Many of my articles surrounding the ever-growing world of analogue photography start the same. A simple introduction that states the name, age and base from which said artist works. A customary introduction of sorts to give you, the reader, the bare minimum set of particulars to at least have a name mulling around your mind as I go into detail about my thoughts and feelings surrounding their work.

With regards to Fynn Wilson, this simply would not be enough. Now art is often a way for artists and those interpreting it to make sense of the world — a connection to or the creation of a new reality. For 22-year-old Fynn, however, the visual language he has incorporated in his work takes this mostly mental exercise into something more fully rounded. A physical sense of self-exploration, understanding and care.

Every artist across the multitude of mediums adopted has their own personal motivations behind why they create, and I guess far less touched on are the questions surrounding just who they are and who they are creating for. Whether it be for consumption on a mass or micro level or, as is the case within Fynn’s work, profoundly personal exploration and piecing together of self. It may be detached, rooted in fantasy or the longing to create something new and better in an increasingly mentally taxing world, or as you may gather from Fynn’s own words, a cathartic release.

I think it’s important for photographers to come to terms with their underlying motivations for how they photograph if they feel so inclined. While studying at UCT, an old film tutor of mine told me that I sometimes tend to write in a manner which is a little too earnest, so I’ll try and keep this answer balanced for my own sake. Although I started photographing well before I was diagnosed, I think photography has always been my own way of coping with the demands of reality. When I was 17, I was told I had something called “DPD”, or Depersonalisation disorder, and that not much could really be done about it. DPD is quite common amongst people with PTSD and other stress-related disorders, and it presents in [people] a feeling of being totally disconnected from the world.

