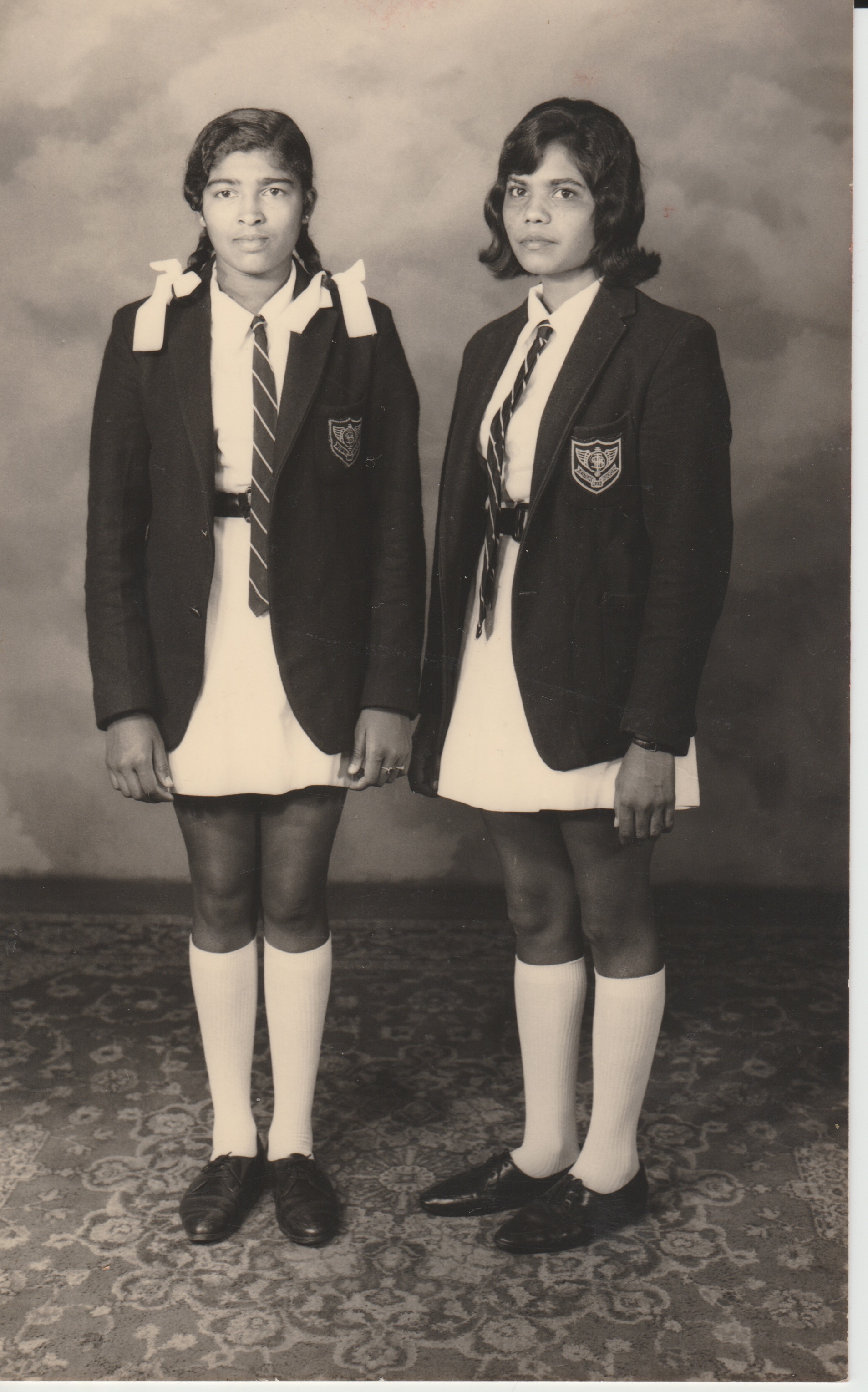

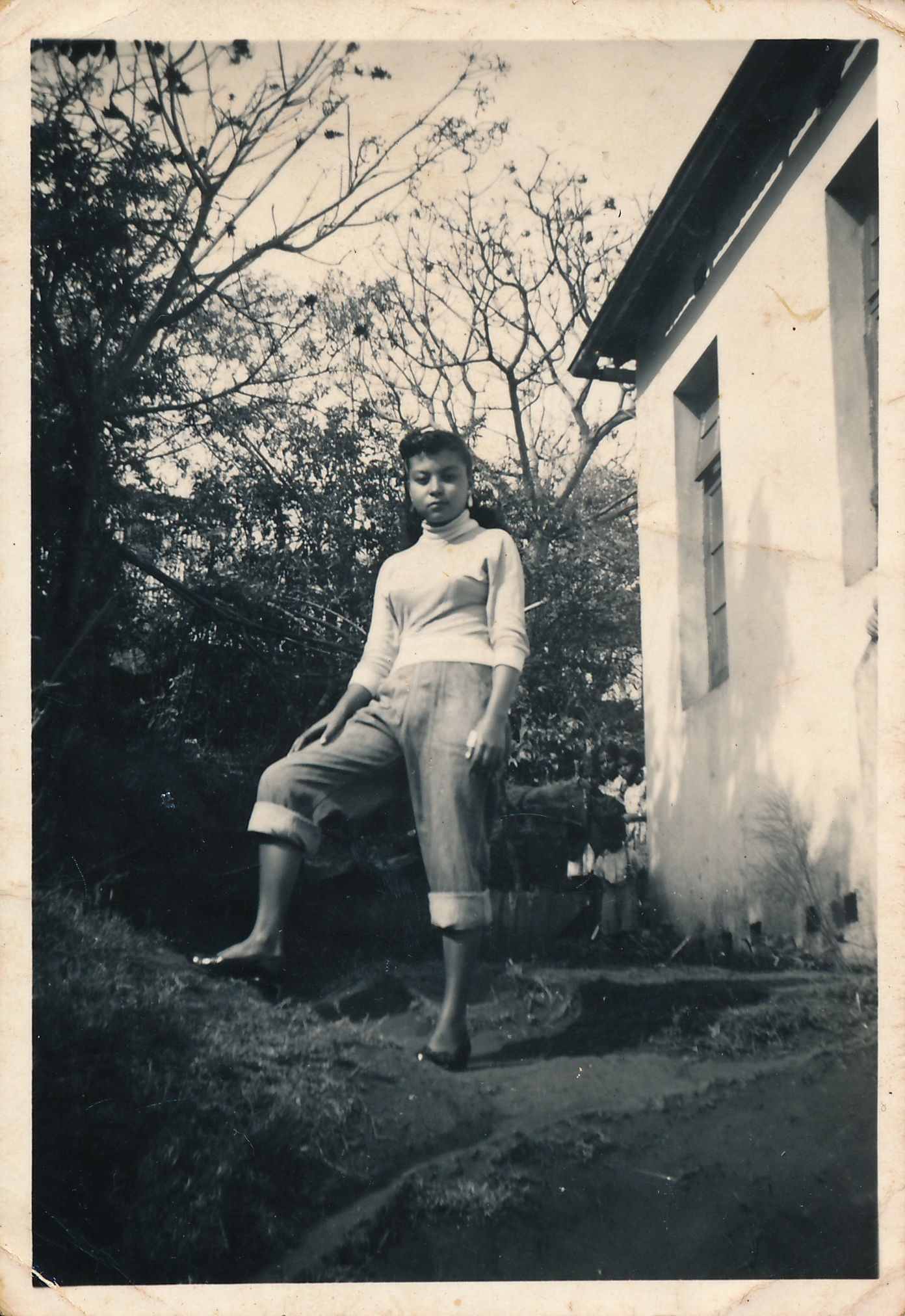

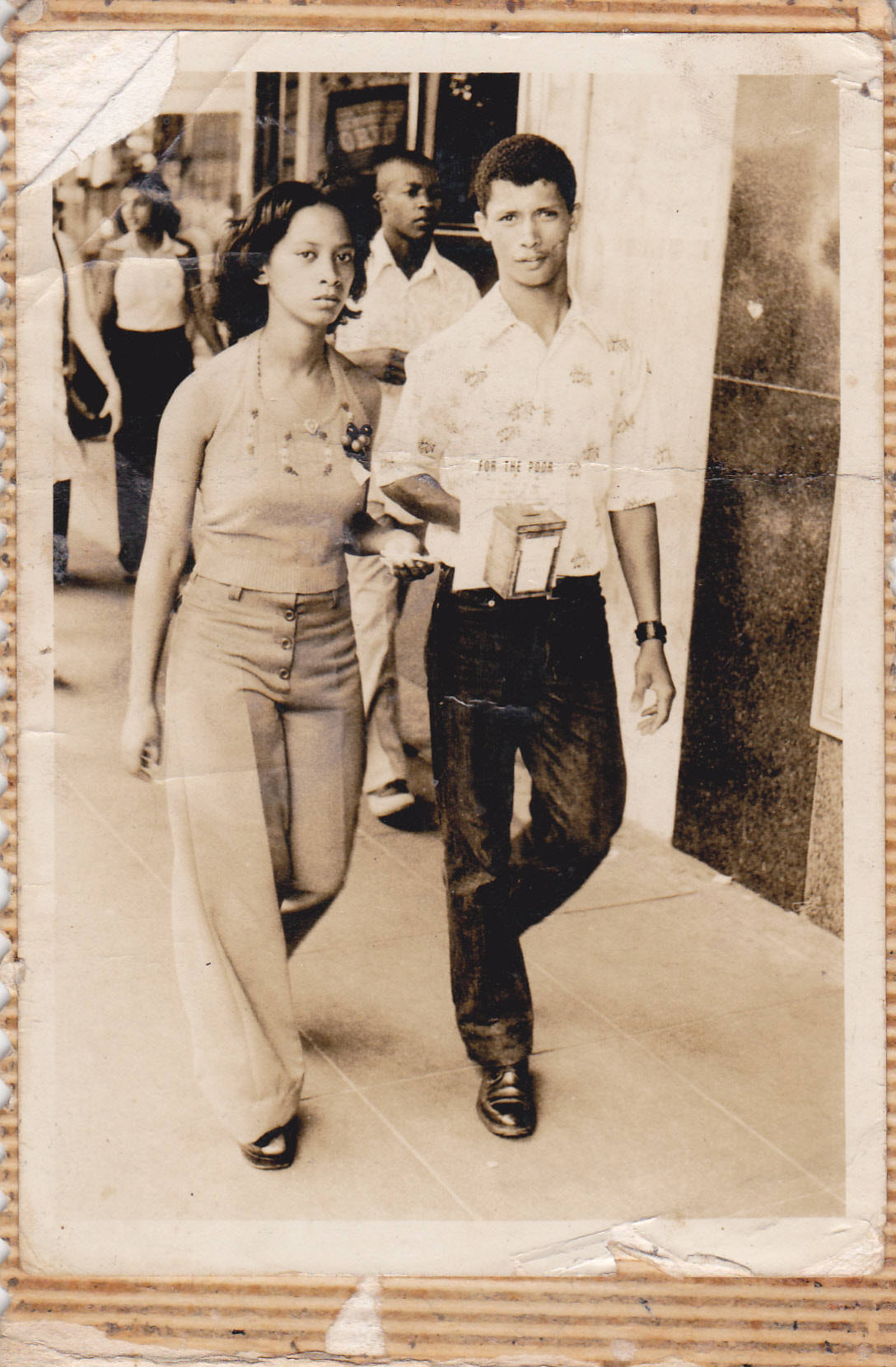

