In an episode of Art Angle, a podcast by Artnet News, art critic Ben Davis and Artnet’s European editor Kate Brown discussed the emerging trend of Hypersentimentalism. Based on Brown’s Artnet essay How a New Wave of ‘Hypersentimental’ Portraiture Is Serving Up Painting for the Age of Vibe Shifts and Nano-Influencers (Or: Why is everyone painting their cool friends all of a sudden?), the conversation explored a trend within figurative painting that celebrates micro-communities as both content and sensibility.

In her analysis of Hypersentimentalism’s emergence in New York’s art scene, Brown suggests that Hypersentimentalists are reshaping contemporary art and notes the transformation of Sentimental Art from being historically perceived as non-political and soft, to becoming a language for avant-garde artists. According to her, the notable rise in figurative painting from 2012 onward recentered human subjects in art, gaining traction by 2014, and signifying a shift from the then-waning trend of abstract art styles like Zombie Formalism.

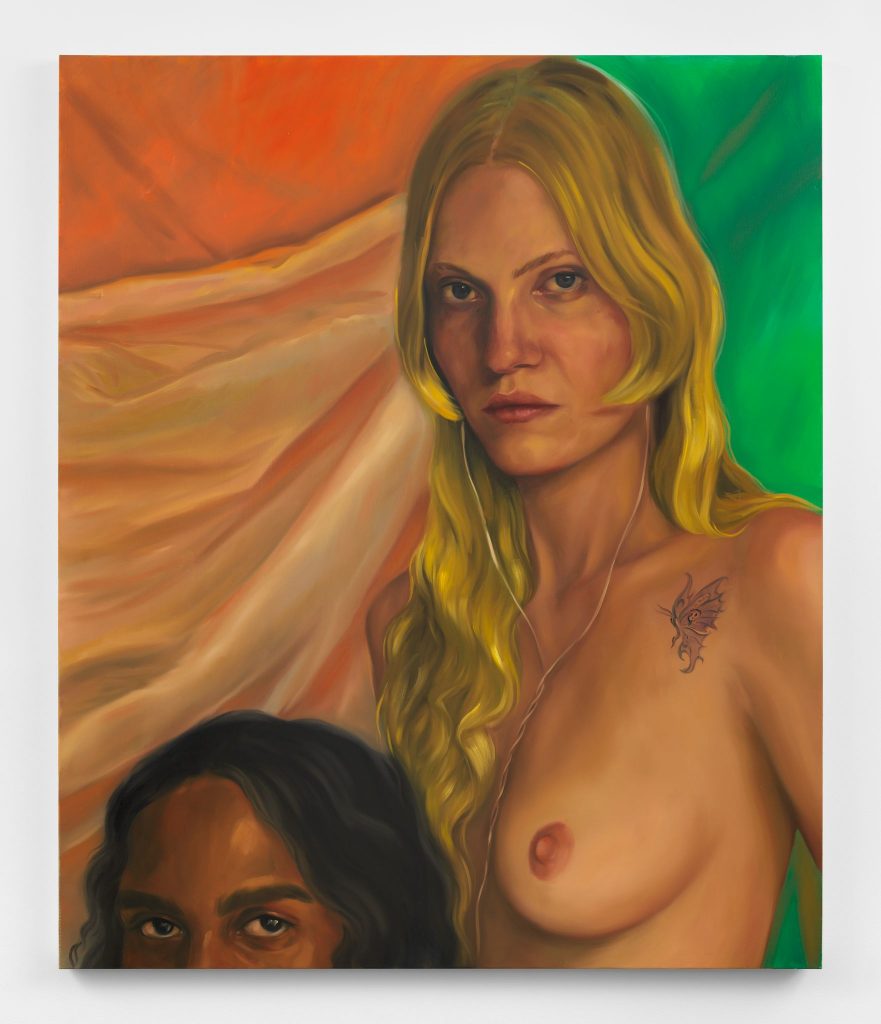

When asked about Hypersentimentalism’s distinguishing qualities, Brown underscored its portrayal of art community connections, offering it as a respite from hyper-political art and hyper-visible digital noise. “Identity-based figuration” within Hypersentimentalism, akin to selfies, merges expression with branding but adds an air of exclusivity, shifting from conventional portraits to viral-aware depictions of cool, famous friends. Such artworks flourish in online clusters and digital micro-communities by prioritising social status over artistic innovation. Brown wrote: “… the tittering online was not because the work was particularly stylish …”, speaking on Elizabeth Peyton’s Art Basel Hong Kong portrait of Lucas Zwirner.

