Morena boloka sechaba sa heso…

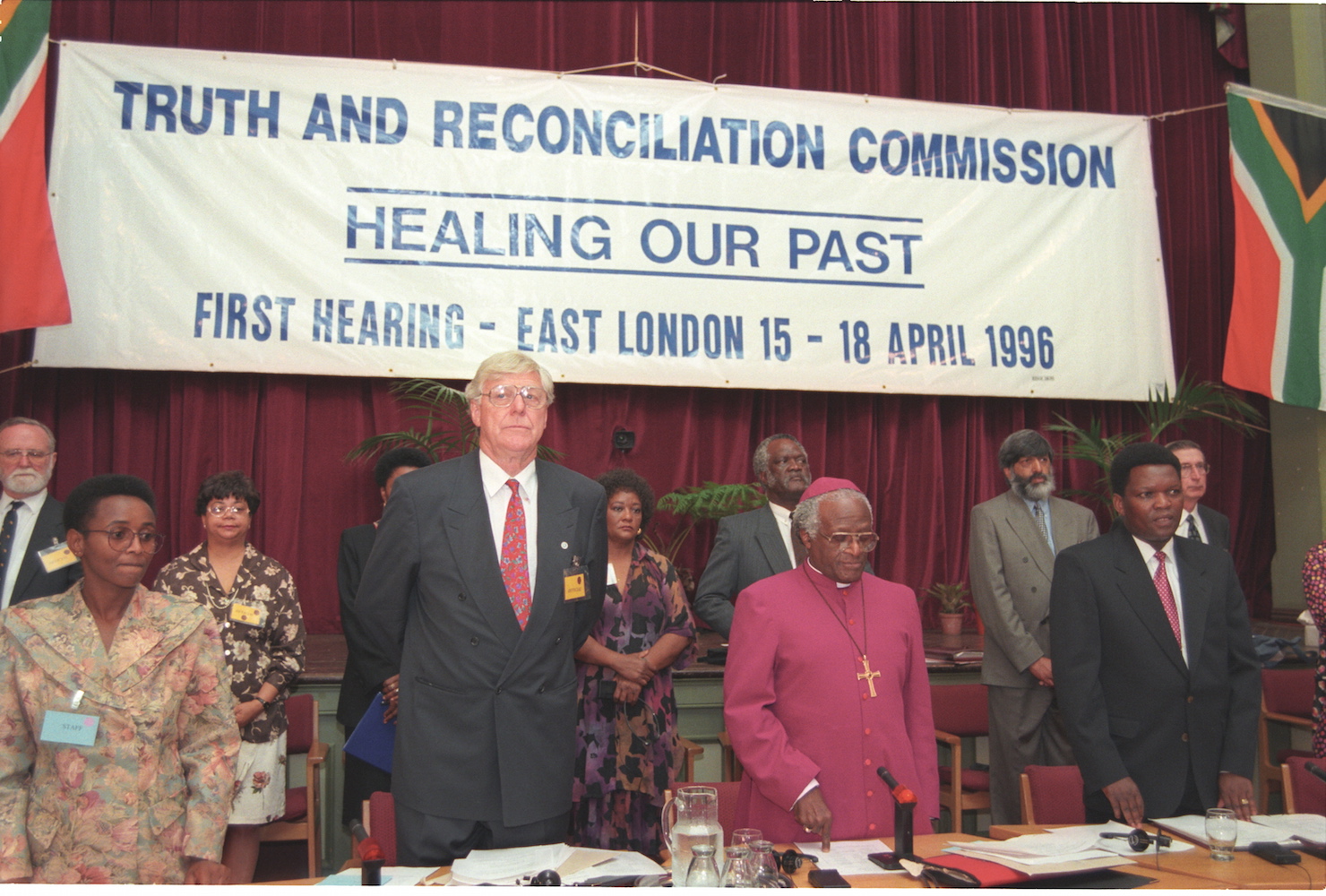

What a special yet haunted place South Africa is.

Thapelo ya Enoch Sontonga ents e le yona.