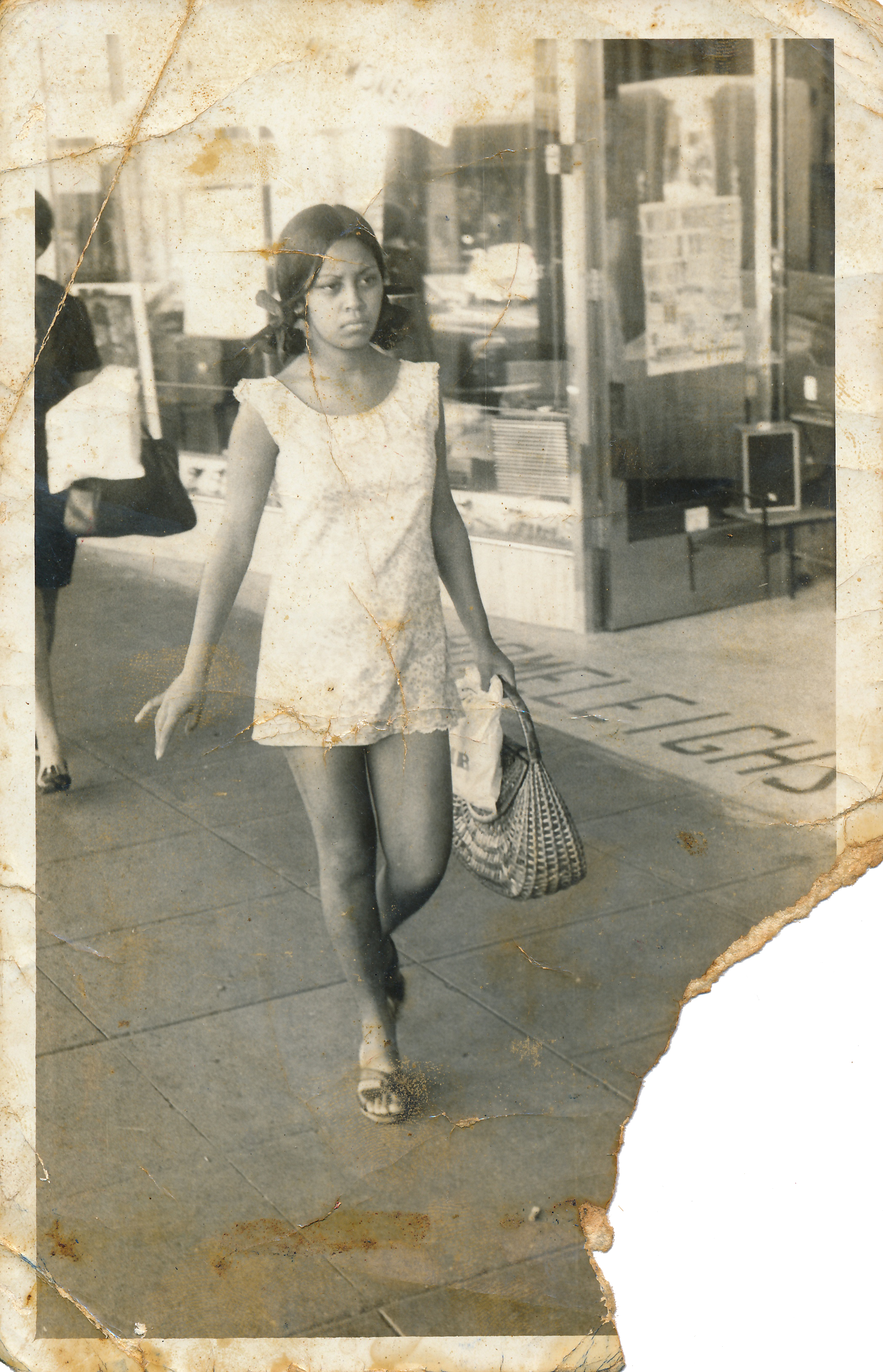

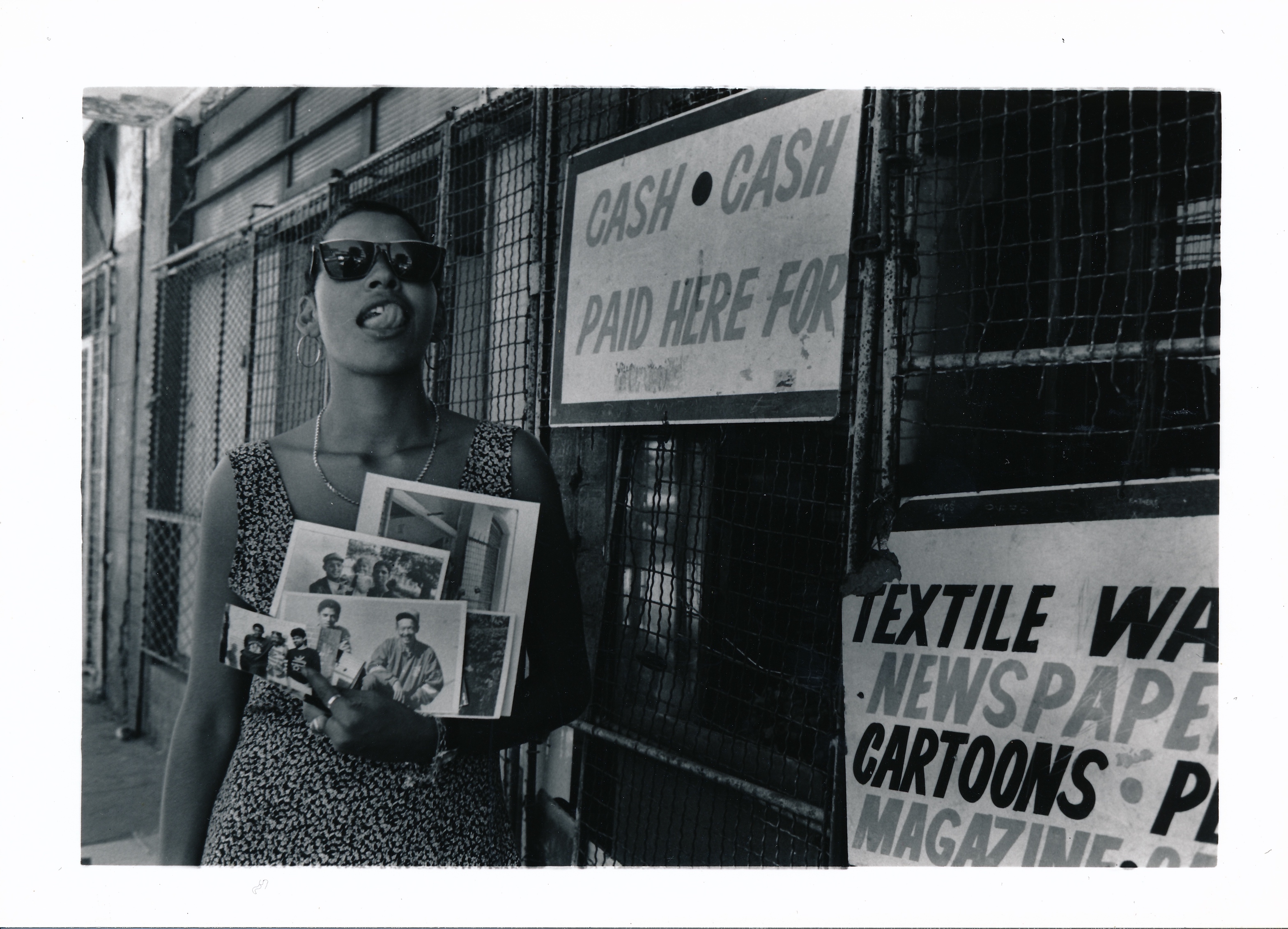

‘Proclamation 73’ set in motion by Zara Julius and Chandra Frank looks at the curated history of the family albums of people racialized as ‘coloured’ and ‘indian’ under the Group Areas act of 1950 in Durban. The exhibition is focused on capturing everyday lived experience, inspired by the family histories of the project leads. Loss, home and kinship become an intimate conversation through family snapshots of ballroom dance contests, beach days, wedding pictures, candid moments and street portraits.

