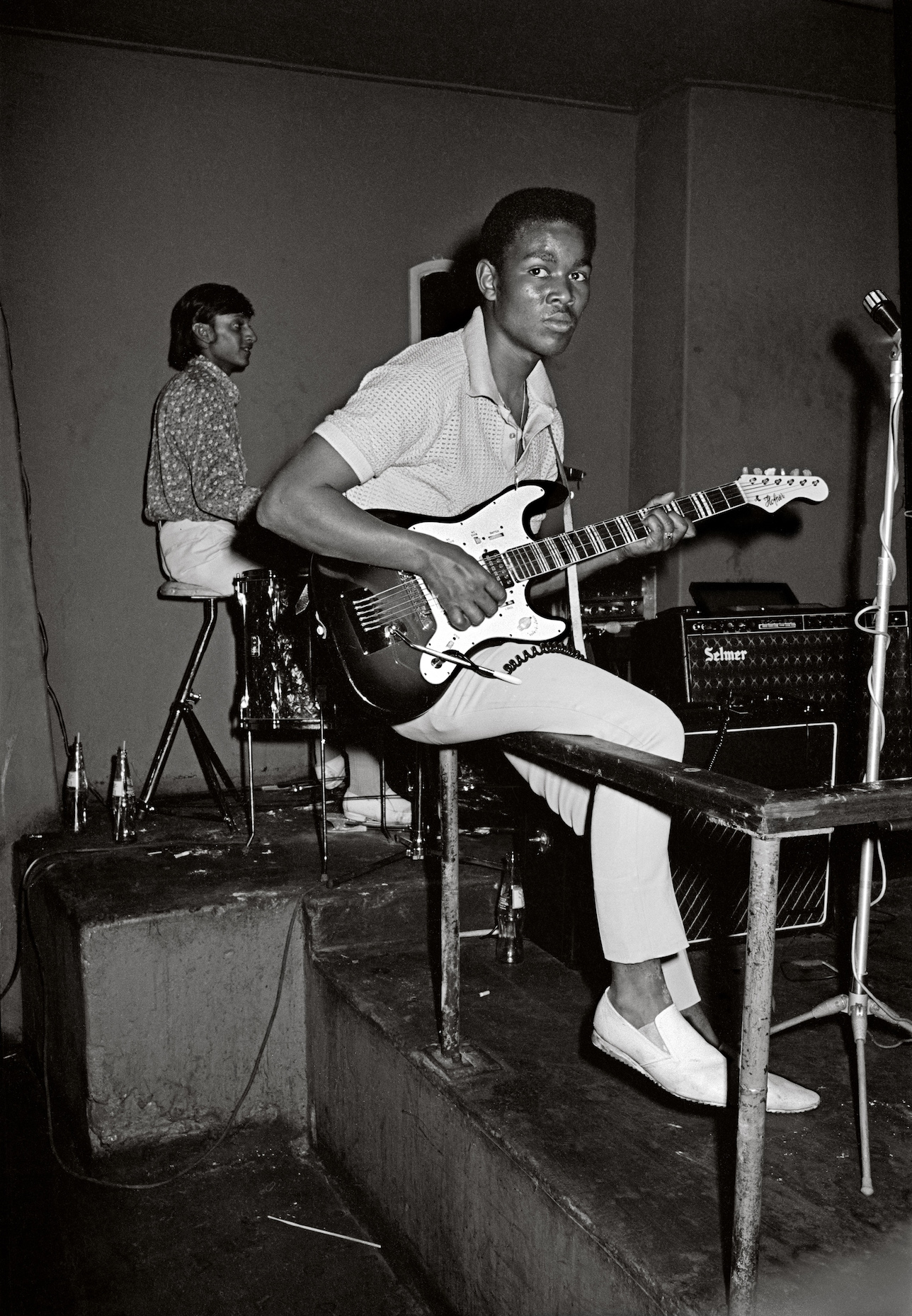

As your body descends into the underground the darkness slowly caresses your cheek. You are met by a crude yet unflinching interior as you try and find a seat to call yours for the night. A safe space, a ‘third space’, this is Cape Town underground. Loud, dark, dingy. A live jazz band competes with the sound of laughter and cheering in several languages. The walls are fifthly and the floors reek of brandy, sticking to your feet. This is a description of what it must have been like to party at the infamous dockside nightclub the Catacombs in the 1960s that is best remembered through the photographs of Billy Monk.