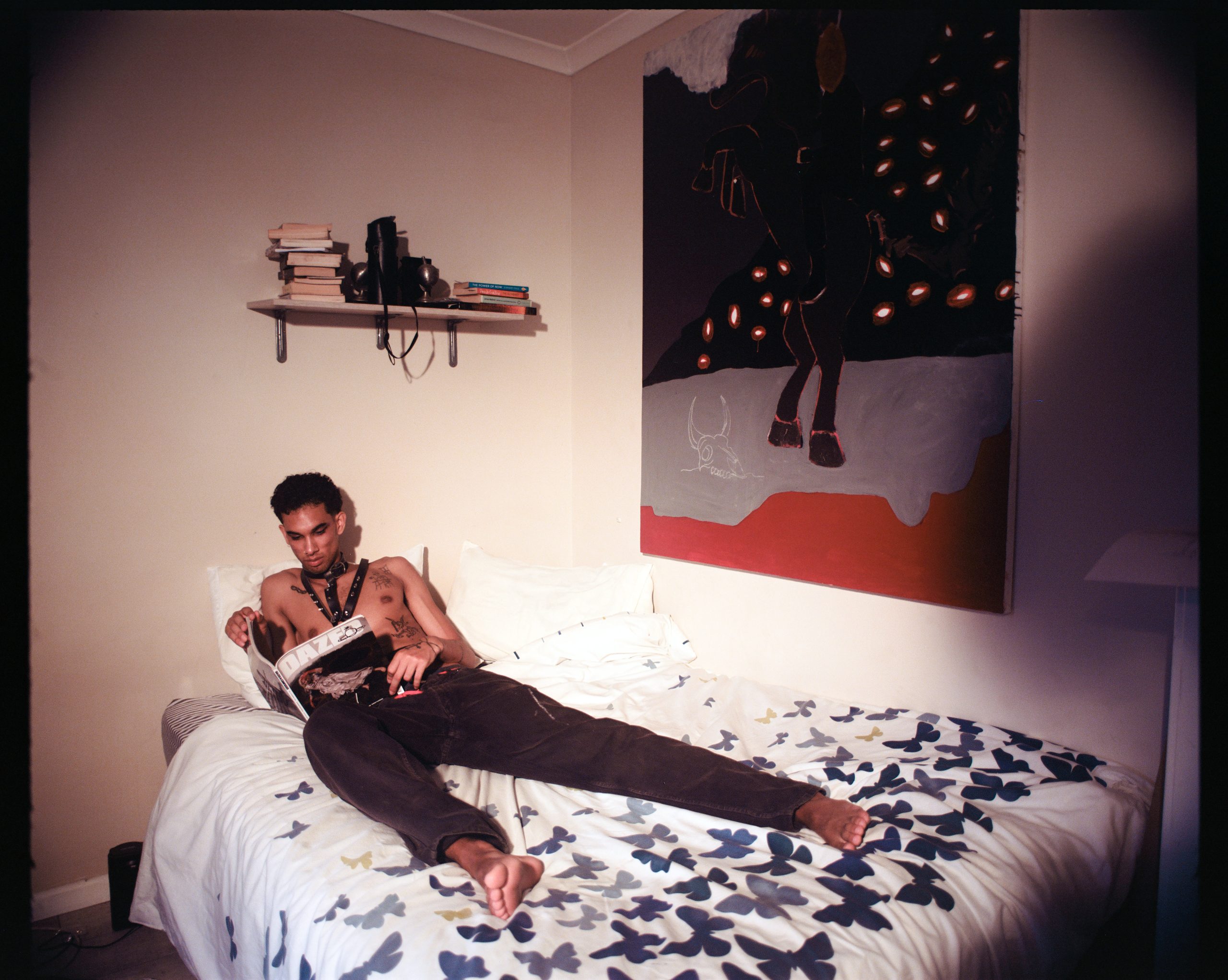

I often feel like my hands aren’t mine or the world I’m perceiving is a movie where people are on a stage, and things aren’t real, despite the fact that I know they are. Quite desperately, then, around the time I was diagnosed, I picked up my camera again. The difference this time, though, was that I was doing it to piece myself together. I did this quite intentionally in one of my most recent projects, ‘Whispers and Counting’, which a lot of the images you’ll see in this article belong. I guess the style is less of a creative direction than an intentional decision to come to understand myself better, then.

