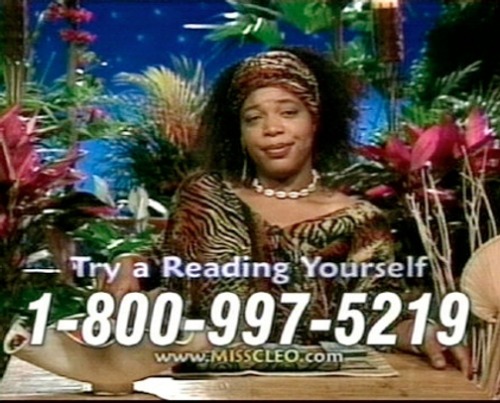

Siting inside the chair on any given weeknight was the infamous Miss Cleo. She looks like the 80’s black aunty of your dreams. On any given day, her outfit is an eclectic match of kente cloth tent dresses and silk scarves used to wrap up her thick black hair. She wears chunky jewellery made from brown beads, silver and cowry shells on every limb. There is no phone anywhere on the table in front of her. When people call in, it seems like they’re tapping into Miss Cleo’s universe from a different, less interesting realm. The service runs much like an agony aunt column in the paper, except with a mystic twist. People call in with regular folk problems like “I don’t know who the father of my baby is” or “where do you see my career going”. Miss Cleo straightens her back a little bit in her chair and in an accent that has a round trip ticket from Kingston to Compton says, “me a need ya birth date, babygirl”. It is this woman, Miss Cleo, who has become an overlooked part of the cloth that makes up today’s strange digital culture.

Television in the 90s was almost synonymous with the infomercial. Entire networks were dedicated to advertising bits that ran almost like short tv shows. People could shop while they watched, preview videos or access pay per view services. In the litter of infomercials, wrestling matches and kitchenware, there she was. Miss Cleo was the face of The Psychic Readers Network, a pay-per-call psychic service that dominated call waves in the 90s. Claiming to be a sort of Jamaican shaman, armed with ancient Obeah, Miss Cleo could be seen providing the truth-seeking and confused with the answers to their personal problems in your daily infomercials. After she responded to their existential woes, the camera would zoom directly onto her stern face as she shouted, “CALL ME!” And they did. The service was so popular that Miss Cleo appeared on radio and daytime television regularly, looking into the futures of audiences across America.

At the height of her popularity in the mid-90s, calls came in by the hundreds, daily, with people wanting to consult Miss Cleo personally. Instead, clients were redirected to low budget actors who performed ‘Miss Cleo’ to desperate clients. The company took a big hit in the late 90s when the government fined them for fraudulent practices. According to press documents, the Miss Cleo Service had billed people an estimated $1 billion USD through hotline numbers and credit cards. People had been billed for a service they thought was free, and most never spoke to Miss Cleo herself. As the company fell from Grace, Miss Cleo faded from public view. Saved are a couple of interviews: one where she came out as a lesbian and another where she revealed she was living in Toronto, the worlds most beloved spiritual scammer as largely faded from the public imagination.

The image is confusing. Miss Cleo read both as someone you know and a caricature of that person. The outfit was a nod to the Afrocentricity of the ‘80s. Her patois was awkward and passable. She didn’t baby her clients; in fact, she was often quite rough with them. But the roughness isn’t aggressive, it’s ‘tough love’. She slapped you upside the head and then kissed it better. She was the aunty on your block that saw who you were kissing under the streetlight and told your mother before you got home. She was the lady who sat in the front at church on Sunday while the congregation whispered that she might deal with spirits in her spare time. Miss Cleo was a character both incredibly relatable and incredibly curated. And she was exactly that, a character. An eclectic mishmash of personhood.