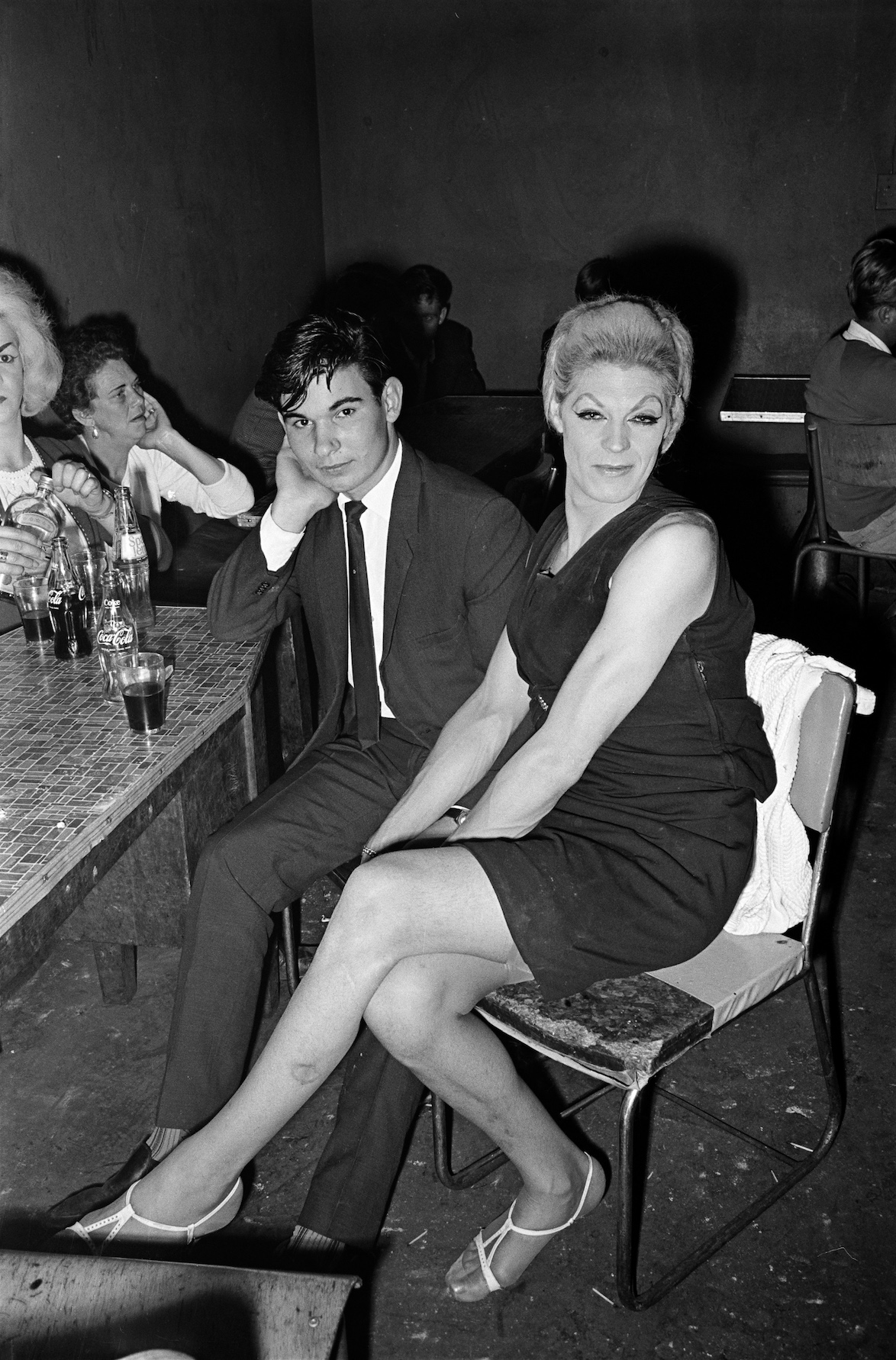

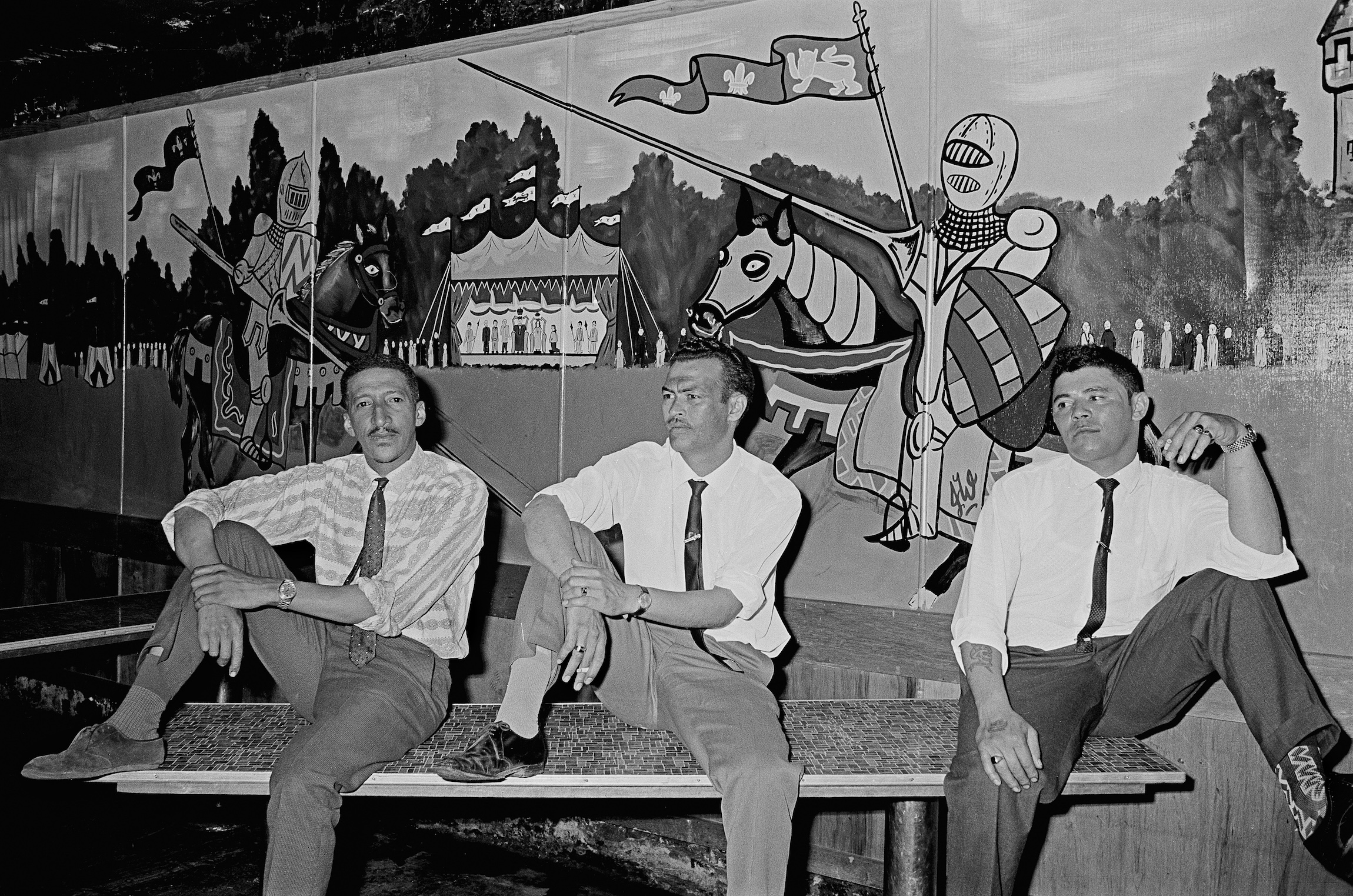

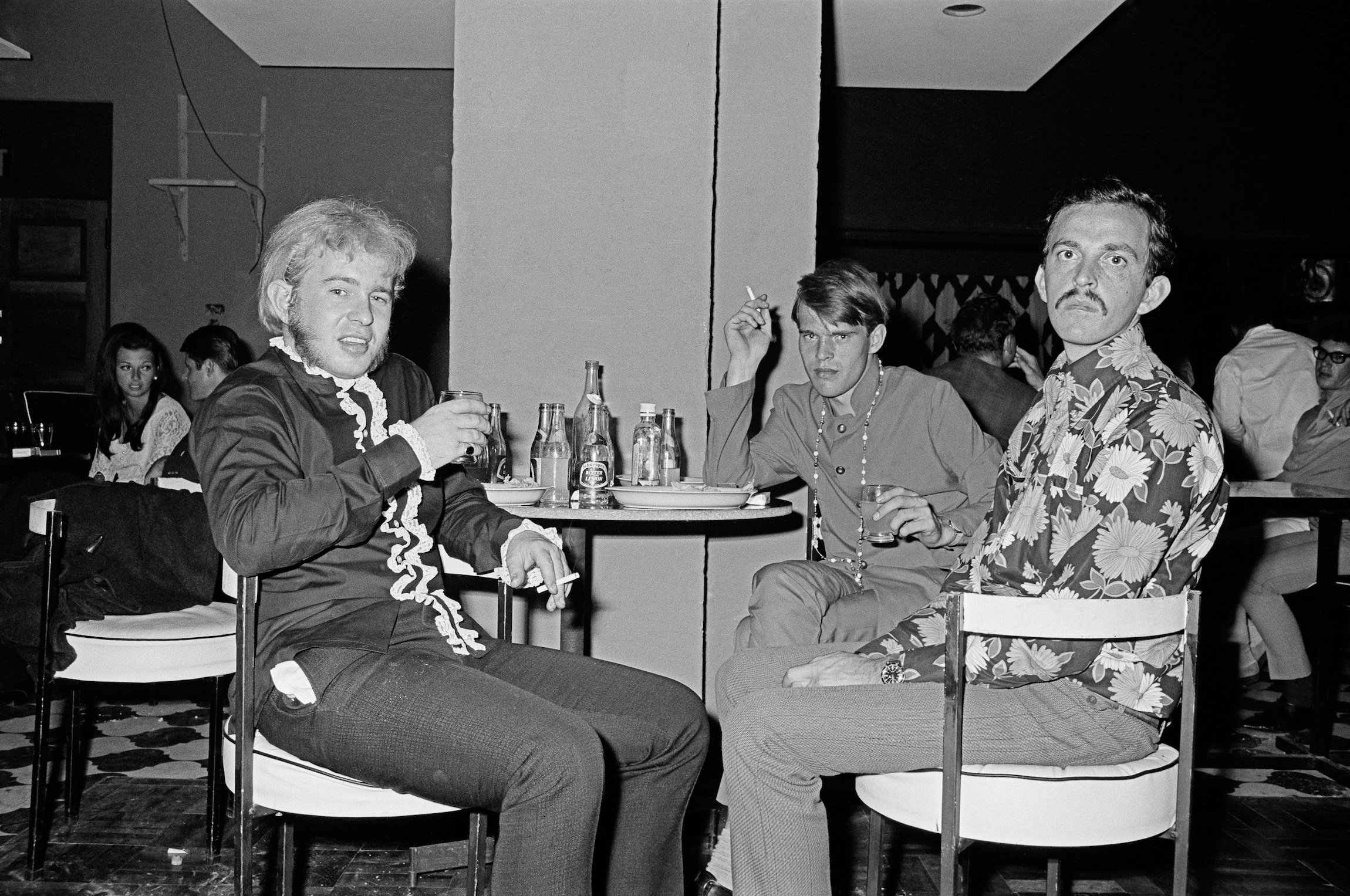

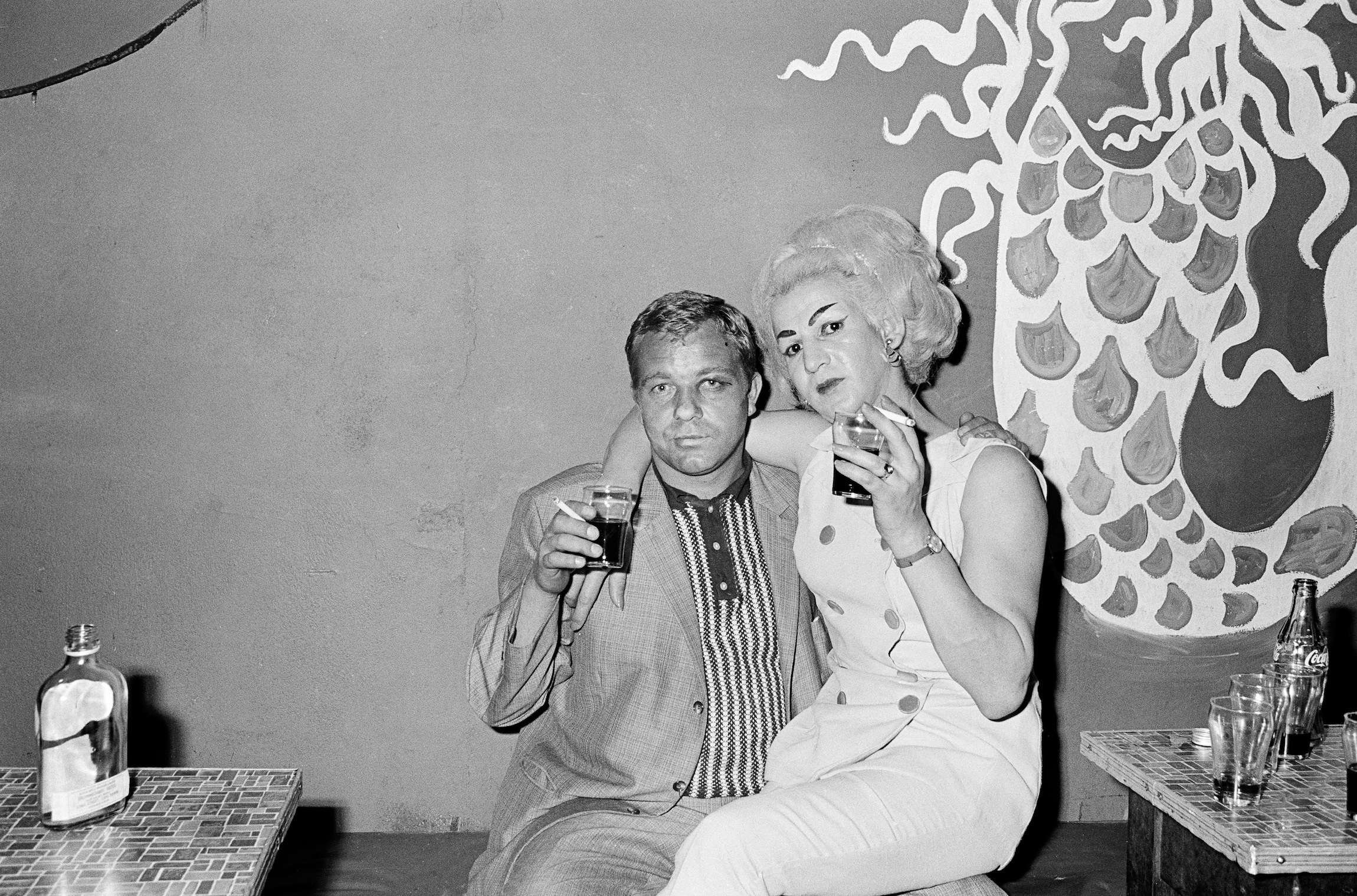

What can be described as a liminal space was formally situated within a ‘white’ area of Cape Town however the people that partied there did not heed to the laws enforced by the apartheid government and welcomed the diversity present on the dancefloor. All were accepted at the Catacombs it was a space for outsiders by outsiders with a devil may care attitude and a taste for indulgence. An inclusive space in the midst of apartheid Monk’s images immortalize this history with snapshots depicting members of the LGBTQI+ community, sex workers and sailors to name a few.