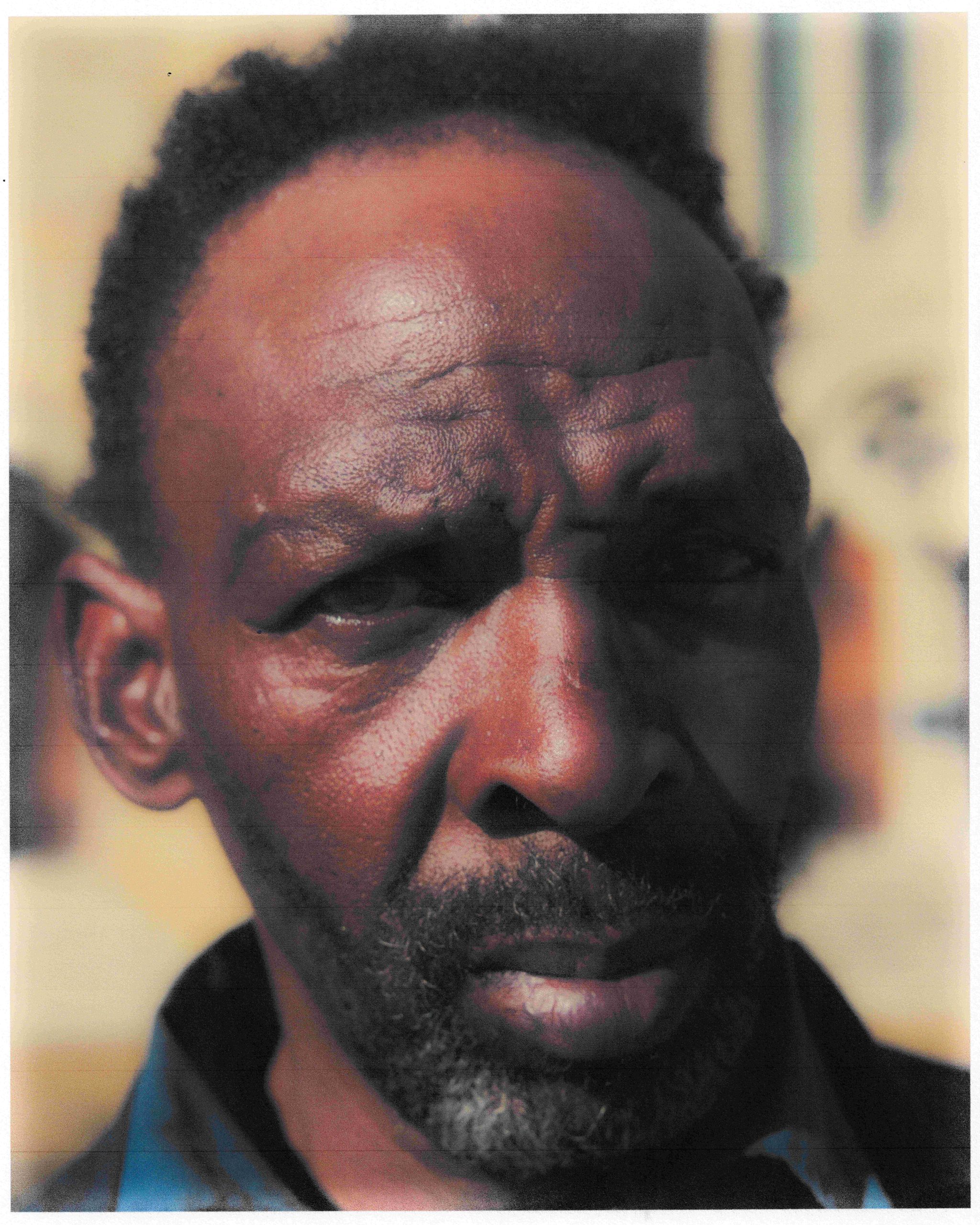

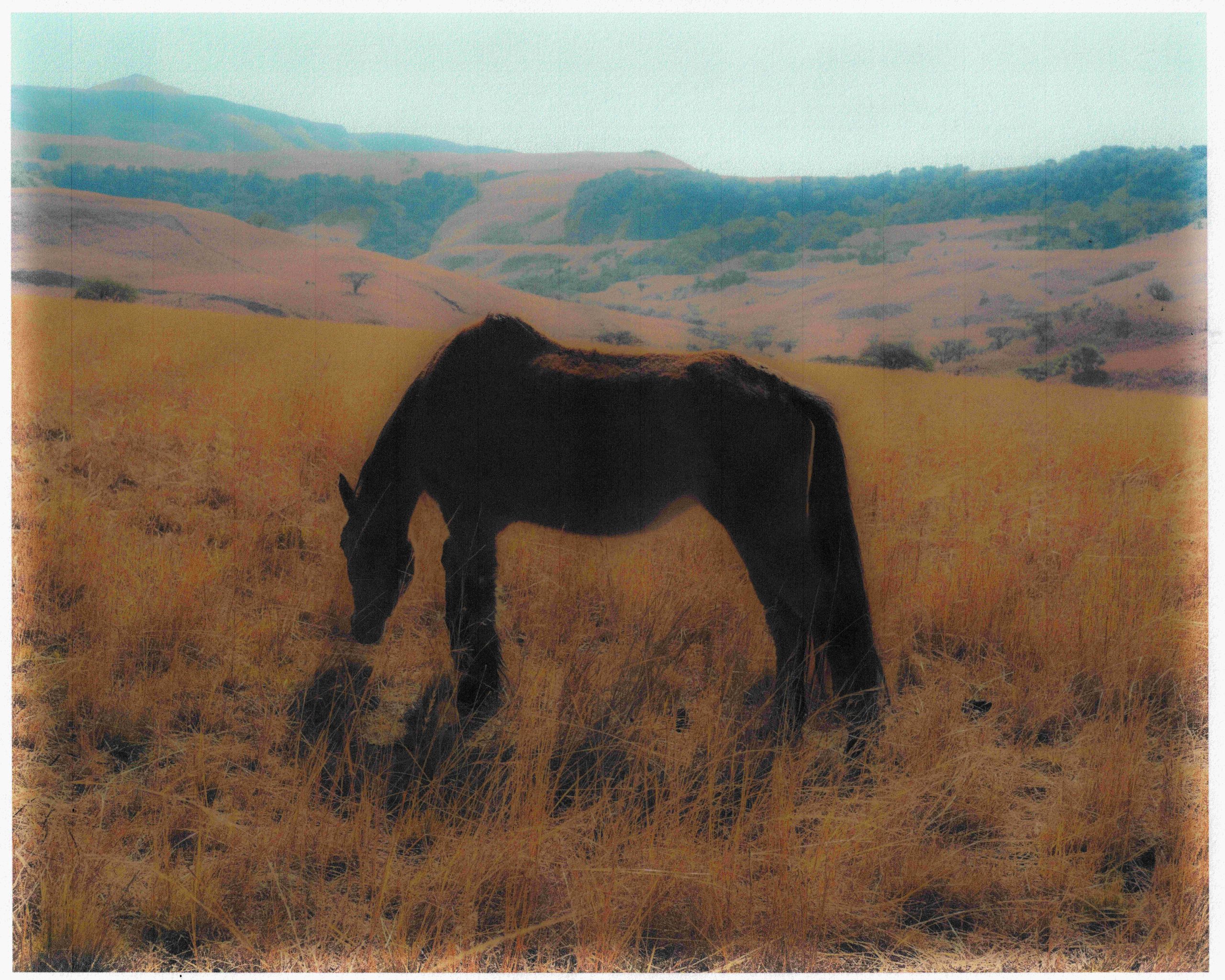

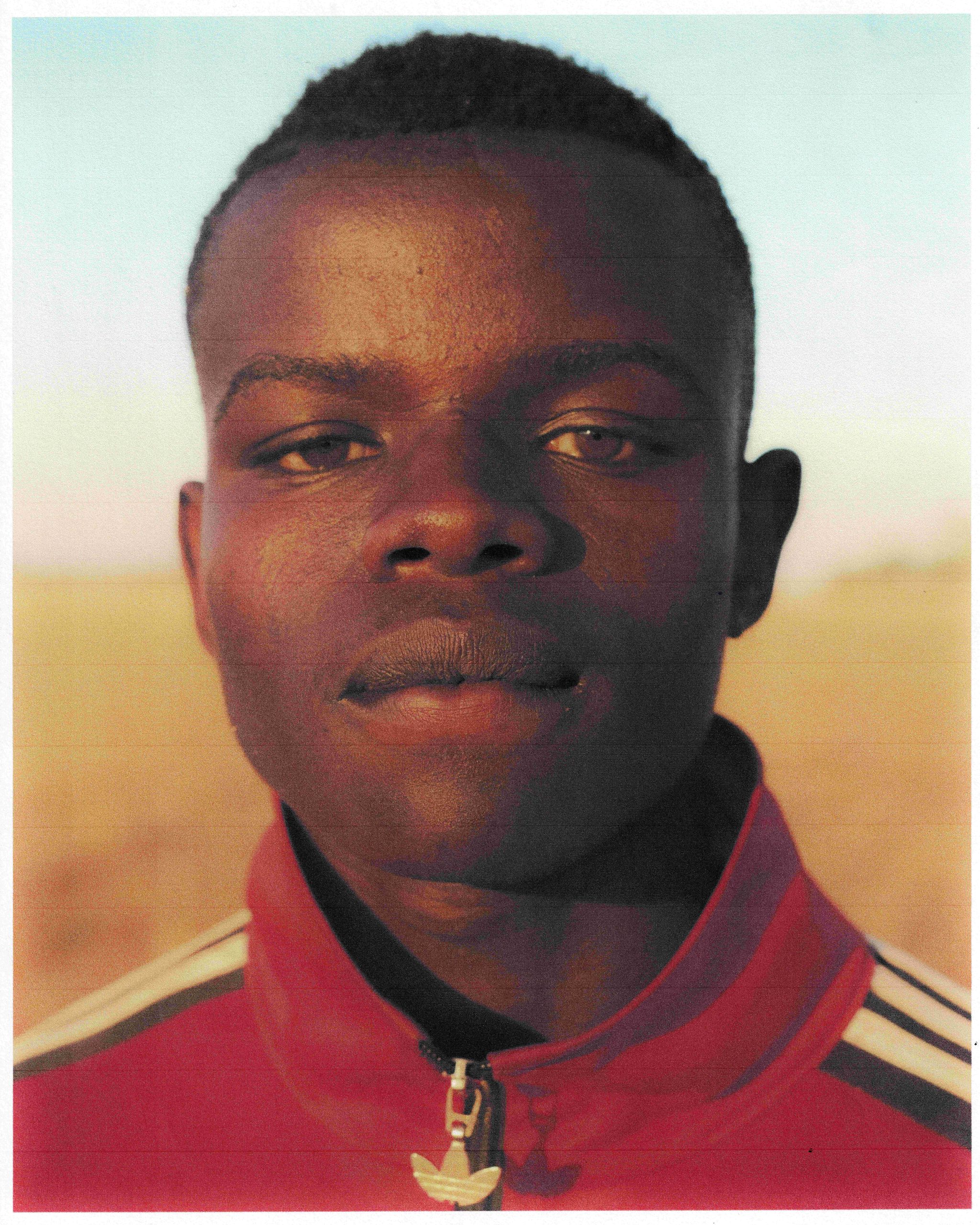

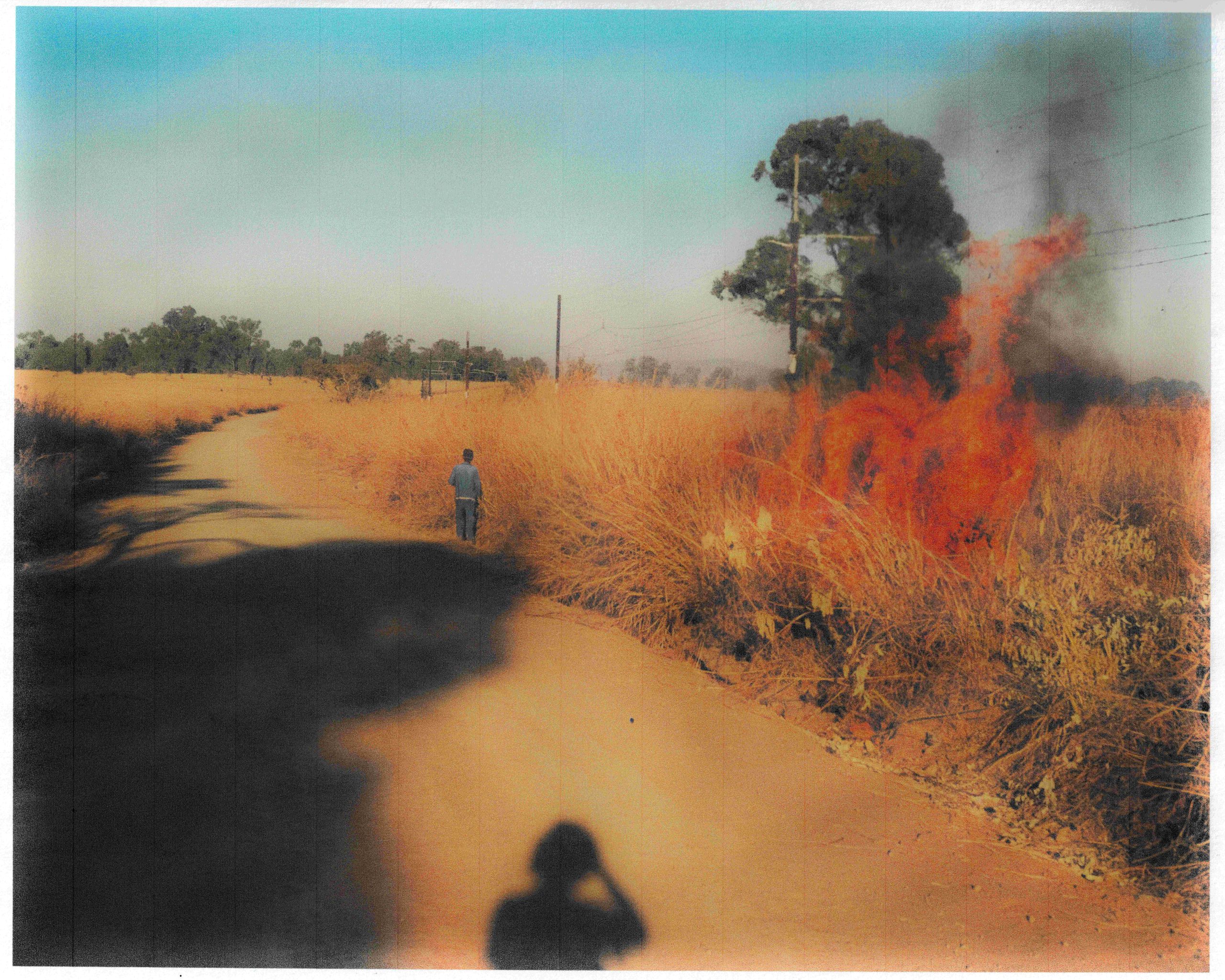

