In their seminal book, Biennials, Triennials, and Documenta: The Exhibitions that Created Contemporary Art, Anthony Gardner and Charles Green trace the history of mega exhibitions and consider their impact on the art ecology.

Through this lens, they provide a reading of the “biennialization” of the art world. Gardner and Green argue that biennales have “brought clear benefits to art-history and art-making”, particularly by drawing “local practitioners into ostensibly globalised networks of art world attention and financial support.”

Alongside these benefits, of course, is the emergence of the star curator, star artist and star cultural practitioner that has left many wondering about the value of mega exhibitions in the first place. These shifts might be read as a hollowing out of art-making and its impact in the “real world”.

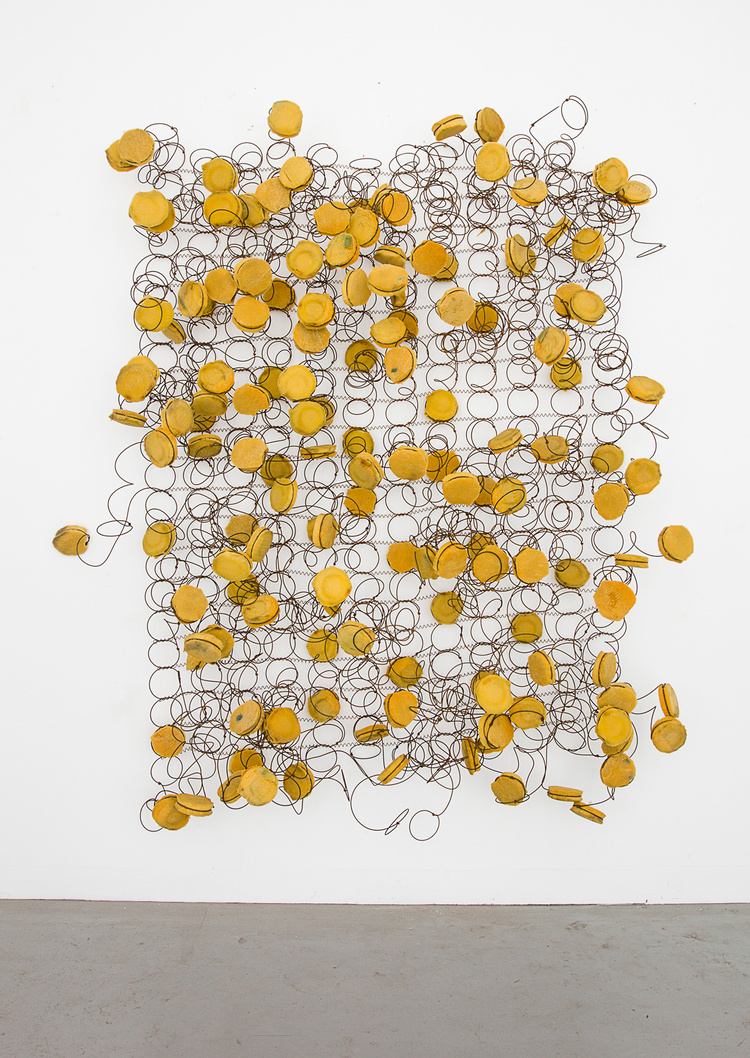

Bronwyn Katz, Droom boek; 2017.

Writing for Art reviewer, Martin Herbert, argues that “as art itself has gotten pointedly uglier, the eye-candy has instantiated itself in the makers”. It’s all about beautiful people at beautiful parties.

Herbert continues; “One thing you might forget about the art world when you don’t leave the house for a year is this: good looks and charm, plus the ability to throw a good party, have for some time been stepping-stones to artistic success.”

In his book, Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi, Geoff Dyer notes; ”Once you got to Venice….. you could be at a tremendous party, full of fun people, surrounded by beautiful women, booze flowing, totally happy – but part of you would be in a state of torment because there was another party to which you’d not been invited.”

