Curated by Joburg and Paris based multidisciplinary artist, composer, DJ and producer, MO LAUDI —Ntshepe Tsekere Bopape — Globalisto. A Philosophy in Flux, is a group exhibition of 19 artists, activists, philosophers, change-makers, storytellers and poets interconnecting Africa and its diaspora — spanning from Cameroon to Egypt, Gabon, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, South Africa and Tanzania but also Europe, the Caribbean and the United States.

The exhibition invited intergenerational artists who invent new worlds and question the status quo of current modalities, who critique power systems and interrogate biopolitics and multidimensional exploitation of resources into its curatorial multiverse.

Globalisto. A Philosophy in Flux evokes concerns rooted in Black aesthetic(s), ideas of a borderlessness and of how we can create new philosophies. How we can create new — rhizomatic — modalities of creation, interrogation, disruption, intellectualisation and orientation.

What does it mean to fabricate a space of holding, contemplation and engagement that is given texture and feeling by the works and modalities created and inhabited by the artists encapsulated within the fold of the show’s curation?

What possibilities of newness, borderlessness and of radical aesthetic(s) — as a philosophical praxis against the invisibilising and genocidal impulse of white capitalist hegemony and supremacy — become unearthed in this house of experimental provocations? How might interrogating history, apartheid, slavery and identity through Gerard Sekoto’s Song of the Pick placed alongside Dread Scott’s What is the Proper Way to Display a U.S. Flag? Alter or prod at our understandings?

MO LAUDI shares:

I created the word ‘Globalisto’ considering unification rather than separation, how the inner self creates the outer form. It’s a philosophy of feeling, caring, repair but also of strategies to occupy spaces and change the status quo. It’s a philosophy of connecting the practical with the metaphysical, the spiritual and the unseen — like sound.

Below is the conversation between myself and the show’s curator MO LAUDI, whose practice explores philosophies inspired by African knowledge systems, Black speculative movements and post-apartheid transitionalism in relation to a socio-political critique of society about Globalisto. A Philosophy in Flux.

Lindiwe Mngxitama: I want to start with the name you’ve chosen for the exhibition, Globalisto. A Philosophy in Flux. I think of it, and I am transported back to a previous conversation writer Nkgopoleng Moloi had with Editors Luamba Muinga and Sara Carneiro on their collaborative, multilingual and transnational digital project; Are we not makers of history? Particularly when she says of the digital project:

Rendered in book format, the project brings together a group of artists, writers and makers to explore historical legacies of colonialism, civil war and apartheid. By pointing to the ways in which history and identity are a never-ending project

There is something in the curatorial pulse of Globalisto. A Philosophy in Flux; in the artists who make up the fabric of its DNA, the disparate yet complexly interconnecting/interconnected geo-political and socio-cultural contexts from which they come and their modalities of working — especially when thought about in relation to the exhibition’s title and the Fluxes movement of the 1960s it evokes — that seems to make a statement or stake a position on how the show seeks to think through H/history, cultural production, identity and its making and genealogies of conquest.

What would you say this positioning is and is it one that can be defined in uncomplicated/complicating language?

MO LAUDI: The Globalisto philosophy is a philosophy that I’m working on. I created the word “Globalisto” considering unification rather than separation, how the inner self creates the outer form. It’s a philosophy of feeling, caring, repair but also of strategies to occupy spaces and change the status quo. It’s a philosophy of connecting the practical with the metaphysical, the spiritual and the unseen — like sound.

It’s evoking African knowledge systems, Achille Mbembe’s notion of a borderless world, and Buddhist principles of how when you put a stone in the water, there are ripple effects, what happens on one side of the world affects the other. How does one think from a Black Consciousness movement? From a Post-Apartheid Transitionalism school of thought perspective? How does one embrace Ubuntu while also critiquing it? It is us picking up where Pan Africanism and Negritude left off, remembering how they challenged the colonial system but also asking why Senghor thought French Africans would be better off within a French structure than as independent free nations. It’s being ready for a new era — accepting that these borders were not made for us — it’s remembering that we are here today standing on the shoulders of giants but these giants had weaknesses too.

One of the main ideas of the Fluxus art Movement of the 60s and 70s was to focus on the process, rather than the finished product. This is one idea that came to mind whilst I was giving a masterclass at Beaux Art school of Fine Art in Nantes, invited by my dear friend Charlotte Moth, with whom I later worked with on an exhibition called Decalage. I created a sound installation called What did Chris Hani say to John Cage, connecting my political engagement with the artistic practice of the process. The work is an ongoing process as Fred Moten says, “refusing completion”.