Vuyiswa Xekatwane, June 2022

“Why is it so abstract yet tangible at the same time and all encompassing?” (Julie Nxadi).

…

Interlude in muffled echoes from the Wake.

I had inherited her loss, ignorant of the improperly buried ghosts that made up parts of my melody’s orchestral choir. With time, I came to know that they were full of sadness and pain these ghosts of ours, full of hues of blues that spread out into oceans of forever loss.

It is difficult not to come to a knowing so deep of those etched onto the surface of my skin, deeply rooted in certain dark things beneath my flesh. Those whose scents move freely between my shadows and soul.

//

Still from Black Girl (1966) by Ousmane Sembène.

On the 6th of June 2022, Bubblegum Club writer Nkamoheleng Moshoeshoe wrote a piece titled Looking into the English language | South Africa, that engaged with English and its histories — as located within South Africa — as a site of ideology and identity making.

While reading it, many questions began percolating through my psyche, leaking disruption and recalibration into my memories and sites of identity making.

What gets unearthed when we begin to think of English and Englishness as a project?

What becomes revealed when we sit and smell through the stenches of histories we are radioactive with?

Morena boloka secaba sa heso.

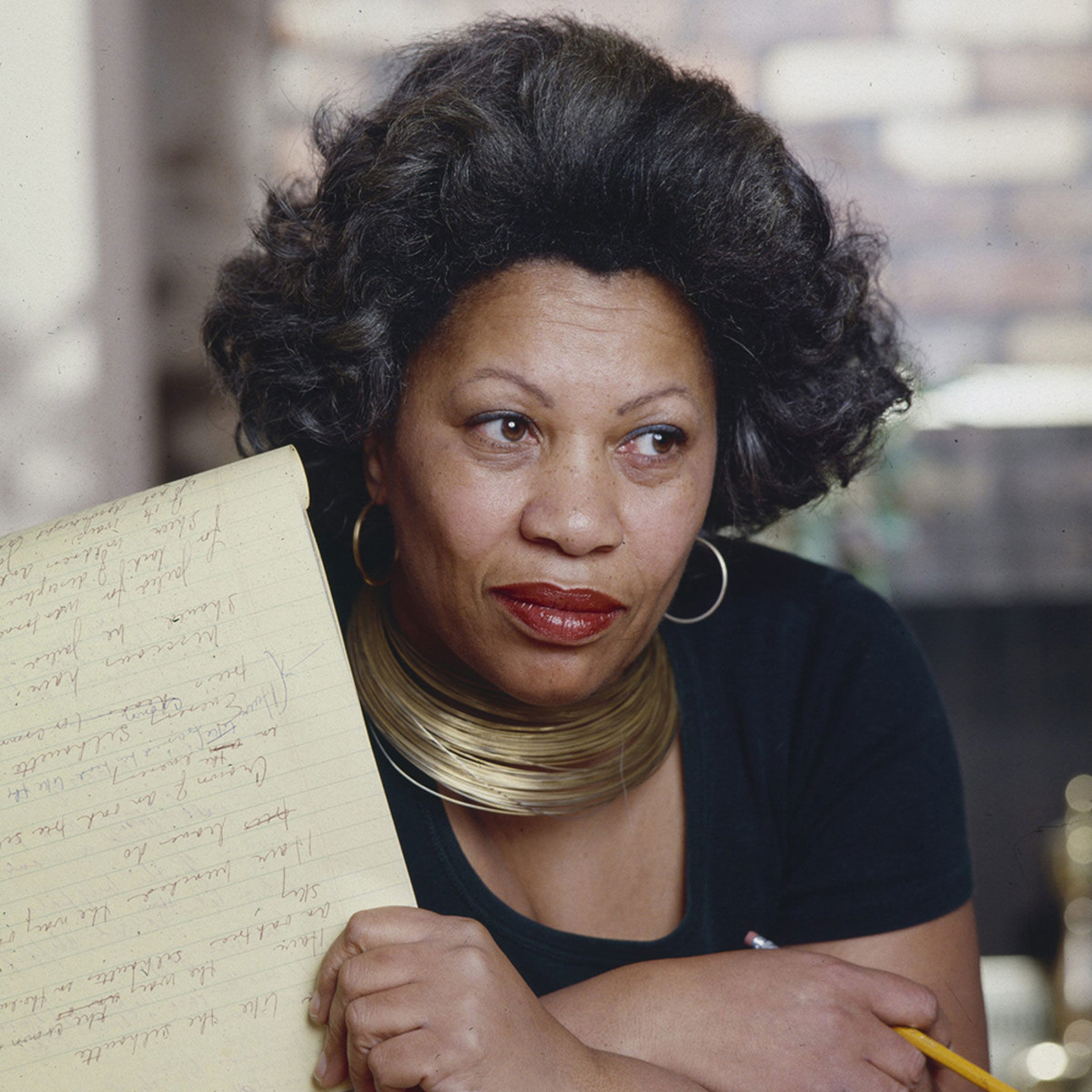

There is something about South Africa that reminds me, mournfully, of the little town thought up by the late Beloved Toni Morrison in her 1998 novel Paradise, the little town of Ruby.

A town built on the memory of the Old and the New Fathers where “the past is living rather than dead, and it lives in every wound that remains open in the present”, attached to a history that sought to categorise them on the hierarchy of humanity, in the negative. Not human, not worthy of paradise, not men.

And there’s something about being indigenous to this haunted land, South Africa — and having its history and ghosts thrust upon you — that reminds me of Ruby’s Black 8 rock residents whose wounds of shame and their Disallowing, have seeped into the sentence of their self articulation — forming the furrow of their brow.

Our Black Diamond Butterfly post TRC born free identities bound both to the history that produced them and reproach to the present which embodies that history.

Many of our country’s Black born free generation went to predominantly white and Model C schools, and that encounter — with whiteness and Englishness — seeped into the crevices of our relationship with our own Blackness, our ontological existence and the ways we inhabit our bodies.

