“But what you don’t know—is that that sweater is not just blue, it’s not turquoise, it’s not lapis, it’s actually cerulean,” begins one of the most iconic defences of the fashion industry, from Meryl Streep’s character, Miranda Priestley, in 2006’s The Devil Wears Prada. More than a decade later, almost any fashion student, designer or enthusiast will cite that monologue which encapsulated how the fashion ecosystem is a considered collection of efforts, time and money that the self-important and serious have deemed at best; frivolous and mindless and at worst; harmful and narcissistic. Historically, fashion has been continually looked down upon and much of the negative rhetoric around the fashion industry cannot be separated from the fact that the industry has been so tied to femininity and notions of ‘unskilled’ labour for so long. The cerulean blue monologue is part of a long, intensive combination of efforts from the fashion industry to prove that the culmination of magazines, textiles and events are more than just exercises in vanity, wastefulness and consumption but instead that fashion is art.

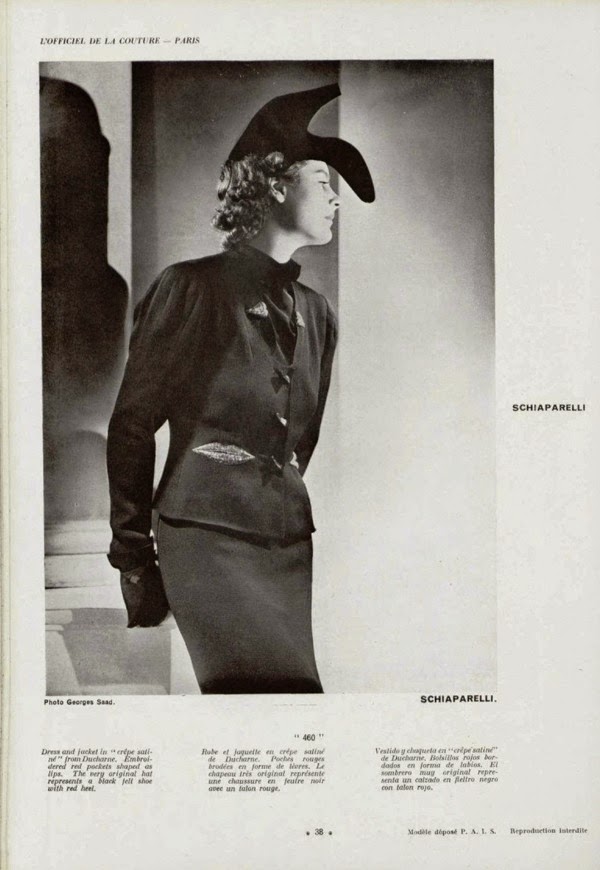

Shoe hat by Schiaparelli

Except is fashion actually art? Are designers, illustrators and sewists actually artists and not artisans? And what is it about ‘art’ that imbues respect and importance to the industry? As a long time fashion enthusiast myself, I had been previously inclined to say yes, fashion is art. There have been so many collisions between fashion and art for them to not be the same thing. In the 1930s, Italian fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli collaborated with Surrealist artist Salvador Dali on several creations, most notable being the Shoe Hat and Skeleton Dress in 1937. These creations took the form of a high heel shoe shaped hat and an evening dress with strategically placed and shaped padding to imitate the human skeleton. In the following decade, Andy Warhol and the Pop Artists would later make use of comic books, advertisements and everyday mass produced objects like Warhol’s famous soup cans to challenge and broaden the idea of what was and wasn’t considered fine art. This set further precedent for the idea that clothing could now also be considered art. In the 1990s, Lee McQueen would host confrontational, galvanising displays of his designs with breaking glass displays, models covered in tampons and robots spray painting dresses that would elevate the fashion show from a live catalogue to performance art.

Dior Paris Exhibition (2017)

However, the fashion industry is made up of more than just designers, creative directors, curators, photographers and magazine editors. When we speak of the artistic nature of fashion, we often omit how much of the fashion industry is the labourers. The sewists and garment factory workers, the sales people and the textile farmers provide the heavy lifting of carrying the fashion industry, yet, they don’t get called artists or creators. Adding on to that, the majority of these labourers are underpaid and overworked women. The distinction of fashion as art seems to serve to further the misogynistic and racist exclusivity of the fashion industry. Queen Victoria’s favourite couturier; Charles Frederick Worth of the House of Worth, is often seen as responsible for pioneering the idea of the fashion designer. Before Worth, much of dressmaking was the purview of lower to middle class women. They were unnamed, unknown and uncredited. Worth introduced the clothing label in the same vein that artists added their signature to paintings. He would “get inspiration” from artworks in the National Gallery and instead of toiling behind a sewing machine, he dictated his ‘vision’ to seamstresses. Following Worth, the fashion designer was no longer a labourer but a conceptualist, a thinker, a philosopher. All while gaining this greater success off of the contributions of women, Black people and NBPOC.

