A couple of years ago, I wandered through the quite obviously constructed industrial showroom of a high-end homeware store in Kramerville — an expansive space often sparsely filled with ludicrously expensive imported furniture pieces.

The grey walls littered with drab black and white wildlife photography and commercially clinical Keith Haring and Picasso prints.

Meandering up to the top floor, which houses local and continental pieces, my attention was immediately grabbed by two artworks that seemed amusingly out of place. Two canvasses brimming with vibrant colours and unexpected source material.

Hanging there amongst a sea of greys and browns, were what seemed like film posters for Blade 2 and Terminator, the likenesses of Wesley Snipes and Arnold Schwarzenegger hand-painted onto enormous canvasses constructed from flour sacks stitched together.

The artworks were unique, yet, stylistically familiar — crafted in a visual language that populates Joburg CBD.

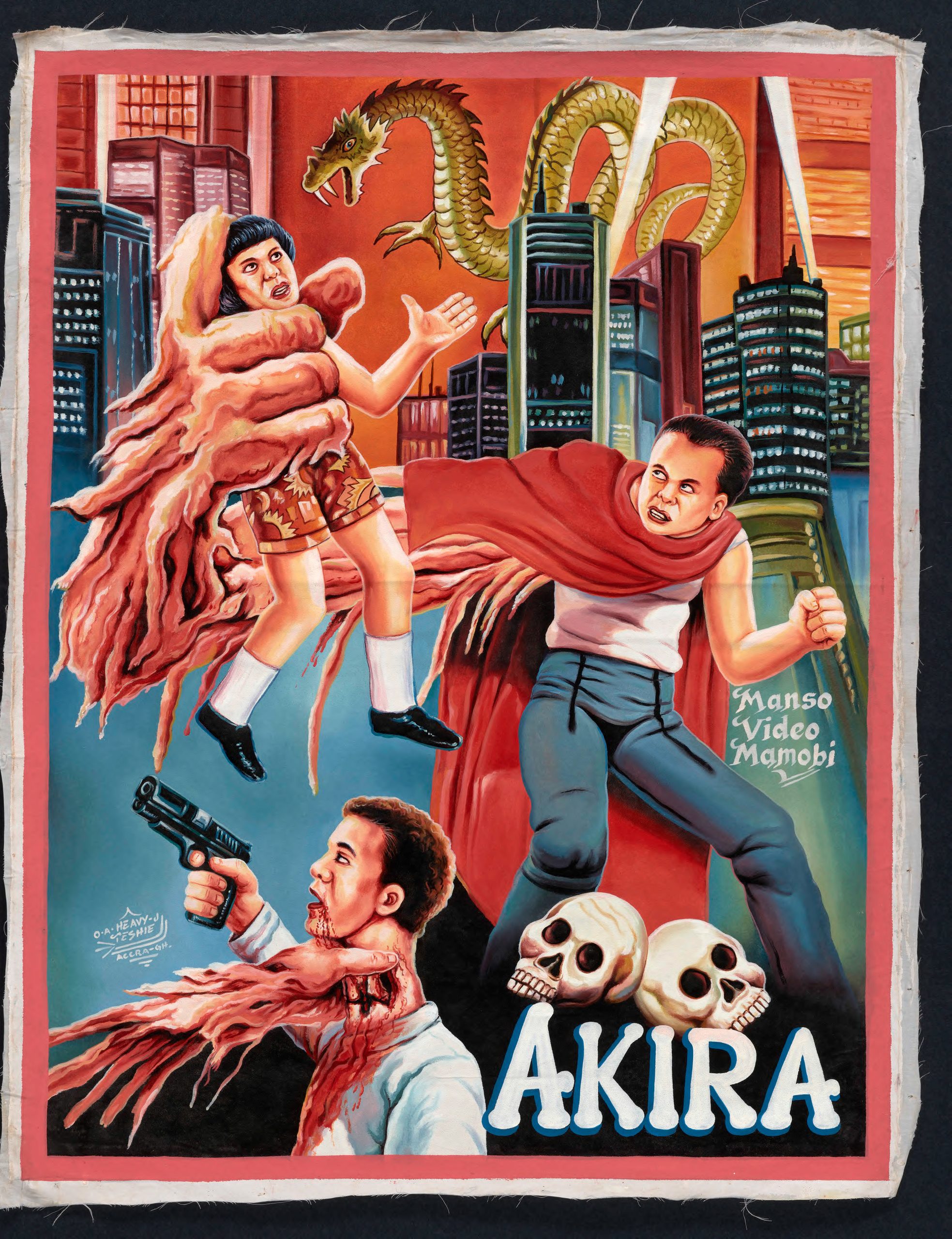

Heavy J, Akira, nd.