The exhibition acts as both a challenge and an investigation of how different racial histories and segregation prevails within Durban and its surrounds. Images of the everyday share a space with aftermath images of forced removals in the region, a strong visual anchor that brings viewers’ attention to Proclamation 73’s disruption of static racial categories taking into account how categories such as ‘indian’ and ‘coloured’ were used as mechanisms of anti-blackness.

Spanning over a large frame of time the exhibition becomes nuanced taking a non-linear approach to fractured narratives and histories and brings together archives that are seldom viewed together. Visitors are asked to think through questions of erasure, representation and intimacy done through the portrayal of a wide selection of images, works selected from the collection of Peter McKenzie and Rafs Mayet (documentary photographers for Afrapix) as well as other archival materials.

As there was no existing archive which addressed the questions Julius and Frank were dealing with, images were sourced via an open call method which led Julius to make house calls with a scanner in order to obtain images as getting people to send in pictures proved difficult. Speaking to the non-linear curatorial strategy of the show Julius expresses “As a result of sourcing in the excess of about 900 images, our archive is around 1000 images, there’s no way it’s going to be able to fit into a neat kind of narrative. I think it is actually important, in my opinion, that we present these narratives as necessarily messy. They’re nuanced, they’re messy, no one’s lived experience is like someone else’s and therefore there is no need to try and create a linear narrative because I think that boxes history and stories and lived experience in a way that’s not particularly productive.”

Images of the aftermath of the forced removals echo back to a focus on lived experience as Julius explains the project is interested in the mundane, not the hyper-visible but the hyper-political as she expresses that what is personal is political.

“You’ll be able to tell what’s happening politically, or you’ll be able to situate someone, or situate a photograph in a context even if the photograph is just of someone in the botanical gardens on their wedding day taking a family portrait. It speaks to a lot of things, it speaks to [for example] people’s income brackets. That they would go to the botanical gardens to take a photograph on their wedding day and we have a whole wall of these wedding photos taken in botanical gardens.” How does the micro-narrative address the macro-narrative? the exhibition asks.

A horizontal dynamic of research was created due to the persons donating to the archive having the ability to choose which images they wanted to provide access to and thereby the stories that they want to tell. In other words, the way they want to present themselves or their family. Through this organic method of working a self-narrated history is documented and made accessible reiterating the importance of lived experience and personal history especially that of under-represented persons and or persons who have been erased from history by apartheid. The relevance of this project strikes as it opens up a platform for underrepresented peoples racialized as ‘coloured’ or ‘indian’, who have not been given a voice and –who do not have up until this point–an archive that tells their stories specifically in Durban, to visually narrate their lived experience and create their own representation. This method of self-representation is powerful as it is real life constructed by real people. These narratives and histories are told by the generous donators of the project and are therefore not constructed on assumption.

As a photographer, my curiosity was peaked upon initial readings of the show curious as to the opinions the curators hold on the question of whether snapshots could truly provide insight into the lived experience of an individual. Julius shares that in her opinion, a snapshot has the ability to do so on surface level. She elaborates, “…what these images really tell [us] is the autonomy of people to choose how they are depicted because we also need to remember that the majority of the exhibition is sourced from people’s personal family albums and the process of putting together a family album is one that is heavily curated. People especially before democracy, before a time when cameras were financially viable, people who were not racialized as white made a big deal of having their photo taken. People would hire a photographer for a wedding or a christening or someone that had a camera to loan them or they’d go to a portrait studio. So, what I think these snapshots actually show is people’s perceptions of themselves and how they want to represent themselves especially in an age where representation is so important and quite a prominent conversation globally with regards to people who are racialized…

For example, in the Old Courthouse Museum there were only 4 photographs of people racialized as ‘coloured’ and the majority of those photographs were kids in orphanages so that becomes a narrative. So when you bring a personal narrative into that archival space it really disrupts the power relations of representation. It also helps to disrupt a lot of narratives that the state has built about ‘us’…

These snapshots give us an opportunity to complicate and self-determine more than us trying to fully understand someone’s context. I don’t think that’s ever really possible.”

‘Proclamation 73’ is taking place at the Durban art gallery till the 15 February 2019