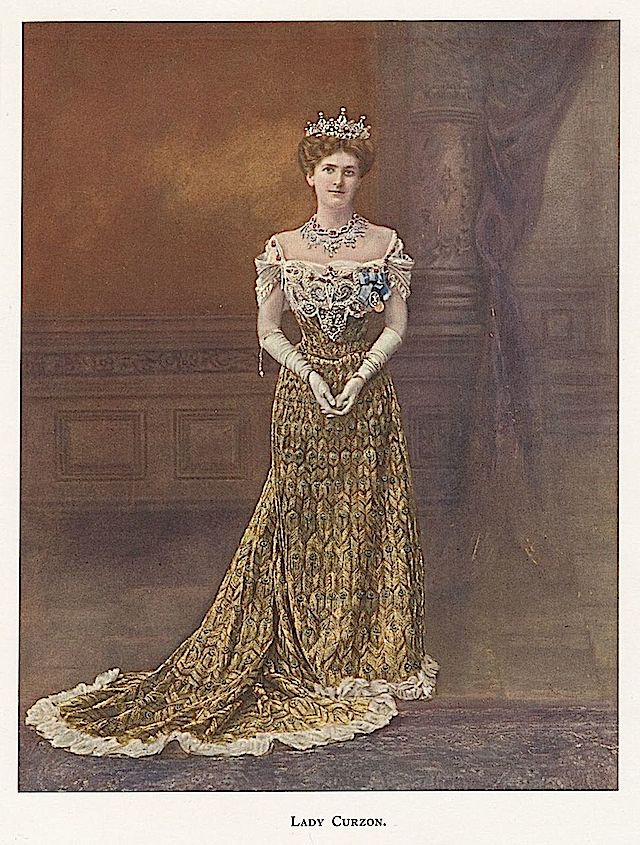

Lady Curzon’s 1903 Worth peacock gown

House of Worth gowns were—and still are today—breathtaking and elaborate creations that deserved to be celebrated and preserved for their beauty and craftsmanship. Dress historian, Cathy Hay has spent years in the making attempting to recreate one of Worth’s most elaborate gowns, the peacock dress which was commissioned for Lady Curzon in 1903 for the coronation of King Edward VII. The dress features special gold wire weaving embroidery on panels of silk taffeta, completed by Indian embroiderers in Delhi. This special style of embroidery, called zardoni, is unique to Indian craftsmen and when Hay had attempted to recreate it in the Western needle-and-thread style—she had calculated that it would take her 30 years to complete. Yet, the specific Indian craftsmen involved in the process of creating the dress are listed as “unnamed” in the museum displays of the dress while Worth’s receives engraving. The dress itself is an extension of white supremacy—not only because it was made to celebrate British occupation in India but also because it erases the contributions of the Indian individuals involved in its making, in order to prop up the white man.

Lady Curzon’s 1903 Worth peacock gown (detail)

This idea of fashion as art is also used to excuse fashion’s other crimes such as cultural appropriation and body dysmorphia. As if it’s OK to treat indigenous peoples’ clothing as costumes because “it’s art” or the fact that the designer’s vision can only work on the thinnest of models. Furthermore, much of the fashion equals art rhetoric only exists to advance the commercial nature of fashion. The prestige of a museum display or a Vanessa Beecroft endorsement helps satisfy fashion’s bottom line. It also works insidiously in the best interests of the industry to call itself art, so that it can get away with charging tens of thousands of dollars for garments while still underpaying and not crediting labourers. A gallery exhibition is just clever visual merchandising by another name. Of course, none of this is to say that fine art itself is perfect and without its own commercial, exclusionary, misogynistic or racist practices. In fact, there may be much to say about how the art world depends on those practices to survive in the way it does today. From that point, we should stop trying to make fashion art because art isn’t all that great either. And in our attempts to legitimise the industry we need to ask ourselves what already wasn’t legitimate about it? Women labourers aren’t frivolous, artisans and craftsmanship isn’t unimportant or unskilled labour and it shouldn’t take white men standing up to making something worthy.