In the dystopian past of the national lockdown I, like many others, spent an unreasonable amount of time binging Netflix series trying to pass the long days in confinement. One of the most interesting and cringe-worthy shows I found myself unable to pause was Indian Matchmaking, a docu-reality series that follows Seema Taparia, better known as Seema Aunty — India’s top matchmaker, in her efforts to match Indian singles. From Aparna, who was criticised for being too fussy, as even Seema Aunty couldn’t find her a match, to Freudian single Akshay wanting to find a wife just like his mother, the show aimed to provide a look into one of the most intricate and well-oiled industries in India — the marriage industry. At the foundation of this industry, however, lies a bleak reality of what happens after many Indian wedding festivities have come and gone — abusive relationships and a misogynistic sense of ownership.

An anonymous Indian artist who identifies online as SmishDesigns creates art around these issues after ‘I do’. Smish’s first solo exhibition took place in Mumbai earlier this year, titled “Pati, Patni, Aur Woke” to channel what it means to be husband and wife in a woke era. The title is a play on the 1978 Bollywood film Pati Patni Aur Woh (the Husband, the Wife, and the Other). “This is an exhibition that delves into the many layers of marriage as an institution, and how women are disadvantaged within it,” says Smish in a Vice article. The artworks displayed in the exhibition stand in contrast to their backdrop of sections from the matrimonial classifieds, a section in Indian newspapers where advertisements seeking a suitable match are placed — many of which ask for a fair, educated, slim bride that is homely and innocent. This in itself serves as a reflection of the colourist ideas that remain in the Indian community. As I was not able to view the exhibition in person and came to know of it online it was easy to overlook the backdrop of advertisements, but once I noticed it I recalled seeing similar ads in newspapers such as the Lenesia Times here in Johannesburg and realised how marriage is thought of in India and how it’s thought of by South African Indians is not far removed. While Smish credits her inspiration to anecdotes from friends and family the work speaks to a larger audience and resonates with me here in South Africa. Growing up in the Indian community I, like Smish, remember hearing stories of the woes of marriage and bearing witness to a culture where a lot of the time the blame of marital mistakes falls on the wife.

