Disney, everyones favourite creative giant is dearly beloved by many across the world. Looking at the history of their earlier representations, however, it is clear that they have a gloomy past. Questions of whether or not children should be allowed to watch old Disney films have resurfaced due to the network’s entire filmography being uploaded onto their online streaming site Disney Plus – with the multinational mass media and entertainment conglomerate recently deciding to add disclaimers to films which portray racist characters and cultural stereotypes. The disclaimer reads:

This program includes negative depictions and/or mistreatment of people or cultures. These stereotypes were wrong then and are wrong now. Rather than remove this content, we want to acknowledge its harmful impact, learn from it and spark conversation to create a more inclusive future together.

Some of the more explicit manifestations of Disney’s racism are present in the 1941 animation of Dumbo, represented through the crows which many believe portray racist caricatures of Black Americans. The lead crow is named Jim Crow; a reference to the racist segregation laws in the US. Dumbo also included a song called “Song of the Roustabouts“, in which Black characters sing lyrics such as “We slave until we’re almost dead / We’re happy-hearted roustabouts” and “Keep on working / Stop that shirking / Pull that rope, you hairy ape.” However, this is not the only racist song used in a Disney movie soundtrack. In The Aristocats (1970). the Siamese cat is depicted as a racist caricature singing “Shanghai, Hong Kong, Egg Foo Young. Fortune cookie always wrong,” in a way that represents being Asian from a white racist imaginary — accent to boot — while playing the piano with chopsticks. Similarly, in Lady and the Tramp (1955) the cats Si and Am are also represented as racist caricatures who allude to Asian stereotypes in their animations with slated eyes and harsh accents. The two’s very entrance onto the screen is even marked by the sound of a gong. They serve as an animated on-screen representation of Disney’s racist and orientalist ideologies created to represent an entire continent. Now, while a disclaimer that Disney is taking accountability for the violent ideologies perpetuated by their animated representations is appreciated, have things actually changed from their so called classics? The live-action remake of Aladdin (2019) is an example of how we must not forget the ideologies and discourses of the Global North forming the bedrock for Disney and the films they make.

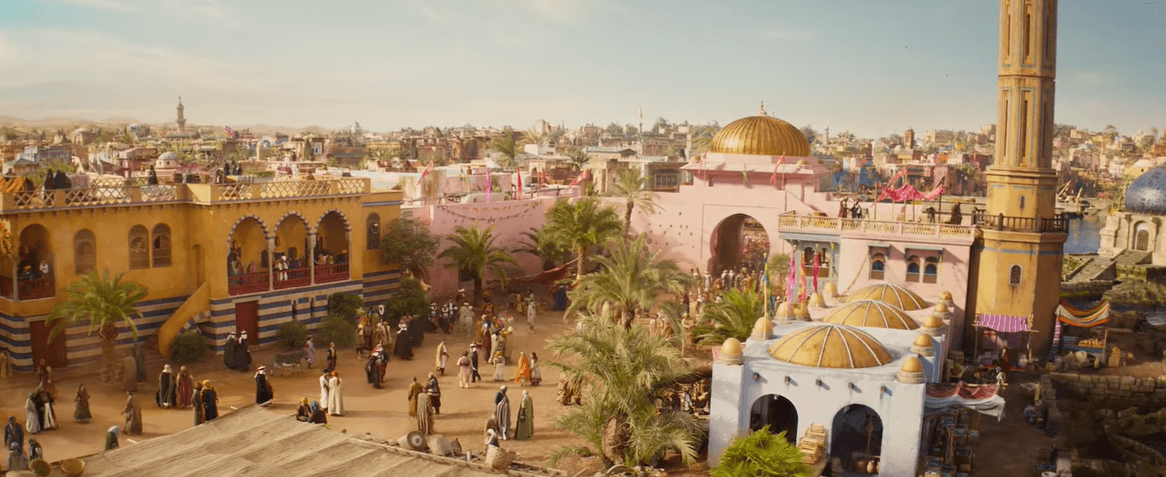

Aladdin is still almost as racist as its first telling, with a depiction of the stylised Global East all mixed together to create fictional Agrabah. A depiction that says more about how the Global North imagines the Middle East as opposed to the actual realities of the Middle East thus creating a melting pot of orientalist stereotypes. Princess Jasmine is given a narrative riddled with oppression that the Global North loves to impose on femmes from the Middle East, with Aladdin portraying her as controlled by her father. A type of sexist patriarchal control emphasised in the live action remake through the arranged marriage she is almost forced into with Jafar. Representation is important, however, it becomes a bitter pill to swallow and only does so much when these stories are mediated through a distorting/ distorted white lens. Not to mention that when Black and brown people are represented in Disney films, they tend to spend the majority of their on-screen-time transforming into varying forms, thus making them anything but Black and brown people. This is seen in Disney’s The Emperor’s New Groove (2000), where Incan ruler Kuzco learns humility after he’s turned into a llama by his evil advisor Yzma for the majority of the film. We see this again in Brother Bear (2003) which finds Inuit hunter Kenai turned into a bear to help him learn a moral lesson. The same thing is done to the only Black Disney princess in The Princess and The Frog (2009) when Princess Tiana and Prince Naveen are both turned into frogs for almost the entire movie. Similarly in Soul (2020) an animated Pixar (a Disney company) film where Joe Gardner — the lead Black character — is transformed into a teal mass, representative of his soul for most of the film.

“It feels like the characters seemingly have to be transfigured in some form for the writers and animators, mostly white men, to be able to truly care about them,” wrote Monique Jones for Shadow and Act. Adding “They aren’t allowed to learn and grow in their human forms, something white Disney characters are allowed to do.” The shocking thing is that these films are new in comparison to the earlier era of Disney animation. They were made in a time where writers should be acutely conscious of the politics and histories of representation, especially when writing stories of subjectivities outside of their own. So, when creating films that are targeted at the most impressionable of minds should we not try to aim for better representations? While these films now come with a viewing disclaimer on Disney Plus, little has actually changed in terms of Disney’s institutional practices and in the material space of the content they produce. The new Alladdin still paints an orientalist mirage and Soul still perpetuates (although implicitly) the dehumanisation of Black characters. While Disney’s original princess – Snow White – enjoys the greatest privilege of being the fairest of them all: to be seen as human, and represented humanely.