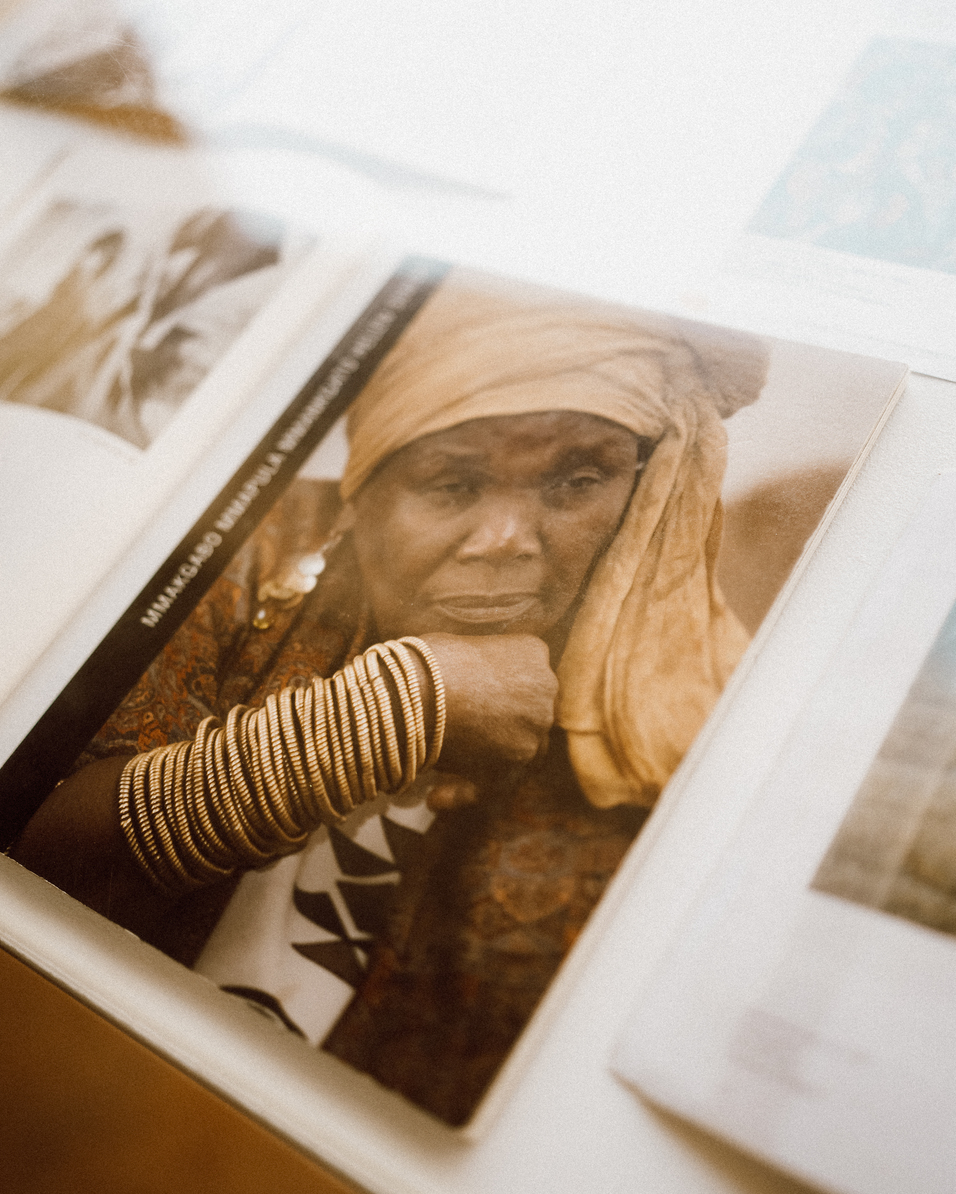

The scene was set. It was early afternoon and the Joburg sun was uncannily serene. At the far end of the UJ Art Gallery, Dr. Thembinkosi Goniwe sat next to Mme Mmapula Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi under the watchful eye of Dr. Kholeka Shange. A group of keen students sat in a semi-circle around the pair, joined by curious community members like myself. One could almost hear a pin drop as Mme meandered through her stories as if she was telling inganekwane around a kraal fire. In an instant, it was as if she was ours and we were hers.

