Cancel culture has gone from an inside joke starting on Black Twitter to a global movement that aims to hold public figures accountable for their actions. Cancel culture like many other movements does not come without debate, with those who are against it sharing their belief that we now live in a culture of snitching, offence-seeking and finger pointing which is causing intolerance on steroids. With varying opinions we ask: is cancel culture cancelled?

Cancel culture or being “cancelled” refers to the boycotting of a public figure once they say or do something that does not align with ideas of political rightness/social justice. We see “clicktivist” are advocating for the need of cancel culture in order to hold people accountable for what they say and do in the public eye and on social media. The argument against cancel culture is one fuelled by older generations criticising the movement as another example of this generation being “too soft” or “easily offended”, when the reality is that perhaps this generation has a better sense of social awareness and commitment to accountability. The use of social media is effective at calling attention to these offensive, problematic and violent behaviours thus in-turn creating consequences for the actions of those who were previously thought of as ‘untouchable’. Those previously protected by their status of power or privilege. In the past, public figures were sheltered by their privilege which also figured them as infallible and protected them from the kind of public scrutiny and accountability cancel culture evokes. Cancel culture has shown us how social media can be turned into a social tool used to change the ways in which power can be distributed and a means to call for those individuals with and in power to be held accountable for their actions.

Image sourced from Well + Good

While doing research in the debate against cancel culture, I read articles comparing cancel culture to a group of moms stalking their children’s pre-school teacher’s Facebook page trying to find hints of informality. While this sounds absurd, there was a point of agreement in their argument — perhaps the only point I agreed with — that cancel culture in nature seems as if it lurks and stalks and waits for you to mis-step and then pounces to cancel you. Although cancel culture on a base level seems to be a way of airing out the dirty laundry of public figures, it does cause us to think about how and why we let certain people carry this dirty laundry around for so long, constantly committing their offences with nobody speaking up against them. Cancel culture does tend to over simplify and view things in black and white, a binary in which certain actions receive the same amount of backlash as actions that are undeniably worse. Leading to a culture that views sexual assault on the same level as fake outrage online. An example of this would be the Taylor Swift vs Kim Kardashian and Kanye West drama in 2016 and how this caused the #TaylorSwiftIsOverParty in response to Kim Kardashian releasing a voice recording of a conversation between Swift and West. In the leaked recording, Swift seemingly gives West permission to use her name in his song “Famous” even though Swift expressed outrage after the songs release for the way in which it portrayed her. The backlash, boycott and bullying Swift received was astronomical. However, we see people like comedian Louis CK — who after being accused of sexual misconduct, and admitting that the accusations are true — still selling out shows after the fact.