Miss Cleo’s time on the world stage is evidence that we don’t know what we’re doing – and we’re looking to black women for the answer. One could only imagine how powerful she would have been as an influencer in 2019. Miss Cleo is an interesting case study because her success bears similarity so much of what we see in popular culture today. Her success is at the intersection of the rise of the black woman and the rise of the scammer. Part of Miss Cleo’s appeal is in her black womanhood: she feels believable because, to a mainstream white audience, she is the ‘other’. The island woman who just knows. In a white world constantly searching for authenticity, story and experience, Miss Cleo feels like something to look at and something to listen to, for your own personal gain. At the same time, Miss Cleo was completely aware of her public deception. And we can only assume that she was okay with it; it fed her financial and theatrical needs. The dynamic between Miss Cleo and her crisis-ridden callers was a two-way dance.

The kind of spiritual/emotional scamming that defined the mid-90s hasn’t stopped. In the wake of Miss Cleo, the world at large continues to search for authenticity and community in black womanhood (and the performance of it). For instance, inspirational speaker and ‘spiritual teacher’ Iyanla Vanzant has created a career of guiding the misguided. On her TV show, Iyanla Fix My Life, her special brand of yelling-and-demeaning-before-healing has drawn guests from DMX to the Braxton Family. Like Miss Cleo, much of Vanzant’s appeal is in her black womanhood. She talks to you like she means it; she doesn’t mince her words. Her own hard life (Vanzant has been a victim of sexual and domestic abuse) serves as the paperweight that makes the advice she gives, stick. Her ‘no-nonsense’, harsh verbal code leaves her clients in tears, but is interpreted as ‘real love’. This specific brand of hard-knocks black womanhood leaves viewers feeling that they’ve witnessed an authentic journey to healing that they could never achieve in a shrink’s armchair. Vanzant’s TV therapy project feels communal in its informality and authentic in the execution of a persona that is completely outside of the norm of acceptability in traditional Western therapy.

The performance of persona and care is not limited to television. Early this month, self-care and support page @EmoBlackThot received hard-hitting backlash for performing black womanhood. The account, which had amassed almost 180k followers, created a digital self-care community around the owner’s fictitious identity as a queer, black woman. Thousands tuned in, daily, to be reminded to drink their water, stream Meghan thee Stallion and love themselves through discrimination, under the impression that they were listening to a black woman. The account also took money from followers (primarily black women) through digital cash-apps. When the account owner revealed themselves in Paper Magazine to be a cisgender man named Isiah Hickland, followers were shocked and betrayed, rightfully so. They had come to this account to share their personal stories, seek advice and find solace in someone who shared their struggle and their narratives and instead they were deceived.

What is most interesting about the @EmoBlackThot reveal is how these curated performances of black womanhood are so appealing to those outside of it. The desire to be in community with black women, to be a black woman and simultaneously exploit that privilege is so complex that it feels hard to understand. There is huge currency in black womanhood, especially in a digital era defined by the cultural products of black women. From the aesthetics that are most popular to the very way in which black women use social media as an outlet to talk about everything from structural racism to sex to healing journeys, black women have an integral hand in shaping popular culture. To be in community with this group, then, is to have authenticity. At the same time, the internet has provided limitless opportunities for people to scam and abuse. From big scams like destination festivals with Ja Rule to ones like Hicklands, the internet has provided the space for people to pretend to be anyone they want, facilitating the detriment of others for personal gain.

Iyanla Vanzant and @EmoBlackThot are by no means the same person, but they share a similar space in performance and exploitation. Both perform(ed) a particular type of black womanhood that is monetizable and applauded in the space in which it exists. In both cases, successful fanbases and careers were built off this community. Both Vanzant and @EmoBlackThot were able to become wealthy off using the stories and narratives of black women, particularly, framing themselves as the therapists to black women in need of help, without really helping them at all. The threads that connect figures like Vanzant and Isiah Hickland travel all the way back to Miss Cleo, the television psychic who was able to use her own black womanhood as currency in the game of helping people. In this game of digital connect-the-dot, Miss Cleo is an essential part of the story that traces the genre of black women’s giving advice in popular culture.