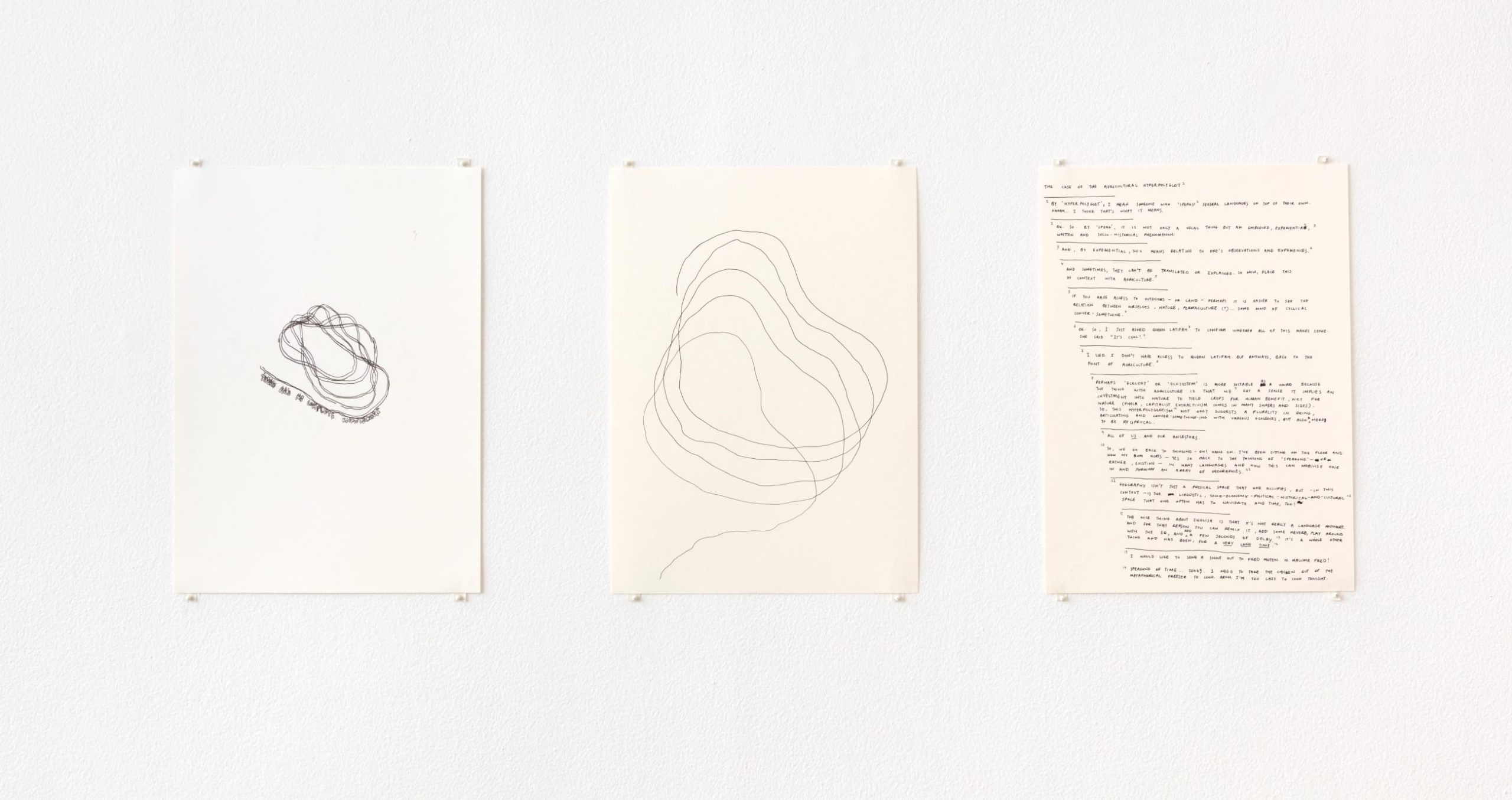

Simnikiwe Buhlungu, There Are No, There Are No Complete Knowledges, The Case of the Agricultural Hyperpolyglot; 2021.

All of these accounts point to the manner in which important art exhibitions have moved away from points of gathering where knowledge is produced, shared and contested, to places of socialisation, removed from the content the art practices seek to abstractly reflect on (migration, racism, representation, imperialism etc.).

All of this being said, we can’t completely disregard the biennale platform as it remains a possible way through which to create a bridge between the public and contemporary art.