Billy Monk is in many ways an anomaly with a tragic life story. A drifter through life he had a few shifting jobs: a leather sandal maker, a crayfish poacher, a vegetarian food vendor, a nightclub bouncer and a photographer. Known for his short temper, the bisexual photographer was always looking for new ways to make money and was thought of, by some, as a small-time crook. “He lived and breathed this underground world, documenting the people he knew so well, while also enjoying the seedier aspects of the job. He was known around town as a womaniser (although was open to affairs with men too) and although also described as a true gentleman, wasn’t afraid of a fistfight,” states Craig Cameron-Mackintosh the archivist and manager of Monk’s estate.

In a society – South-Africa under apartheid – that sought to objectify the world, to reduce its people to objects, and to amplify the technical means to do so, Monk’s resistance is as ethical as it is existential, as metaphysical as it is mysterious.

– Ashraf Jamal

Close in proximity to District 6 the frequenters of the Catacombs placed emphasis on interdependence and acceptance. This space became a territory for a transnational milieu. The dockside was a global cultural intersection due to sailors from all over frequenting this space. Trotter, as sited by Jamal, concludes that the Catacombs’ frequent inhabitants’ cosmopolitanism was an accident of their environment.

The plunder of District 6 meant the annihilation of a key socio-economic and cultural point of contact. The impact of this should not be disesteemed. Monk’s work becomes a physical record, evidence of this transnational and –cultural moment before its erasure. His remarkable body of work ascribes its own value. Stripped, these images speak of the humanity of the moment in question.

The lack of significance placed on his work after the toppling of apartheid is explained by Jamal as a matter of the subject matter of his depictions not corresponding with the objective of orthodox resistance culture. His work was not deemed fit for canonization as can be seen through the show ‘From the Bridge to the Catacombs club’ at the South African National Gallery in 1993. His work was instead left to slip through the cracks of history; Jamal speaks here of an absent-presence in the South African cultural imaginary.

His work is “by an insider of insiders for insiders”, the irony lay in the fact that they were only insiders among themselves and in the grander scheme of things, in the light of the oppressive apartheid system and regulations they were subjected to, they were outsiders.

As the apartheid government came up with new regulations to police bodies with and enforce segregation even more steadily, in 1966 relationships between different ethnic groups were curbed by the Immorality act. And here is a point of immense power that Monk’s work holds. As it is a document of openness, acceptance and love in a time where it was literally illegal to share intimacy with a person from a different race than yourself.

