Having found our way out of the peak of tabloid-gossip culture, much amends is still to be made to ensure the institution of the media never treats people the way Britney Spears and Lindsay Lohan were treated ever again. Since then, a glacial shift with increasing momentum has been taking place. It started by a removal of the rose-coloured glasses that desensitised us to the flashing lights of the paparazzi and asking: what even is a celebrity?

The Old French root word celebrité translating to “celebration” reveals a lot about what role celebrities have traditionally been assigned. These are members of society who we’ve celebrated, honoured and uplifted. The hysteria associated with celebrities made it an expected thing that fans would scream their way to unconsciousness at Michael Jackson concerts they expected to see him at. In many instances, the celebration (read: hype) comes before the very thing being celebrated. It is largely accepted and understood that bona fide icon Paris Hilton is “famous for being famous”. Somewhere between low-rise Juicy couture bedazzled tracksuits and the pandemic: something changed. Ushering in the era of discourse captions. The critique of femme entertainers moved away from misogynistic-career damning-nip slip-slut shaming to a more rounded engagement that also calls into question the celebrity industry they inhabit. While there are still corners of the internet where the central rhetoric flows from patriarchal ideologies, prevailing popular culture is focused more on holding celebrities accountable in a way that also brings questions of social/racial justice into the fold. Leading to what some have called a perpetuation of “cancel culture”. It seems to me that “the celebrity” now exists less as a celebrated person in society and more as an ambitious job title. A job — like any other — where the person appointed can be subject to reprimand and demotion. The celebrity is uplifted to a place of hyper visibility, however, not to a state of absolution.

Paris Hilton, (sourced from internet archive)

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, (sourced from internet archive)

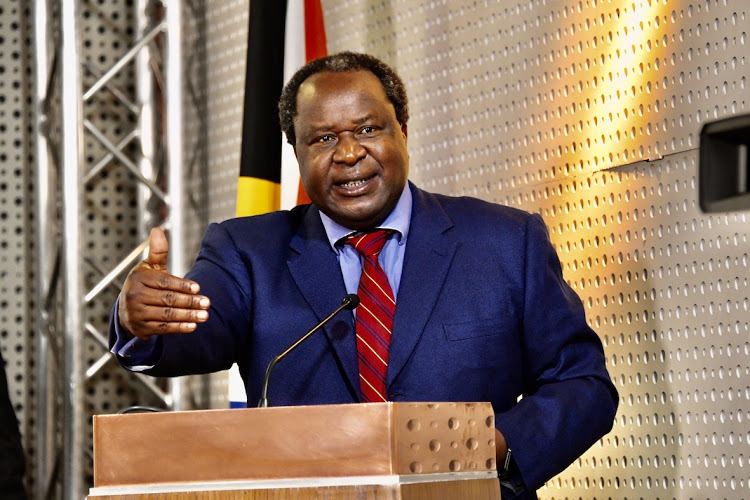

The last year has seen a lot of frustration, and with it, the invoking of more class consciousness. While we’re a long way from reciting the Communist Manifesto from memory, social media users have raised their eyebrows up at the unceasing flood of holiday pics from the likes of Dua Lipa on Instagram. Fans (likely from the confines of their room) justly asked the popstar to “read the room”. When 15 years ago it was to be expected and even celebrated that conventionally attractive celebrities would jet sail the world with bikini in hand, fans now plead with their faves to not be embarrassing. At the forefront of the anti-celebrity era is a call for politicians to stop being praised for doing their job. While a voice like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’ (AOC) has come to be a long sought after representative voice of some leftist views, many have taken opposition to the fact that she has been lifted to almost celebrity status (with fancams and all). While both politicians and stars were lifted to position of prominence by people in society, the very defined line in the sand is the purpose. On one side, we might have entertainers, practitioners or artists. On the other, we have public servants. No one understands the argument better than South Africans who have taken an issue with a kind of celebrity persona local politicians have adopted. Current Finance Minister Tito Mboweni has received his share of backlash for assuming the role of social media personality. Amidst an economic crisis, the Finance Minister’s tweets show someone quipping jokes about his own cooking, publishing covers of Irish songs, partaking in viral dance challenges and making tone deaf jokes about people asking the government for food instead of growing their own. The problem is of course greater than one minister’s tweets, but rather, is in where priorities lie.

Dua Lipa, (sourced from internet archive)

Tito Mboweni, (sourced from internet archive)

Two truths exist simultaneously: we can’t afford to take the politics out of pop culture contributors’ actions; and politicians — who ought to be preoccupied with politics — can’t afford to be those pop culture contributors. It almost seems paradoxical, but the rules of the game change with the times. If Pop Art taught us anything, pop culture should be fun. Ultimately, celebrities and high-ranking politicians still enjoy access to things ordinary citizens would never enjoy. The lines in the sand just help avoid making reality TV stars presidents for 4 years. The hope is that Icarus might be able to see the lines in the sand from all the way up there and know not to fly too close to the sun.