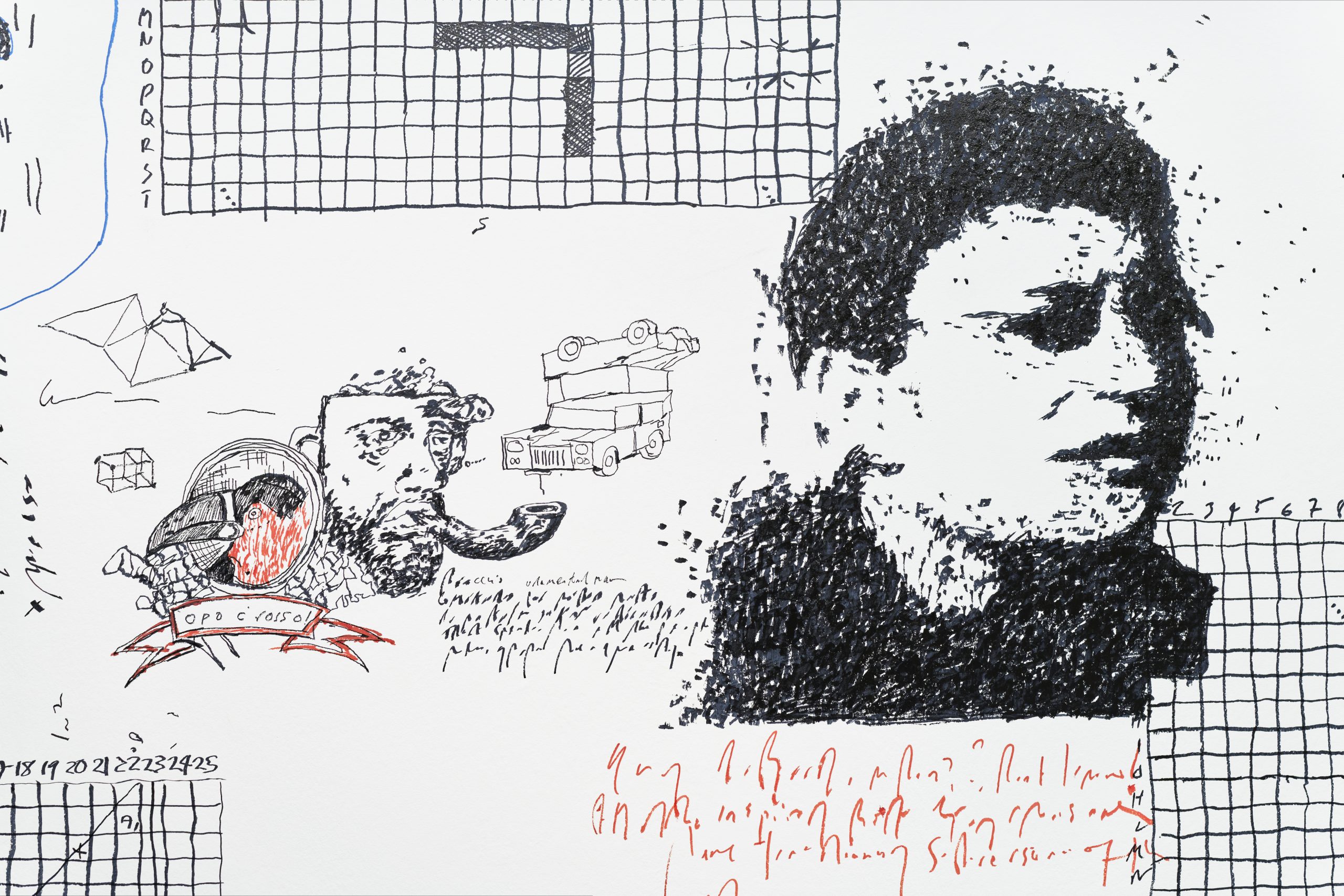

The Globalisto philosophy is in a fugitive state and refuses completion, refuses universalism, refuses to be a single being. Flux is that process, the constant sense of awareness. When you look at the work of Moshekwa Langa, you feel that sense of the process in his Drag Paintings as he allows the landscape to “draw itself” by dragging the material on the environment at the back of a vehicle, maps like traces of the land are formed on the fabric as contact is made, ‘the soil imprints itself’. The land being a contentious subject in South Africa, where families have been moved because of the Native Land Act, where capitalism forms new ancestral dislocation and mines are allowed to operate instead of nature.

This refusal to be a single being, what Édouard Glissant calls opacity, is one of the mycelium networks within the exhibition. The artists are interdisciplinary, working in installations, video, performances etc, their works have been questioning these issues for some time, some for decades, highlighting that decolonisation is a process and that we are not yet there. Sam Gilliam protested the museum’s lack of Black consultation in a show about Black artists, yet, when you look at his work — one would think it is free from politics but it’s free from the canvas. It’s questioning these inherent legacies within the systems today, ingrained in the social construct that we believe to be true when they actually aren’t. Cultural production against the mutilation of resources by the west, where you find artists of African origin refusing to be called “African artists”.