As these images were made by him for the people he photographed (like event photography) these images could possibly have lived in the shirts of sailors or the jewellery boxes of sex workers, acting as covert trophies of private resistance. As Cameron-Mackintosh explains “Through research, interviews and reading old letters written by Monk, it’s evident that he had no intention of making any social statements with his work, but he did have visions of becoming a well-known photographer. He was simply documenting an exciting world that he was a part of and had nightly access to. Most of the images in his archive are posed happy snaps, destined to be printed as postcards with ‘Photo 67’ stamped on the back (1967 was the year he opened his studio at 42 Kloof Street) and sold back to the subjects as souvenirs.”

It would be years before his work was discovered in his old studio and reprinted by Jac de Villiers and Andrew Meintjies. In 1982 his work was exhibited at Johannesburg’s Market Gallery by De Villiers with the blessing of David Goldblatt for the first time. It is on his way to this exhibition that Monk was shot dead. In 1993 the National Gallery showcased his work in ‘From the Bridge to the Catacombs Club’. His work is then ‘missing’ for nearly two decades before it appears in the exhibition ‘Jol’ by SANG curator Pam Warne. This marks a turning point as in 2010 it is showcased at the Brighton Biennale and the consecutive year is followed up with a retrospective at Stevenson Gallery. His images exist under erasure, excluded by the dominant narratives of oppression and resistance.

Of course, the question comes forward as to why these depictions of such a singular history become forgotten especially soon after their professional recovery by De Villiers. One explanation could be that in the 1980s (the Immorality act still in ‘place’) it was seen as too risqué to release Monk’s body of work. His repertoire, it is important to note, is neither resistance art nor does it depict a moment of post-resistance during a psychic oppression. The photographic occupation in this country as argued by Jamal is that of documenting lovelessness (violence). He continues this thought by stating that it has “…. informed, arranged, and sold South Africa as a pathology.” In the same sense Monk is not a Roger Ballen or a Diane Arbus who purposefully seeks out the ‘spectacular’ within humanity to create from. Monk does not ‘take’ with his lens, his photography is an expression of love.

Despite the use of a stark flash, his sitters emit an immense presence in every frame. Acting as defiance of the accepted rules of perception/perspective, in other words, his work defies how his sitters should look or should be framed. The excessive meets the banal giving his depictions agency as they are a manifestation of convention. The commonplace framed ethically. His work lay in an instance that is neither grand nor dreadful. He is then just a photographer of life. In terms of its emotion, Monk expresses tenderness in his reflections. He does not objectify his sitters, he does not make them out to be anything more or less than what they are, he does not seek for them to represent some higher meaning. He does not dissect his sitter he merely takes a look. Honest, radical.

“Billy Monk artfully documented the people he knew inside the places he inhabited. Many of them were outsiders, whether due to race, sexual orientation or class. The freedom of the Catacombs is illustrated in stunning images of gay and mixed-race couples and the group of transgender women who dressed to the nines each weekend. These aren’t the sort of photographs you would associate with 1960s South Africa. And rather than shy away from the scrutiny of Billy Monk’s camera flash, they all open up to the camera with a playful sense of ease,” expresses Cameron-Mackintosh.

What is interesting about the work that he created during his time spent in the vicinity of the Catacombs, is that despite them being subject to the time they were captured in they are wildly out of their time, again this could be as a result of his work having been sporadically forgotten. These images were anomalies when they were created as they are now.

Neither objective nor nostalgic, neither reflexive nor coolly matte, Monk’s photographs challenge not only the limits of the technology which produced them but the codes to which criticality might reduce them scandalous subversion of the oppressiveness of South Africa’s policed culture at the time.

– Ashraf Jamal

It has been half a century since Monk took his last snap in the Catacombs and since this time less than fifty of his images from the archive have been published. 2019 will witness never before seen work by the photographer at the Investec Cape Town Art Fair from the 15 – 17 February.

Reference:

[1] Ashraf Jamal, Billy Monk: Love in a loveless time, Image & Text, Jan 2013