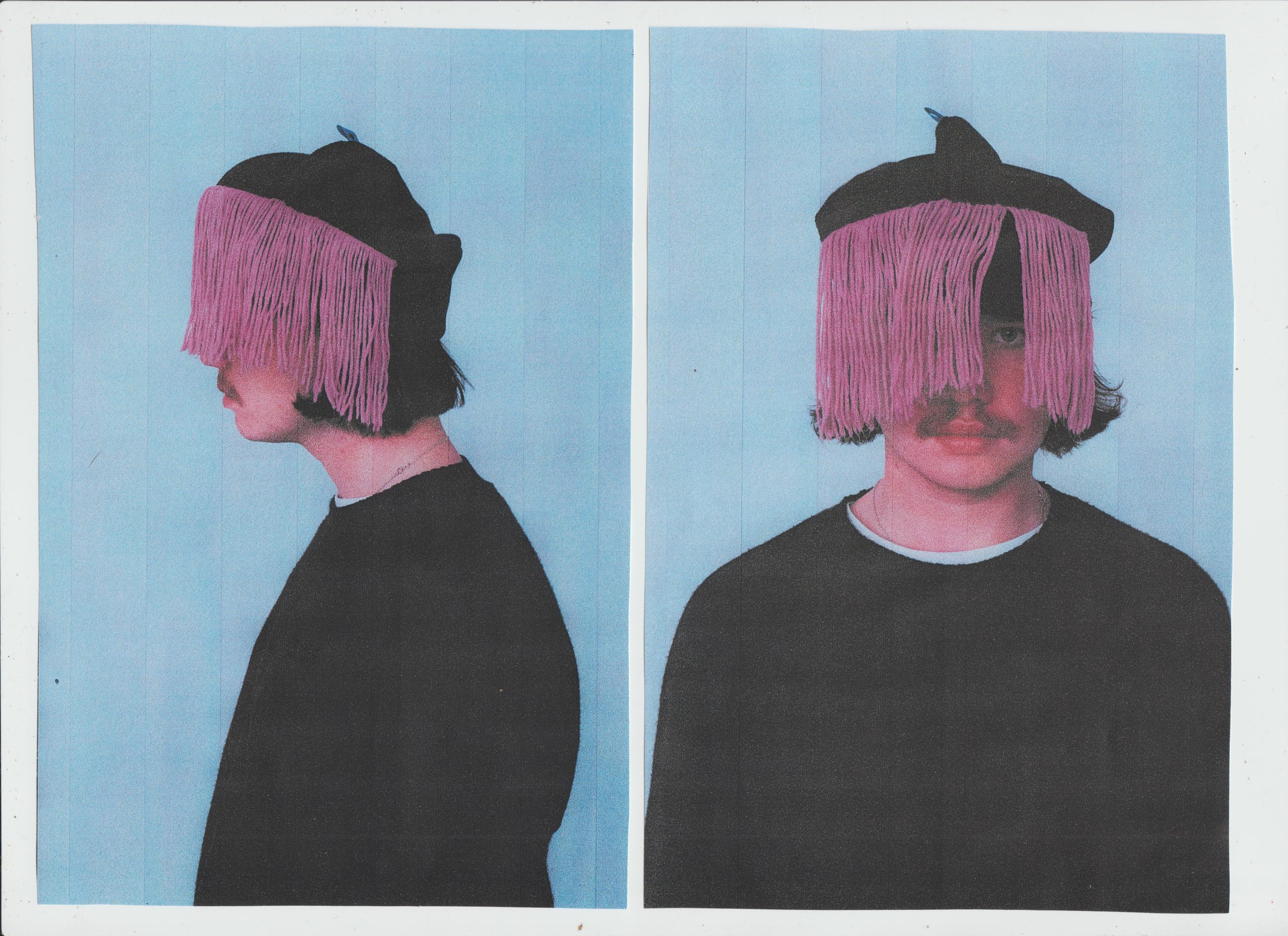

Fynn’s work can’t necessarily be summarised by the subject matter he turns his lens toward, as his work consists of landscapes, portraiture and more documentative work. However, there is a throughline in the visual language he chooses to express and present his work. A tantalising desaturated tonal paradise, as if the images had been washed and left out to dry in the baking South African sun, which he achieves by making prints of analogue and digital work he produces and then re-digitising these prints by scanning them.