This year, a few South African artists are participating in the 59th Venice Biennale — Igshaan Adams, Simnikiwe Buhlungu and Bronwyn Katz, alongside Roger Ballen, Lebohang Kganye, and Phumulani Ntuli who will represent the South African pavilion under the theme Into the Light. The curatorial concept is a recognition of the isolation and separation experienced through the pandemic and seeks to consider ways in which solitude impact creativity.

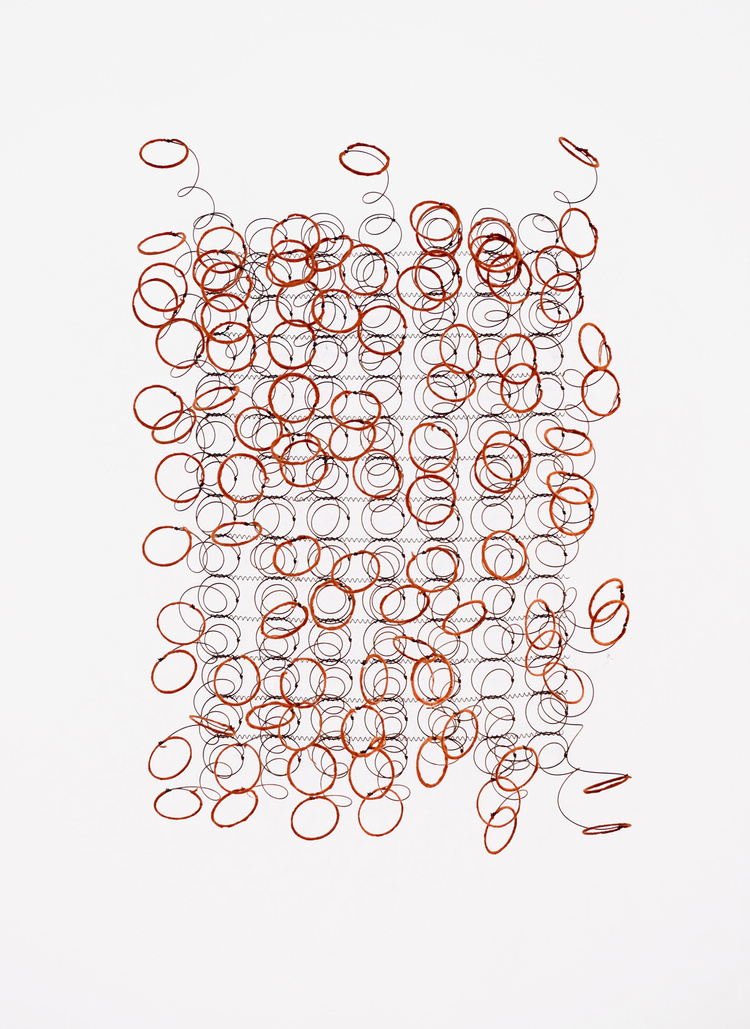

Bronwyn Katz, Rooi Spoor I; 2018.

It is exciting to see a cohort of artists with divergent practices as it offers an interesting perspective of the different aspects of the art landscape in South Africa. Adams is best known for his richly haptic tapestries that trace his own histories through material and form. He has exhibited at Kunsthalle Zurich in Switzerland and Hayward Gallery in London.

Recently, using film, sound and text, Buhlungu explores socio-historical phenomena and their nuances as part of a wider ecology. Buhlungu participated in the exhibition ‘My whole body changed into something else’ at Stevenson Gallery, where she presented a triptych of drawings as well as an audio installation.

Igshaan Adams, Govan Mbeki Road Khayelitsha; 2020.

Using photography, Kganye traces her personal history and through its documentation, offers a visual testimony of South Africa’s history. Earlier solo exhibitions include The Stories We Tell: Memory as Material, at George Bizos Gallery at the Apartheid Museum and Ke Lefa Laka at Market Photo Workshop, Johannesburg, South Africa in 2013.

Ntuli’s work merges artistic research, sculpture, video installations and performative practices. Recently, Ntuli presented Notes from an Algorithmic Memory, a performative project composed of a series of components and entry points of found moving images and sound through the 2022 ICA Live Art Festival. Ballen is a photographer whose career spans more than four decades.

He is best known for works that are often considered “strange and extreme” which seek to confront viewers to explore the deeper recesses of their minds.

Lebogang Kganye, film still collage from Dipuna tsa Kganya; 2021.

Lebohang Kganye, Pied Piper; nd.