Unearthing – a solo exhibition by Namibian artist Isabel Tueumuna Katjavivi. The walls of Goethe-Institut‘s exhibition space are systematically dotted with photographs, maps and text that reflect on the unresolved trauma present in Namibia today. This trauma is a build up from pre-colonial times, German colonial rule, the South African occupation and apartheid, the Namibian liberation struggle, and contemporary traumas post liberation. Isabel connects bodies, structures and land in her work, expressing that they are all containers of this trauma. Over the years, the land has witnessed and been victim to the fall of bodies and the categorisation of people, making it a memory bank. This is directly referred to in a second exhibition room– the floor is covered in sand. Plaster moulds of faces break through the stand, as if being uncovered through an archaeological expedition – Isabel’s expedition to delicately unearth her country’s painful memories.

I interviewed Isabel to find out more about her work.

How do you like to describe your aesthetic direction as an artist?

My aesthetic direction has changed over the years. Though my constant is the use of myself. I first started exploring with paint, moved along to camera work, and now explore more in tactile mediums – sand, clay. I think what says the most about my direction is the layers or imprints that I try to raise. My work is more than just the surface, and I speak about the layers that build upon one another to form our reality, and the imprints of our history that make us today.

How do you like to describe your thematic interests?

My interests derive from my personal experience and heritage. I don’t touch on a subject matter unless there is a connection there that allows me to speak from a place of truth. I cannot tell a story that I do not know or would never be able to understand.

I use my own form to explore these interests. The changing form of a woman, joy and pain, relationships between people. Now [I] look at relationships between the past and the present, and the lingering/long-term effect of Namibian colonial history, in particular the genocide. I wasn’t present during those times, but I fully am aware of the intergenerational trauma that lingers within me.

Please share more about your process when creating ‘Unearthing’?

Unearthing is the most recent work in a series of works. The journey began in 2017 with the deadline of the Bank Windhoek triennial (Namibia). I was already interested in the colonial history of Namibia, in particular the genocides that took place. I went on a journey to some of the areas where horrific events took place, deriving from that history. What surprised me most was that there were no graves or cemeteries (apart from those of the colonizers), and that there were no markings to indicate the significance of those sites/spaces. (I’m not saying that there needs to be, but there needs to be work done). From that point I made the past is not buried (2017) which was essentially a grave site of one body, that was partially buried and partially unearthed. This was my way of raising the question: where are our bodies? And signifying that this history, as an undealt with history, is buried but very much lingering in our present day. I took this further when I had to create a solo exhibition in 2018 – They tried to bury us. I created a floor installation of sand, grass and unfired clay faces. The audience was forced to step on the installation and forced to realize that this history has very present lingering effects on our present day independent nation. I had photographs accompany the installation. Landscape photographs of poisoned wells and trees that were used to hang people. I also had close ups of the sand, and the bark. This is where I started to look closer into the details of these weapons and the idea that these weapons – sand, trees (land) – hold memories of the history (and not just the people).