Why can’t they be artists? Why can’t this exhibition just be an exhibition without the connotation of being African? I found some fear in that, that immediately when you are labelled, you are boxed. As an artist one must refuse to be boxed, there is a thread, the lineage of deconstructing these old narratives, yet creating a moving network with the diaspora. A lineage of struggle and protest, but yet eludes definition

Lindiwe Mngxitama: How did you move, think, feel and play through curating the exhibition, was there a clear beginning from which you started and end you wanted to reach or was it more a case of the show taking form in companion with the artists, their processes and their works?

In the same way Toni Morrison spoke about the characters of her literary works announcing their names to her before she could fully begin to imagine and write their stories…

MO LAUDI: It is both ways, some of the characters of the exhibition announced themselves before the story of the movement, scenography or the architecture of the show was conceived, The song of the Pick by Gerard Sekoto — is one my favourite paintings in the world — was there in my mind since childhood. I wanted to pay homage to this hero who came from Limpopo to Paris to make his mark, I follow in his footsteps but with this being an exhibition in a museum, with the second biggest collection of modern art in France, I knew I had to dig deeper.

At the start of the exhibition, there is a reading area where you can find Gerard Sekoto archives that I found in Maison des artist, Paris, the last place he lived before his death. In this section, there are also Drum Magazine issues from the 60 to the 70s. There are books of philosophers and writers, such as Franz Fanon and my friends Norman Ajari, Elvan Zabunyan, Christine Eyene, Jamika Ajalon, Pascale Obolo, Rhoda Tchokokam and N’Goné Fall, Potiron Amal Alhaag — who all participated in the exhibition’s symposium. The curatorial concept of Globalisto philosophy was also there at the beginning.

Chinua Achebe, states: “Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” One could make the claim that still today, most Africans look at African history and identity through a European lens. Thinking of our shared disparate histories, the political resistance on one underground level, the spiritual on another level, and then the sheer explosion of form creating aesthetic bliss on another also informed the curation of the exhibition.

I thought through sound production and music composition in many ways. Not just the sound you hear but also the sound you feel; the sound you can see; where the notes hit; where the silence is; how we create a groove; to have complex syncopated drum patterns; the repetition; how that can be represented visually? There was also thinking through how sound traverses borders politically. I thought about which of my friends I could include in the exhibition, about who my community is, and who I like. How can I have equal representation of women and men? How can I give a chance to new voices? How can I occupy the space and challenge myself to do something that I have never done? How can I challenge the artists, the museum and our ways of unlearning so we can grow together?

Before the first reading room, there are bubblegum flags by Samson Kambalu, who has now launched Antelope on the fourth plinth of Trafalgar Square. I thought of a conversation I had with Raphael Barontini, about the hanging of his beautiful work, how that was different before and this time — about how it was in dialogue with Sam Gilliam and Moshekwa — only to discover that Raphael and Moshekwa are friends and that Raphael is highly inspired by Sam Gilliam.

Speaking to Josefa Ntjam, it was interesting to find out that her gorgeous work has been shown a lot next to Otobong Nkanga’s, and as you move to the exhibition’s second room this is the case yet again. It was gorgeous to see how Sammy Baloji’s work, archival photographs of German anthropologist and ethnologist Hans Himmelheber during a 1939 expedition, are printed on a mirror juxtaposed with images of rare stones in Katangese spirituality, reflecting the room with Josefa Ntjam, Otobong Nkanga and Sam Gilliam. The exhibition includes work by Otobong from the Kolanut series, questioning the consumption of natural resources, that bleed into the third room like sound bleeds from a distant party in a township to a house. There are also amazing works by my friends Euridice Zaituna Kala, and Marie Aime Fatouche who create a dialogue about the fragility of materiality and form, glass, metal and ceramic archives juxtaposed with Samson Kambalu’s wall drawing.

The fourth room is small and poignant. It captures pain, tragedy, and trauma and proposes many more perspectives, along with absolute resilience, which comes out in the brilliant works of Myriam Mihindou, Sara Sadik, and Dread Scott — yes another Flag — there are a lot of flags in the exhibition. Dread Scott, in a work banned by George Bush, invites the audience to walk on the flag and write how they feel about the American flag.

