and how Donald Judd uses colour in his last works”. He candidly describes how art saved them that night and saves them today, pandemic notwithstanding.

“We knew that art and writing about it had gotten us to this point and that it could be what got us past it.”