However crude the method may seem to you, it’s undeniable that they result in a wonderfully textured, grainy, almost nostalgic visual language, as if the paper itself has clung to every single piece of ink it has been seeped in. Visually it’s reminiscent of how newspaper images seem to bleed as if they are trying desperately to hold onto the ink printed on them. For Fynn, however, the process and visual language he adopts have a far more significant meaning than simply chasing some visual aesthetic.

I first encountered this style you’re referring to in experiments with other forms of artistic media, funnily enough. At the beginning of this year, I found myself drifting away from photography and into film and stop motion animation, and it’s there I guess this style developed. Initially, I just wanted to find a way to digitise my drawings, so I could lay them in a timeline in Resolve and create the illusion of motion. After a while, however, I fell in love with the strange grain and almost dissociated look that came with the process of printing and scanning paper, and I think I’ve never looked back since.

I like the way the aesthetic creates a distinction between reality and a somewhat fabricated world; a world I’ve created, which for me, speaks more to my internal reality than anything else. I have been trying to find ways to portray my subjects in unfamiliar manners for a couple of years, and currently, it feels like this printed and scanned aesthetic speaks to where I’m at, and that’s all that really matters to me when deciding on the construction of a visual language.

I’ve often talked about the charm surrounding the tactility of analogue photography, even if it’s simply receiving your negatives back. In an ever-digitising world where less and less of the things we see and feel seem rooted in a semblance of reality, there’s an underappreciation of how present and rooted tactile elements can make us feel. There’s a sense of reality or at least created reality that, in my opinion, can be invaluable. Fynn’s process takes this tactility to a whole different level, engaging with his work in a conscious and tactile manner that in turn serves as his own unique way of feeling connected to the world.

When I first encountered this aesthetic, we’re speaking about while printing, I remember being overcome with feelings. It was like I had invented a way of being able to physically depict how I felt, which I’d never been able to do before. Immediately I became obsessed. I wish you could have seen my room at stages of this year. It had prints and drawings everywhere, which I’d made to make myself feel connected to the world again. I take this style with me almost everywhere as my own personal means of connecting to people and my surroundings.

Those who have DPD will know what I’m talking about; everything feels weird and unfamiliar, and it’s like, even after nearly 23 years of living, you must find ways to piece yourself together again. This is exactly what my camera does, and it’s why I’ve had it in my hands so much recently. This year has been really tough, and I’ve been using my cameras and this style as a way of coming to understand it all. The grainy, washed-out look and under-saturated colour implicated in the technique is what speaks the most to me.