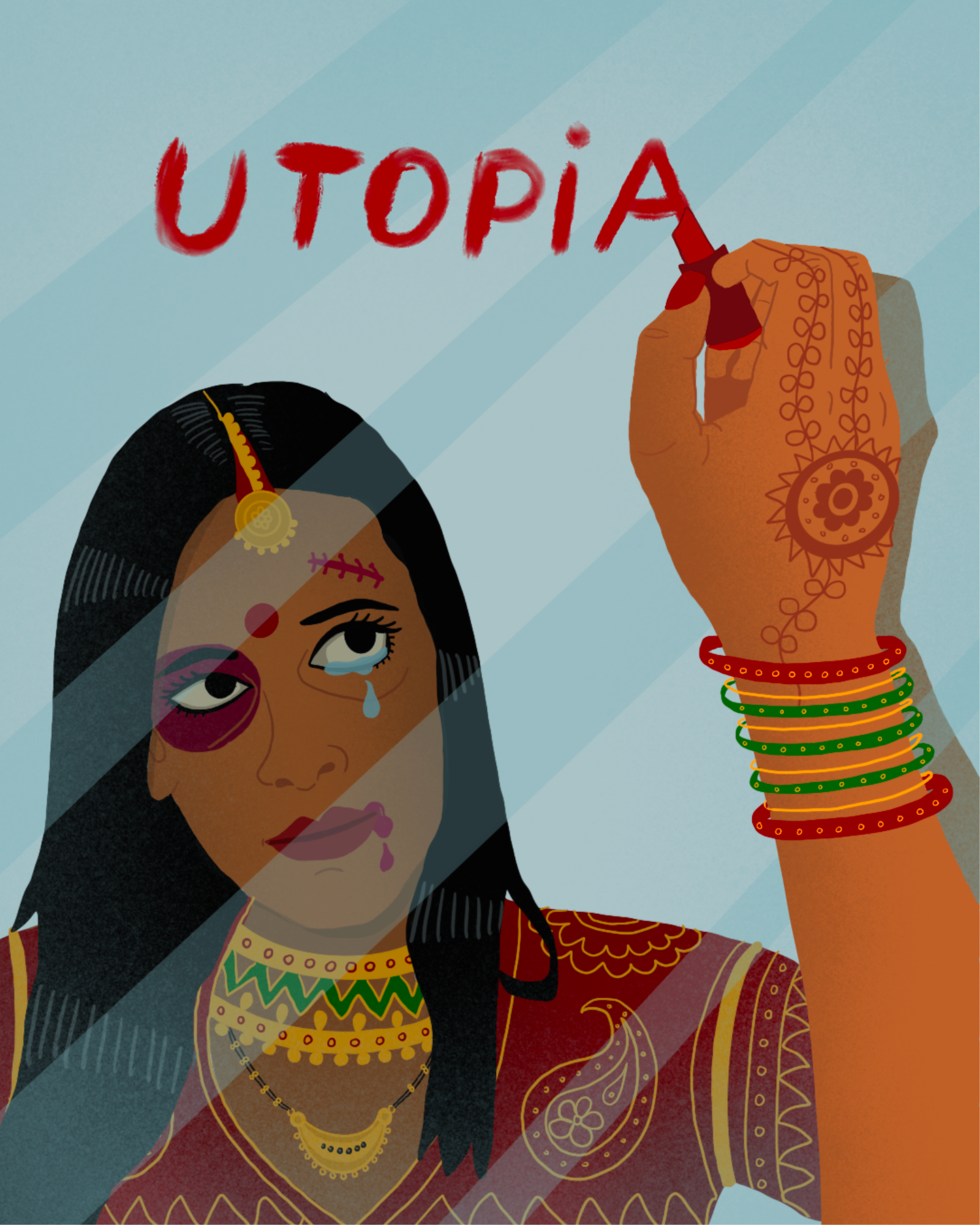

“In India, marriages are breaking like biscuits,” says our favourite matchmaker Seema Aunty a fact that rings true here as well, yet remains a fact that many people in the Indian community will brush over without facing the unfair realities of many Indian marriages. I am drawn to Smish’s work as they present these issues through well-illustrated artworks. One of which portrays a ‘Bride with dowry! Exclusive Sale in India’ well equipped with a microwave and pressure cooker that speaks not only to the objectification of the Indian bride but also is a reference to the dowry system in India. A system in which the family of the bride gives “gifts” or money to the groom and his family and which is now illegal but still sees for many dowry deaths— deaths of married women who are murdered or driven to suicide by continuous harassment and torture by their husbands and in-laws over a dispute about their dowry. Another work shows an Indian bride with a black eye painfully writing the word “UTOPIA” across a mirror in red lipstick—a reference to the increase in domestic violence Indian femmes have reported during the COVID-19 pandemic as lockdowns have caused femmes to be trapped within abusive households.

DOWRY BRIDE

UTOPIA

While many marriages are breaking, many aren’t allowed to as in Indian communities the institution of marriage is seen as a sacred bond allowing brides to find it hard to escape their abusive marriages. Particularly in India, marital laws do not see for the protection of femmes and they allow marital rape to be completely legal. Still, there are a few who are standing up against the intuition and when they do, they face enormous amounts of backlash and harassment, which is the reason why Smish remains anonymous. Smish explains that the ‘sanctity of marriage’ is a term abused by the judiciary of the country in India, used to silence married women and their struggles and is used with the same effect here. While South African law advocates well for women rights, Indian communities still value reputation over the well-being of women in abusive relationships. There is still an archaic belief among Indian communities that views divorced women as ‘damaged goods’ and pressures them to stay in bad marriages. Many women are expected to leave their jobs after getting married causing them to be reliant on their husbands and making it increasingly difficult to leave their abusive husbands, especially when the couple has kids, which many do due to pressure from their families.

IT’S A TRAP

NORMALIZE CONSENT