We heard it one too many times, the shrill assertion from the teacher’s desk, violently placing you back into your little Black body and the implications of its presence in those mostly Lilly white class rooms: “this is not a shebeen” or “this is not a taxi rank” or “this is not a township, here we speak English.”

Utterances wrapping your body, your Blackness, your indigenous language in shame. Here, shame becomes a script, disseminating affective instructions that turn you away from yourself.

In States of Injury: Power and Freedom in Late Modernity (1995), Wendy Brown makes the assertion that, “subaltern subjects become invested in the wound, such that the wound comes to stand for identity itself. The political claims become claims of injury against something or somebody… as a reaction or negation.”

Following Brown’s theory of subaltern subjectivity and identity forged by virtue of wounded attachments, one could argue that the founding of our Black born free identities cannot be removed from the memory of the pain and violence of being wronged.

The transformation of the wound into an identity cuts the wound off from a history of ‘getting hurt’ or injured. It turns the wound into something that simply ‘is’ rather than something that happened in time and space.

I think of a conversation between writer Julie Nxadi, Designer Keenan Oliver and Director Mzonke Maloney on a podcast episode called A Cup of Tea with Julie Nxadi:

The English then comes to represent Englishness right? And its presence becomes a presence, it becomes another character. I don’t ever want to forget! That I went to these schools and I was traumatised, people act like it was easy learning English.

It feels like bits of you are being stripped away and then you start inhaling all of this new information.

And it’s constantly happening! You’re speaking your language and a white woman is chiming in telling you that you’re not allowed to speak it — and you feel these moments. You may suppress them during that time, kodwa those things are affecting how you’re dealing with, firstly, this English and xa ufik’endlini, how you’re dealing with this other language.

Still from Black Girl (1966) by Ousmane Sembène.

I don’t know what the work of holding English, Englishness and its lingering stench accountable looks unfolds nor do I know what breathing life into the ontological, spiritual and metaphysical absences ushered in my its presence looks like.

What I do know or rather, what I can feel, is that this is a choking umbilical cord and I think that we’re somewhere closer to a beginning than ever before.

What a special yet haunted place South Africa is.