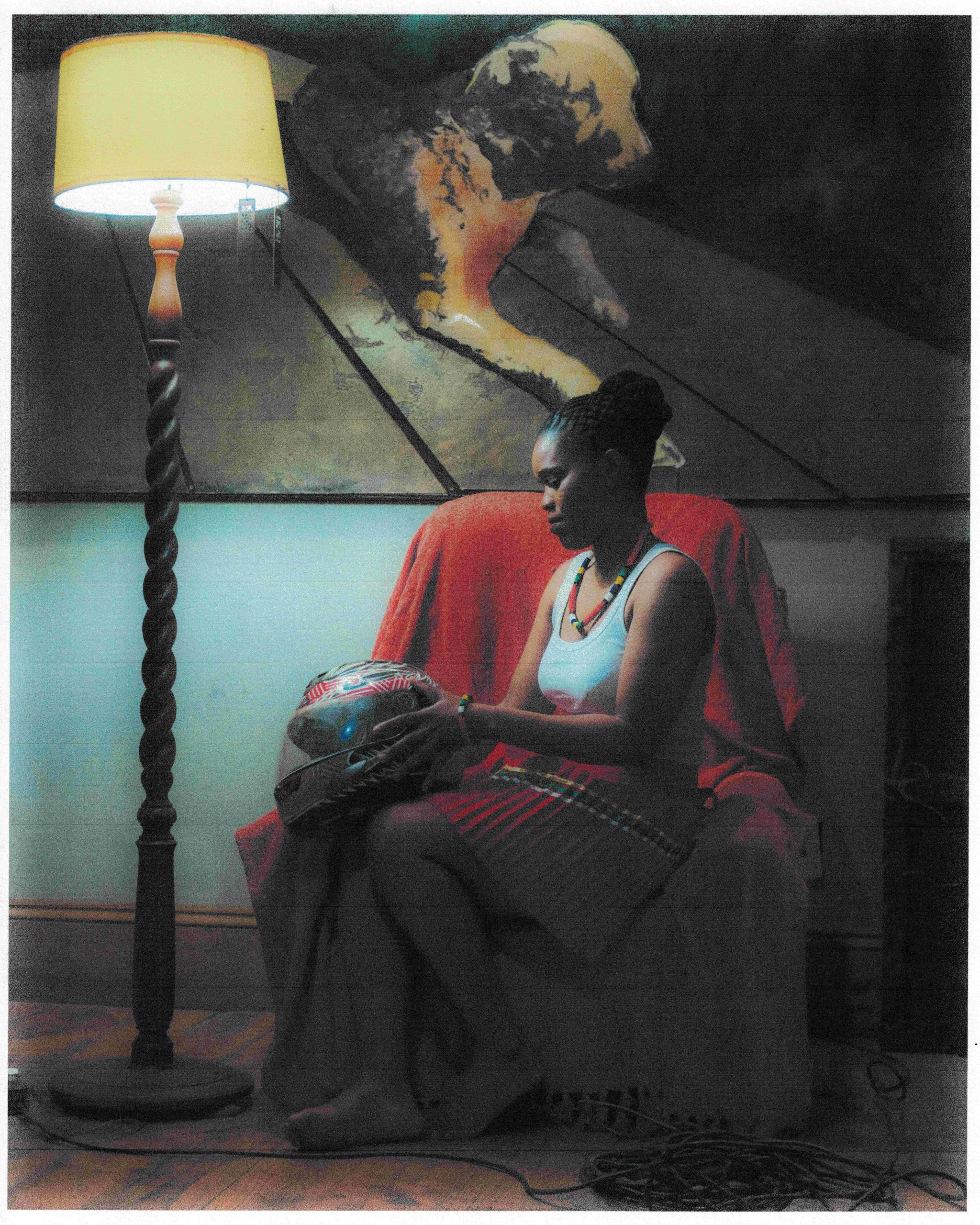

My favourite image from ‘Whispers and Counting’ is titled ‘Nana, Jaap’s Caretaker’, and it involves manipulation of these three elements. It depicts Nana holding Jaap’s motorcycle helmet facing the West in front of Jaap’s painting in his old bedroom. Nana looked after my uncle in the months before he succumbed to a brain tumour earlier this year. I think I made this photograph to come to understand his passing and what it meant for me.

Composition is also a key facet of this style we’re talking about. Although it’s mostly visual, I composed this photo in a way that I hoped the style would accentuate. The image has a lot of negative space connoting absence and Nana’s pose is quite gentle and melancholic. Printing the image gives that negative space texture and provides insight into her pose, and I like that. When I printed and edited the photograph, I did it in a way that spoke to the confusing feelings I was forcing myself to come to know better. The gentle, dissociated look of the image speaks to my general feelings involved in depersonalisation. I didn’t feel very present while taking the image, and I wanted to depict it in a dream-like manner that the style allows for…I also enjoy how the style creates a feeling of a “different world”.

I alluded to this earlier but living with DPD is like living in a dream. The qualities of the image really make me feel seen and understood, and I hope they do the same for others living with DPD too, or for anyone who feels like their world is confusing and dream-like, really. Ultimately my images are made for me and my own self-understanding, which I guess is beneficial to society at large, although it makes me really happy to know that others resonate with them too. I hope they make you feel seen and understood in a small way.

I’ve always appreciated artists that move against conventions. Yes, his process means that the images aren’t ultra sharp and that the manner in which colours are presented may seem unfamiliar, but at their core, they do what great images do. They make you feel and think. They are more than an attempt to simply document a moment but rather an emotionally informed snapshot, capturing the beauty of imperfection.