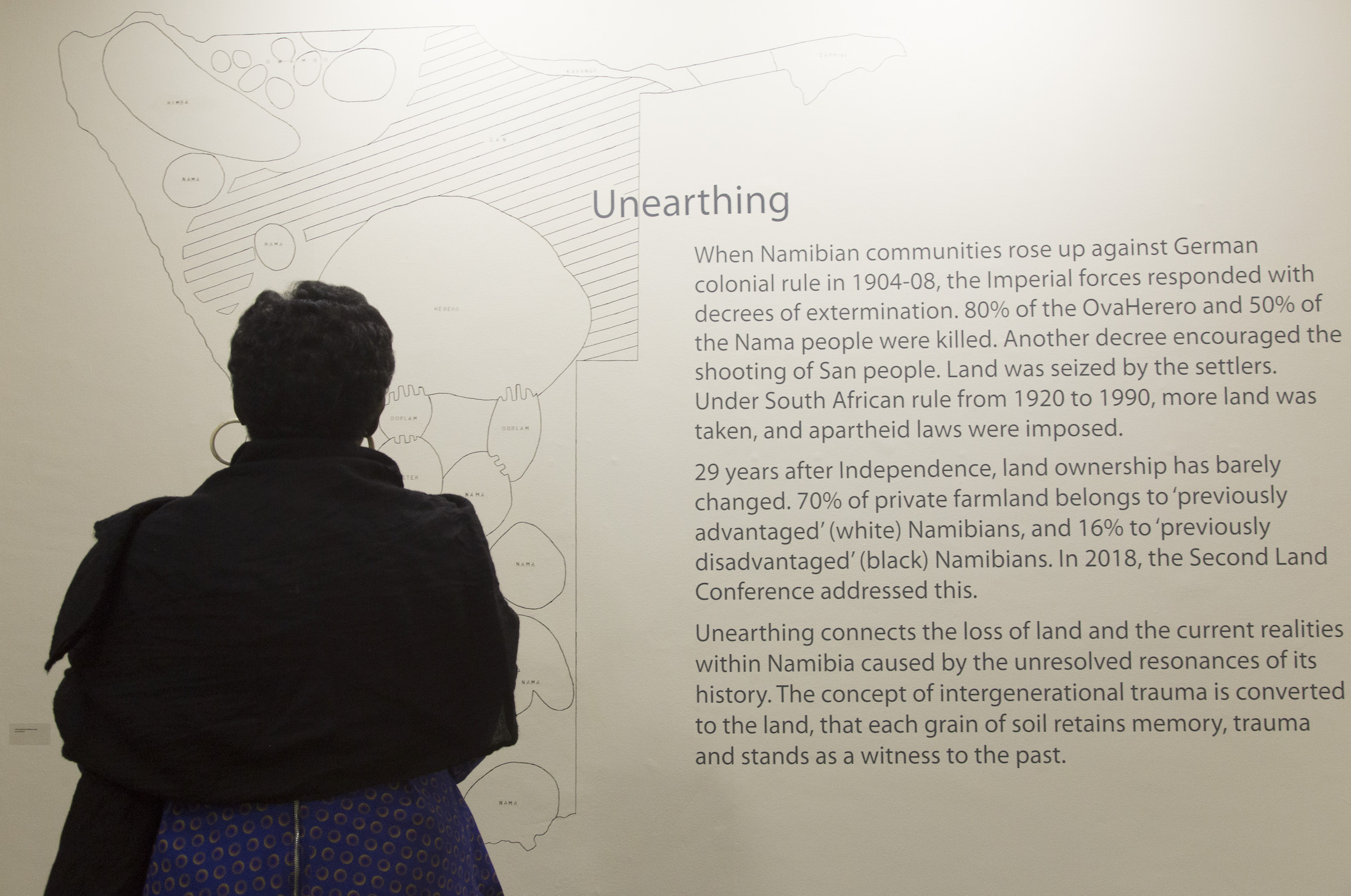

I was approached by MADEYOULOOK who were referred to my 2018 They tried to bury us exhibition, to be a part of their IZWE: Plant praxis series of exhibitions. My previous exhibition was my starting point, and we agreed to have a smaller version of the installation present – this is the room with the sand, grass, faces, extermination orders, and the wallpaper print of the poisoned wells. With the focus of the IZWE: Plant praxis being on the land, and with the fact that Namibia had recently (end of 2018) had its 2nd land conference, I turned to ownership of land and maps. I decided to add more close up photographs of sand to highlight the soil/land as an entity that holds memory. The maps I drew, which were all derived from sources, were to then show how the colonial history affects us today; the use of land, land ownership, etc. which of course has so many effects on people’s livelihoods today. All of these parts together unearth Namibia’s colonial history and show how it still lingers with us today.

‘Unearthing’ looks focused on the idea of how trauma is passed down through generations, and the idea that the environment observes and absorbs this trauma too. Can you please share more about these ideas, and your thinking around bringing this to life with the images and sand installation?

Without ever meeting my father’s parents, I had always been interested in my Namibian ancestors. I’ve heard a lot of stories of my father’s aunt and uncle’s grandmother, who survived the genocide. I’m very interested in memory and how it’s passed down to generations thereafter.