Lindiwe Mngxitama: I think that music holds the potential to dissolve the boundaries and constrictions of language, especially when we think of the politics of power implicated in naming and being named, from places of within and without. Here I think of Evie Shockley’s that’s a rap (sheet music for alphabet street:

if i sang the blues would that be new ? or knew ? would boos follow blues ? would blood follow, bud, flower, flow, ‘sang–froid’, cold-blooded, hot-blooded, male :: if i sang frigid would that be cool ? jazzy ? jizz, buzz, the word :: do i have the rite to write the body ? the right body to remain silent ? ‘habeas corpus’, to have the remains ‘dans mes mains’, my main man, handy man, unhand me, uncuff me, so i can speak in my sign(ifying) language :: signs, wonders, miracles, temptations :: three or four, tops:: hip hops micro-brouhahas, address em and from the mic :: ain’t nothing new son, about us being under the gun :: checked in the black box…

And her statement in her book Renegade Poetics: Black Aesthetics and Formal Innovation in African American Poetry, where she proposes that:

we think of not a black aesthetic’ or the Black Aesthetic, but of black aesthetics, plural: a multifarious, contingent, nondelimited complex of strategies that African American writers may use to negotiate gaps or conflicts between their artistic goals and the operation of race in the production, dissemination and reception of their writing.

Thinking about this beyond the borders of America, what does the sonic component you created for Globalisto. A Philosophy in Flux, offer to the exhibition and the things it is thinking through?

MO LAUDI: Music does dissolve boundaries, Amiri Baraka once said, “There are people who actually believe that politicians are more powerful than artists, what a bizarre lie.” I like to ask people to name one or two Jamaican Presidents, most people can not name any, I then like asking them to name a Jamaican musician and most name Bob Marley.

When sound is produced, when an object vibrates creating a pressure wave, this pressure wave causes particles in the surrounding medium to have vibrational motion. As the particles vibrate, they move particles close by, transmitting the sound further through the medium. What is the role of the artist if it’s not to make the revolution irresistible, to make hearts and minds vibrate to a higher frequency? The DJ performs a curated researched playlist transitioning bpm and harmonic tones, deconstructing a song, blending one song to another, to formulate a set that blurs the role of the musician vs that of the DJ as the role of the curator vs that of the artist. The vibrations set off by artists with their activism can transform a gallery, a church, into a space of resistance as the audience creates a vibrational motion in their community.

Arthur Jafa once said to me that music is the apogee of the African American experience, I say the African experience thinking also of the Diaspora. In the last room of the exhibition, he dedicates his work L.O.L.M to an American writer, musician, producer, a long-time critic for The Village Voice and friend, Greg Tate. Usually, AJ uses and assembles images found online as Marcel Duchamp would remix ready-made objects like a DJ to create one cohesive form with a unifying soundtrack. In this instance, the room is completely black the sound bleeds into the larger room where you have Raphael Barontini, Moshewaka Langa Porky Hefer Gerard Sekoto and an installation by myself titled Rest-ition (renaming the collection).who owns the past owns the future.

The installation interrogates the provenance of African artworks in western museums and points to the current debates about restitution. Migrant objects are isolated from their original cultural context, subject to colonial categorisation by western scholars. Variously acquired or donated, the MAMC+ has a collection of West African art composed of around 180 artworks or objects dating from the 19th to the 20th century. This collection is described in the catalogue of the MAMC+ as ‘Tribal Art’. This definition is now questioned in art, theory and in politics.

The sonic composition evokes spiritual restoration and healing, nature and freedom of movement — as the sound of the swift before it travels back from Europe to Africa — field sounds of the Black Atlantic calling upon the spirit of the ocean and of those lost in the ‘The Middle Passage’. The ceramic sculpture invokes the notion of a call for the restitution of land, resources and objects. I propose to open a debate with the MAMC+ about the renaming of this part of the collection in favour of less negatively loaded terminology that will incite new interest and research.

Lindiwe Mngxitama: How and why did you choose the artists and works that make up the show?

MO LAUDI: Friends I met on my travels, a little community.

Arthur Jafa did my music video in New York in 2010 when I was rapping with The Very Best, that was before he did Kanye West, Jay Z and Beyonce’s videos. I met Marie Aimee Fatouche at a party, we live in the same neighbourhood, Porky Hefer, and we just clicked. Lubaina Himid I met when I used to live in London I think, I’m not sure. I then met her again in Venice, she is good friends with Christine Eyene. I met Samson Kambalu through Ian Kier. I have been collaborating a lot with Sammy Baloji, he has a new show opening in Rome and Florence soon where I did the sound. Euridice Zaituna Kala and I have also collaborated, she was commissioned to make a body of work in relation to the photographer Marc Vaux, who documented the art scene in Montparnasse from the mid-1910s to the 1970s. His entire archive — prints and glass plates — are preserved at the Bibliothèque Kandinsky in Paris.

Researching this collection, Kala was dismayed to realise how few Black artists were photographed, even though it is widely known how influential they were throughout this period. This led her to title her response: Personal Archive: An Exercise on Emotional Archaeologies. Her work questions identity, representation and portraiture, while attempting to deal with her own sense of foreignness.

How is history transmitted? How do women get erased and made invisible even though they played important roles? Aïcha Goblet was a Black model and a muse to many artists. Here, all that remains is her exoticised profile wearing a turban. The mirror glaringly reflects us, the viewer. We are responsible for her story now.