Thapelo ya Enoch Sontonga ents e le yona.

Author of Paradise, the Late Toni Morrison.

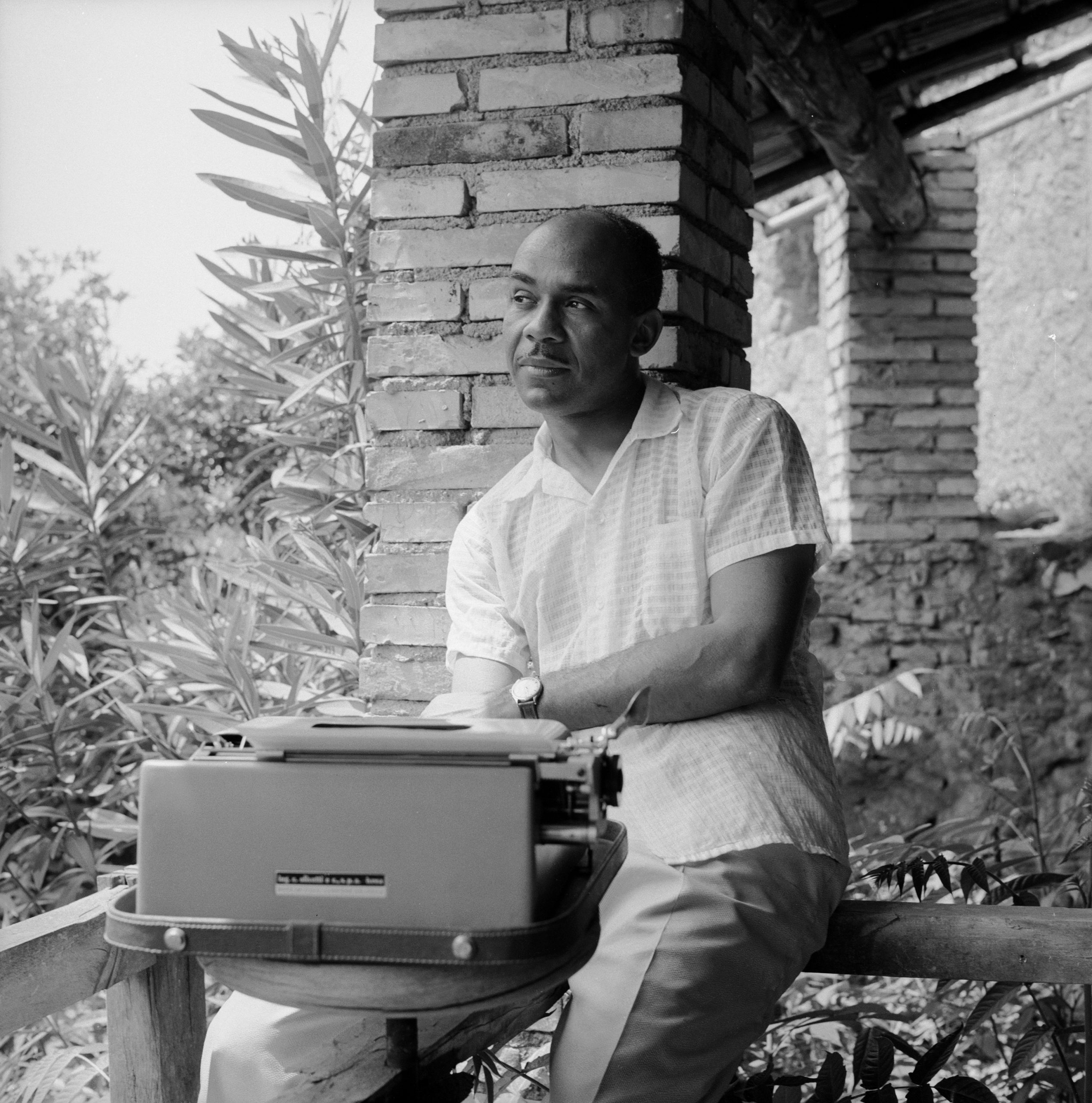

Author of Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison in 1957.