In the entrance of Goodman Gallery Thabiso Sekgala’s Tiger, selected from his series Second Transition confronts visitors. The direct, firm gaze of the man photographed is softened by the fleece tiger beanie on his head, making him a figure that welcomes, but also introduces one to Sekgala’s thematic explorations of (in)visibility, ideas of home, belonging and dislocation.

Tiger, 2012

Bôna is the first solo exhibition of Sekgala’s work at the gallery since his passing in 2014, a show produced following consultation with the late photographers close family and friends. Works selected from his series Homelands (2009 – 2011), Second Transition (2012) and Running (2013) talk to each other across the gallery walls. The title is a Sesotho word, meaning “see” when used as a verb or “them” when used as a pronoun. The poignancy and potency of this title becomes clear viewed through Sekgala’s interests in how social borders create and are connected to visibility in society. His images force viewers to interrogate who is able to be seen and under what circumstances, and to think about how “them” is attached to those who are considered outside or relegated to the periphery, both in place and in dominant historical and contemporaneous narratives.

Sitting on koppie during the last days of the strike, Marikana

The curatorial interventions mirror the prompts put in place by the title and Sekgala’s photographic investigations. The placement of images such as Tsholofelo Moagie, Moletsie, former Bophuthatswana (2010) and Thembi Mathebula or Nzimande, Siyabuswa, former Kwandebele (2011) across from one another makes viewers aware of the added layer of seeing being created in the exhibition space – the people in the photographs looking at one another. As a viewer, one cuts the gazes in the works by moving in front of one image to view it in isolation. However, when absorbing works in pairs or groups one becomes aware of the various lines of sight present in the space.

Loding, former Kwandebele, 2010

Sekgala’s images of objects and landscapes without people have an eerie quality to them. Their stillness is jarring, and evokes an uncomfortable invocation of loss, displacement and searching for a sense of belonging. And yet, they also present themselves as props which people use to develop “place-related identities out of a notorious past” and develop “nostalgia for histories that could be considered illegitimate” (ideas expressed in an artist statement by Sekgala). This enables an imagining of self and groups in contested space.

“In photography, I am inspired by looking at human experience whether lived or imagined,” Sekgala once shared. “Images capture our history and who we are, our presence and our absence.”

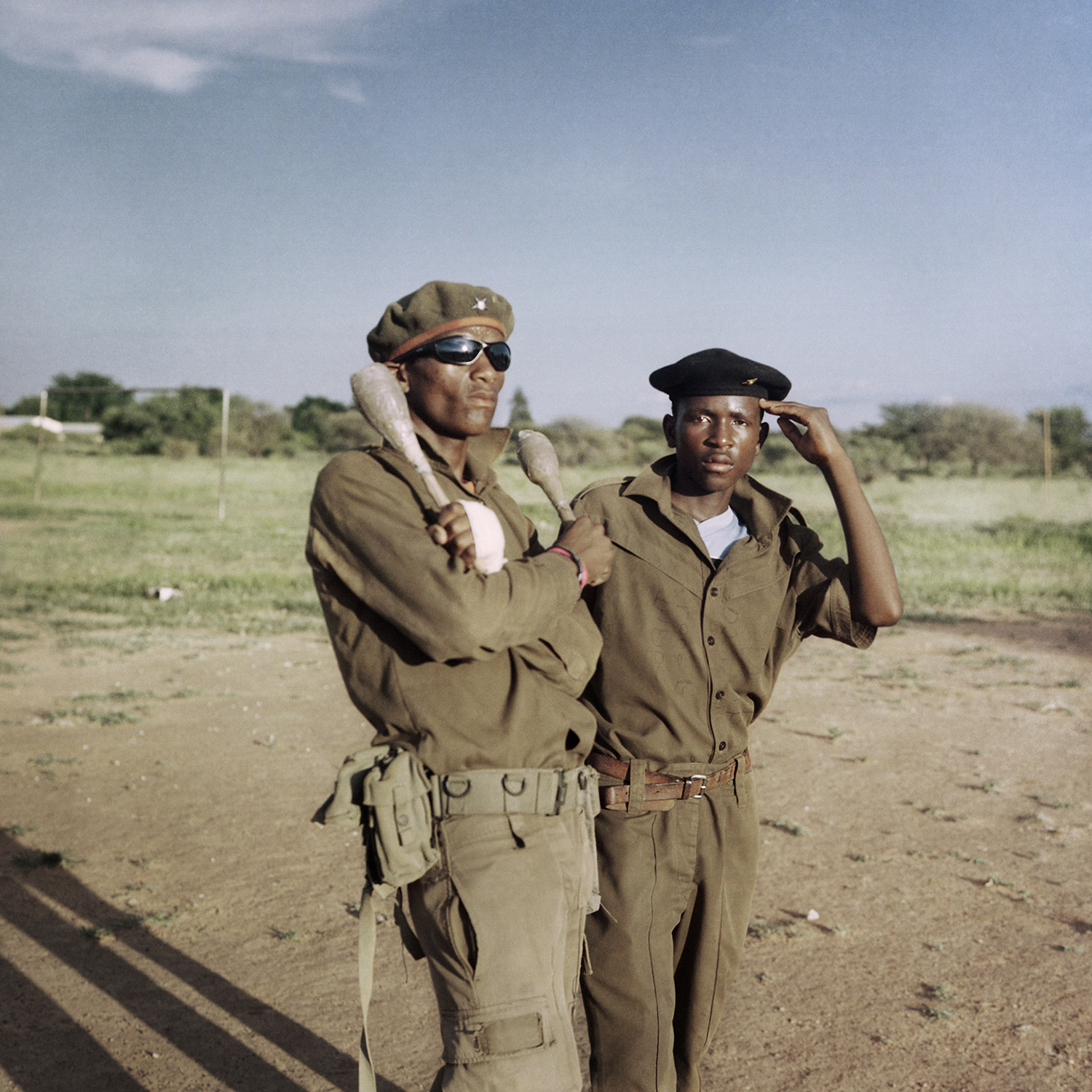

Second Transition 8, 2012

Installation photograph courtesy of Goodman Gallery