Born on March 5, 1943, in Marapyane, South Africa, Mme Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi is a national treasure whose vibrant paintings and sculptures often depict rural experiences and life under apartheid. Trained under Jonathan Koenakeefe Mohl, Mme Sebidi has received awards such as the Standard Bank Young Artist Award (1989) and the Order of Ikhamanga in Silver (2004). Her work is featured in prestigious collections like the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, and she has exhibited globally, including at the Venice Biennale.

Unlike many walkabouts, this was mostly a seated affair and the pace was discrete. Seated comfortably on an armchair, Mme Sebidi took her time and reflected on the experiences and philosophy behind her work. She emphasized community, communication, self-reliance, and cultural integrity, sharing anecdotes of support and advocating against colonialism. She spoke of her challenges through her art practice, motherhood and domestic work, with the kind of grit and detail that can only come from the horse’s mouth.

Intermittently, Goniwe interjected, “It’s not just about being able to think, form, and create … but also about the importance of those forms when they are completed and designed … expressed in beautifully simple language. … Like the word she used: love. This idea of caring for each other, a kind of selfless love. … It’s sad when these forms of love and care, common to indigenous abilities around the world, are misled or misused … Communities formed by these values are difficult to develop, but they expand our potential. … When you look at her work and listen to her, you find a resurrection of these ideas. …”

Even though she travelled the world through her art, Mme Sebidi’s creativity began at home and she saw examples of art and artists all around the various communities she inhabited. This led to a deep appreciation for art, particularly women’s work. She says she was given space to experiment and was always curious about image and form. “I was trained from a very young age,” she said, mentioning the influence of her grandfather, also a revered artist, whose cultural and spiritual legacy continues to inspire her.

But Mme’s artistic path was anything but simple. “I had to work as a nurse. … And my knees (hurt), because we had to kneel.… I got (a new) employer (to become a domestic worker) … Because I’m a real and active person. And not wanting to stop working. … we were even working at night. So (domestic work) for me was nothing. … I did baking. Then, as I was cooking, my feet got sore. … I was in pain and not even feeling that I could walk … I learned a lot … I worked for English. I learned English … able to see … how white people live …”

Despite hardships, Mme Sebidi found strength in traditional values instilled by her grandmother, reflecting on ancestral dreams as her guiding light amid personal challenges like her grandmother’s illness, encounters with law enforcement and pregnancy. She recalled the support she received after her son’s birth and acknowledged her family and mentors who stood by her despite her internal conflict and desire for autonomy. As she worked so hard, she was separated from her children for years, but the thought of them always gave her strength.

Through her various experiences as a domestic worker, she became exposed to the notion of becoming a professional artist. One of her employers was a keen artist and she recalled, “I didn’t know she was an artist. She had all the tools … So she started working on tie-dye, and I followed. Then she started working on … painting, I kept on taking … in anything she did.” From there, her passion for art grew, and her family always supported her. “I kept on doing my work.” Eventually, collectors began noticing her and the rest is history.

Mme spoke of how even though many people helped her become an established South African artist, she had always known that art was nothing new, but rather, a long tradition to which she intended to contribute. “Painting and sculpture aren’t just trends; they’re about our own expression. Women admired men’s architecture and saw opportunities for improvement, just like with sculpture. It’s about enhancing what we have and using communication as our voice. Education has had its impact, but we must remember the value of what we learn here.”

Throughout the session, Goniwe skillfully allowed Mme Sebidi the space and time to recount her stories and articulate her practice in her own words. He seldom interjected, only doing so to remind the audience of the importance of connecting Mme’s experiences to too often whitewashed art history, which sometimes fails to account for the intimate memories of living legends like this. At 80 years old, Mme Sebidi provided a unique opportunity to witness South African history from someone who had not only lived it but mastered the art of depicting it.

On one hand, this was no ordinary conversation, but a priceless audience with one of the most renowned painters in South African history. On the other, it was extraordinarily ordinary. Like sitting at your gogo’s feet, or listening to a typical Black South African woman who had accomplished so much despite so many hardships. Her resilience is remarkable and her resourcefulness so familiar. As one looked around the room at the young students listening intently to her tales, one could clearly see that her influence would continue to shape South African art for decades to come.