The “hyper” in Hypersentimentalism intensifies this implication, like hyperlinks leading a viewer towards hidden information. According to Brown, encryption safeguards communities against co-optation, with hidden references fostering exclusivity while countering social media’s homogenisation and granting narrative agency. “… like a video-game Easter egg …”, such encryptions highlight personal relationships in a digitally connected yet emotionally distant world driven by algorithms.

Brown calls our attention to Tobias Spichtig, a Swiss painter residing in Berlin, whose exhibition Dear Friends (2023) seems to epitomise Hypersentimentalism with his portraits forming an interconnected row of emotional headshots that evoke a sense of connection within his hip artistic circle. Spichtig‘s modish painterly style portrays Berlin-based artists, collaborators and peers against black backgrounds, tapping into digital circulation and virality aesthetics.

Despite compelling instances, Hypersentimentalism lacks a singular qualification as a distinct artistic genre. Throughout history, artists have portrayed intimate relationships, inherently mirroring societal and technological advancement. From ancient rock murals to Renaissance maestros such as da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo, depicting companionship remains an age-old convention. Dutch Golden Age painters like Vermeer, van Eyck, Hals, and subsequent Impressionists like Monet, Degas, and Renoir consistently captured camaraderie. The advent of photography further paved the way for innovative movements like Post-Impressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism, each carrying forward this tradition.

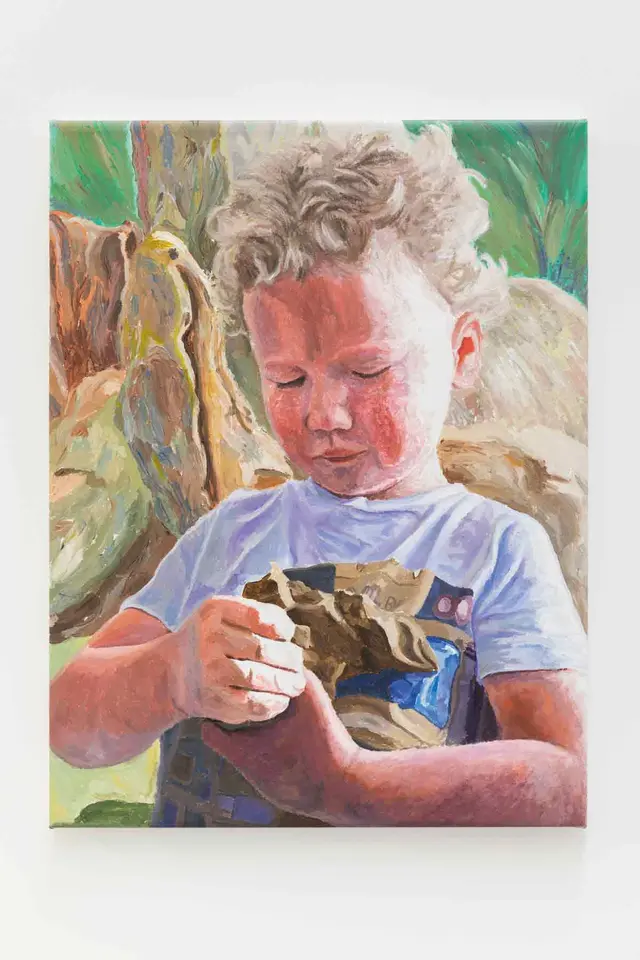

Given the historical prevalence of artists using technology to depict friends, scepticism around Hypersentimental Art is both natural and necessary. The trend is rooted in Sentimental Art, which is characterised by depictions of innocence, beauty and romance, often featuring themes like nostalgia and melancholy. These idealised portrayals are often enhanced by soft lighting and associated with gendered and infantilising words like “sweet,” “cute,” “lovely” and “pretty”. Sentimental Art has long been criticised for its avoidance of darker aspects of existence, a strategy which has been seen to sustain inauthentic illusions and ideologies.

While there is nothing particularly wrong with embracing the sentimental, the reasoning behind a revival should be more rigorous. Hypersentimentalism might be presented as a response to the decline of influencer culture on platforms like Instagram, yet it employs similar rhetoric, imprudently drawing from politically fraught pre-social media (therefore pre-BLM) and late 2000s aesthetics to nurture curated nostalgia. There is a blind spot in this optimistic shift away from polished online marketing towards trends like nano-influencing or “de-influencing.” This cliqued perspective omits its own inherent imperfections by willfully posturing virginally uncritical elitism.