After going on my original journey to spaces where horrific events occurred (during the genocide/colonial period), I began to be interested in intergenerational memory, and the memory of spaces/sites of trauma. There is a lot of research by psychologists and geneticists showing that trauma is passed on from one generation to another. Site of trauma, is a term used by Logan and Reeves (2009) to describe places with scars of history that hold ‘the legacy of these painful periods: massacre and genocide sites, places related to prisoners of war, civil and political prisons…’ (p1).Hirsch (2008) explains postmemory as the ‘bodily, psychic, and affective impact of trauma and its aftermath’ (p.104), recalled from generation to generation and not only by witnesses to the trauma. By using postmemory theory, the research highlights the connection between the past and the present. Hirsch (2008) states that postmemory’s connection to the past is not actually mediated by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation. The artworks as essentially imaginative creations grounded in the visual and oral history research, so that they speak to the memories collected.

I realise that we as humans think a lot of the time about us and how things affect us; and when there is something we need to know or find out we often go and find others who might know more or go read books etc… We forget that the earth we are on has been very present through centuries of events.

Being in certain sites of trauma, for example the hanging tree (Ngauzepo) in Otjinene, you see people living right next to it. It is a tree that gives shade, but if you look closer and look at the layers of its bark you can just imagine the torment it went through, all last breaths it heard. I’m not trying to say that it feels etc., which it does as it is energy, but the point is that we overlook the earth around us that still stands (trees), or that we overlook as we walk on by (sand). There are stories of when digging to make foundations for houses, people would find bones in Otjinene and Swakopmund. The still visible sunken pits of the poisoned water holes.

There’s a quote that is in the exhibition that just speaks volumes to the idea that the land holds memory to the painful histories that occurred on it: Our people’s bones are lying like that at Kierikos. My grandfather told me, that vultures fed on the carcasses of the San people almost three months. (Erichsen, 2008, p34)

You also emphasize the idea that bodies and earth are containers of memories, and that through interrogation these memories can be revealed and offer avenues of remembrance. Can you please share more about this?

In Namibia, we don’t have a lot of monuments, structures to commemorate people or events that happened in the past. Those that we do are either made by one community or speak to one community, or made by foreigners. What all communities have though, are forms of commemoration.

A lot of Namibian history is not taught in schools, and rather passed down within families and communities. With this in mind, I think it is very important for us to interrogate our history and make it accessible. I think it is also very important to do this in a way that is inclusive. It is not about blaming one side, or playing victim, but rather allowing the voices of our ancestors to be heard, and to remember all. End of the day, all sides lost their ancestors.

I take a keen interest in the need to develop a Namibian remembrance language that is for all in Namibia.

What comes to mind are “Scars”. Scars on the landscape, on the collective and individual body, on the soul, on the nation. Scars may heal in that they are no longer bleeding, but they still leave a mark. Naming and remembering helps.

Your use of maps is incredibly powerful in communicating loss of land and the allocation of specific people to specific spaces. The lines also mimic trauma lines left after earthquakes and other natural disasters. Please share more about your decision to use maps in the way you have, and how they speak to the landscape and close up sand images displayed?

Growing up, maps were there to show you what land belongs to whom, and where to find specific birds and animals. There was never much interest in the people who lived within the lines; this is also seen in how ruler lines were just drawn. With Namibia’s 2nd land conference, held at the end of 2018, I was very interested to see the various maps throughout time of land ownership. When you see a map, it is usually of one specific time. We very rarely compare maps to see the changes. When I found various maps and placed them side by side the changes, and the connections to the colonial history, was so apparent. It is a universal tool that I could use to convey such an obvious connection. The maps show the overall picture of the lingering effects of Namibia’s history, and the close ups of the sand that holds the memories portray the layering of those memories.

I am very interested in maps, cartography. An idea is to further this interest and create a cartography of the colonial history and genocide (sites of trauma).

This exhibition forms part of art and curatorial collective MADEYOULOOK‘s ‘IZWE: Plant praxis’