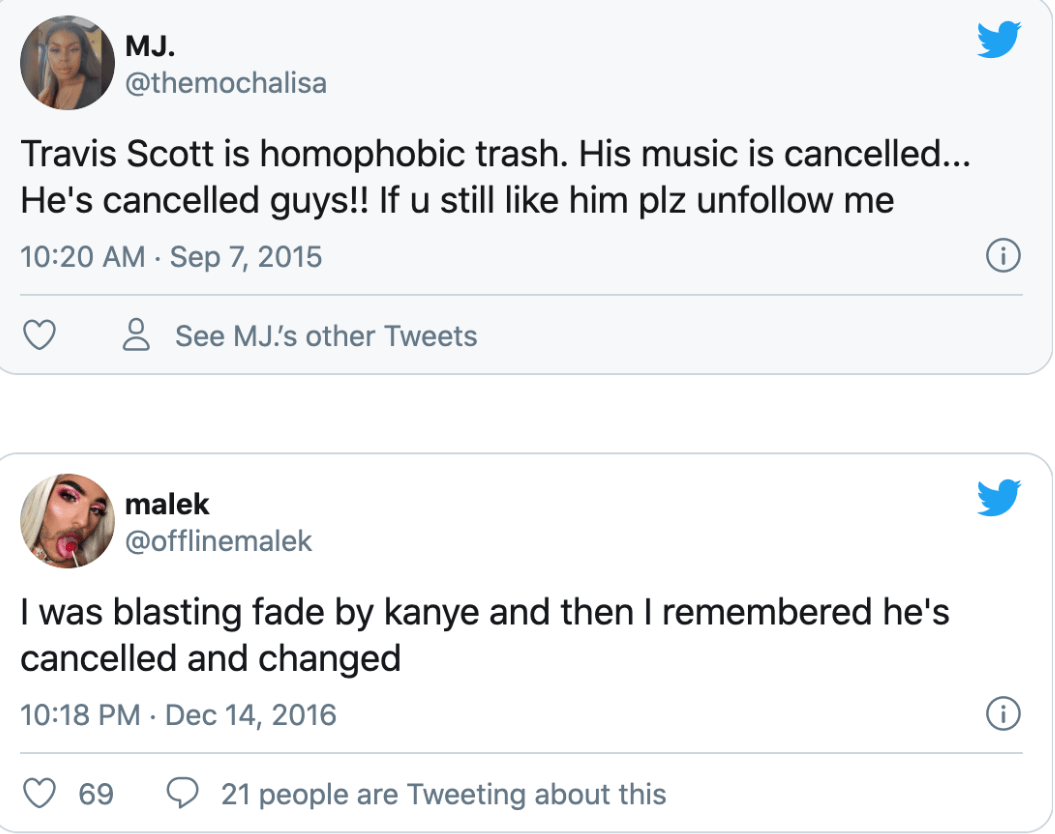

Screenshot image sourced from The Black Wall Street Times

This brings in another factor of the debate, thinking about if cancel culture is perpetuated by misogyny. While cancel culture seems to effectively work against women as seen in Swift’s case, men such as Michael Jackson and R Kelly saw for a rise in streams of their music, not a decrease, following controversial documentaries being released and them both being ”cancelled”. This continued support of people who have been cancelled shows that instead of leading to the boycott of someone, cancelling them can have an adverse effect and cause for sympathy and more support. Cancel culture only became an issue when it started cancelling everyones faves; usually men, usually white. Media outlets want to cancel cancel culture as they compare it to violent uprisings while others think of it as a movement against freedom of speech. The latter seen in “The Letter” published by Harper’s Magazine, in which 153 writers and public intellectuals warn that widespread cancellation is stopping the free exchange of ideas. However, the right to freedom of speech doesn’t give you the entitlement to hate speech. When we begin to think of cancel culture purely in terms of accountability — which is what it was intended to bring out of public figures — it is just a way of asking people in the public eye to address their problematic pasts and be held accountable for their actions. A means for restorative justice and the cancelling of cancel culture is being used as a way to avoid this accountability. Through cancel culture, we set up a system advocating that injustices are no longer going unnoticed and we are holding people accountable for their actions. Therefore, allowing us as a community to grow stronger as we show we are becoming less tolerant to racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic etc behaviours. If we continue to call out people on these behaviours, we cement a belief that systemic justice and equality are our non-negotiable.

Image sourced from internet archive

The main issue that many have with cancel culture is its willingness to seem unforgiving. Being cancelled is the social media equivalent of being trapped in a black hole with no way to escape and no sign of redemption on the metaphorical horizon. Cancel culture must not forget the ability for people to grow and change. However, when we think about the dangerous behaviours of some of the so-called-cancelled, it is hard to think of it as changing in the near or distant future. Should we invent a cancel culture scale which would judge the level of the offence committed and answer whether or not an action is forgivable. Cancel culture should move to an approach of thinking that behaviours need to be changed and that people themselves can seek redemption — it should move towards shaping itself around an abolitionist framework that centres those who have been done harm to, while also leaving possibility for restorative and redemptive justice. The cancelled can be uncancelled if they do the sincere work of changing their behaviours as well as apologising and actually putting in the effort to learn. Apologies matter and how one reacts when they are cancelled is important; when people are cancelled and they have a defensive reaction it shows an inability to change by not acknowledging the need for change itself.

Cancel culture should not be cancelled, but rather, reformed in its approach and ideological framework. Before cancel culture had a name, and before everyone’s faves were cancelled and the media noticed a pattern, there seemed to be no issue in calling for a boycott of a public figure in a call for them to be held accountable for their actions. Perhaps the word “cancel” itself is the issue — perhaps a signalling at the increasingly dogmatic and carceral relationship we are developing with rhetoric — with the word itself alluding to the end and our imaginations unwilling to do the work of engaged thinking. If we start changing it to accountability culture, would we be more successful in seeing the movement being truly realised instead of being weaponised? Or is there a new social rule that if you don’t have anything politically correct to say then rather just be quiet and face your front?