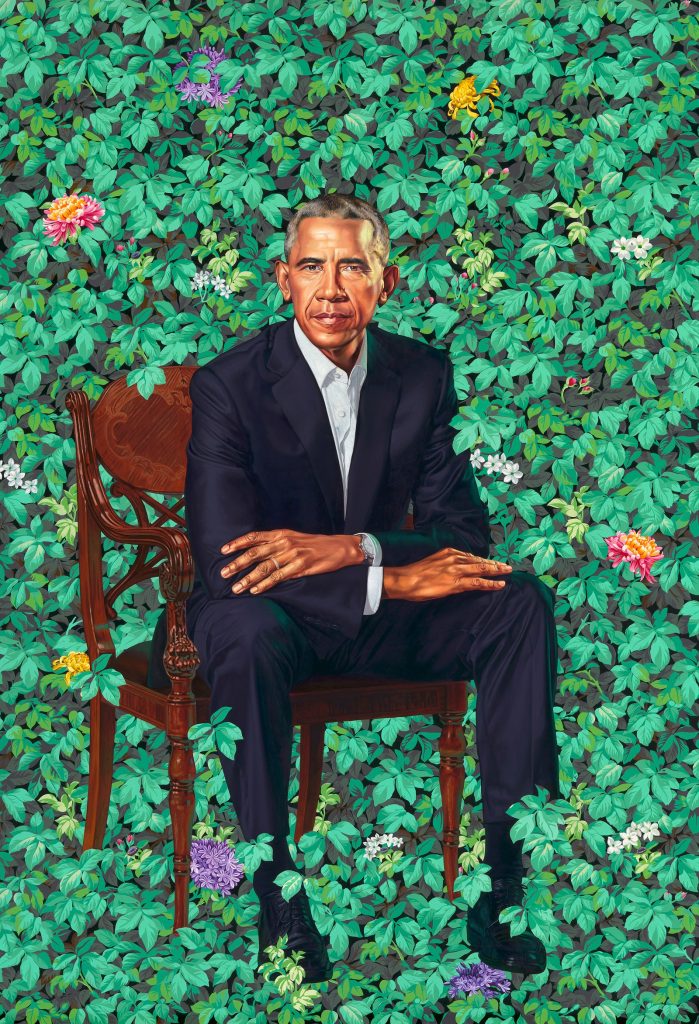

Like the long lineage to which it is yoked, Brown’s Hypersentimentalism revolves primarily around New York and Berlin and during the podcast, she boldly contextualised the trend as a response to the fatigue from the hyper-visibility of political and identity-focused art. While this excludes artists without the privilege to tout political or visibility fatigue as a justification for purely sentimental pursuits, she still has no qualms naming political and identity-centred art like Somali-Australian artist Hamishi Farah’s Representation of Arlo (2018), a response to Dana Schutz’s controversial painting Open Casket (2016), and Kehinde Wiley’s portrayal of Barack Obama (2018) as part of the trend, which is cause for concern.

The tokenism is blinding and using these examples comes off as a thinly veiled attempt to add colour to an otherwise colourless domain. While citing artists like Farah, Wiley and Salman Toor, Brown’s geographically and nano-influencer-specific iterations of Hypersentimentalism feature predominantly white figures, making the trend appear to leverage fatigue (dare I say — [white] fragility) to subvert the influence of subaltern portraiture trends, thus restricting innovation to the confines of the Western art world’s tenaciously negligent nexus.

Brown’s audacious attempt to make affluent, Western artists and their inner circles trendy through the use of ‘vibe shift’ or ‘IYKYK’ (if you know, you know) logic, hijacked from popular online culture, is insufficient at best, considering the glaring gap between museum programming, art theory and active spaces of cultural production. Hypersentimentalism’s use of so-called “intelligent double speak” to spotlight New York or Berlin-based micro-celebrities in the art world, condescendingly and uncritically rushes to re-introduce cultural elitism to the realm of portraiture, ostensively mere moments after inclusivity became prominent in the discourse.

This story is produced in the context of an editorial residency supported by Pro Helvetia Johannesburg, the Swiss Arts Council