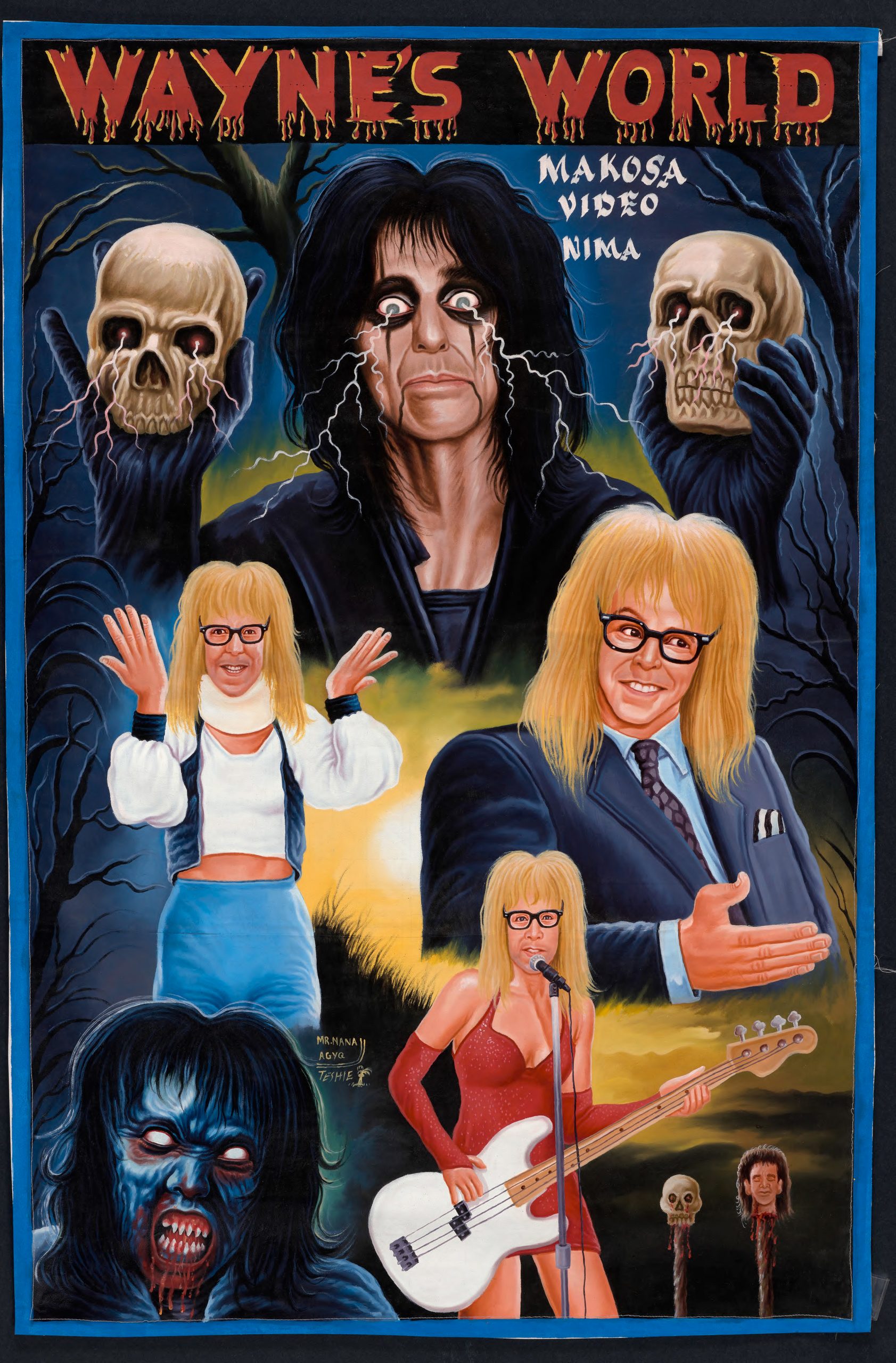

Mr Nana, Wayne’s World, nd.

“Place of Origin, Accra, Ghana”. This was my first exposure to the wonderful, often wacky and weird, world of Ghana’s hand-painted promotional material for films.

The portrait of one Mr Snipes in his all-black leather attire with a blood-soaked blade and half-headed vampire proudly hanging in my room was only part of the initial intrigue. Simply put, I had to know how and why these amazing pieces of art came about?

After a quick browse on the internet, I stumbled upon the Chicago-based Deadly Prey Gallery, co-founded by Brian Chankin and Robert Kofi.

Together, Chankin and Kofi aim not only to preserve and archive the incredible work produced during the golden era of these film posters/artworks but they also commission contemporary pieces by some of the legendary Ghanaian artists who pioneered this style and new faces under the mentorship of the masterful artists who came before them.

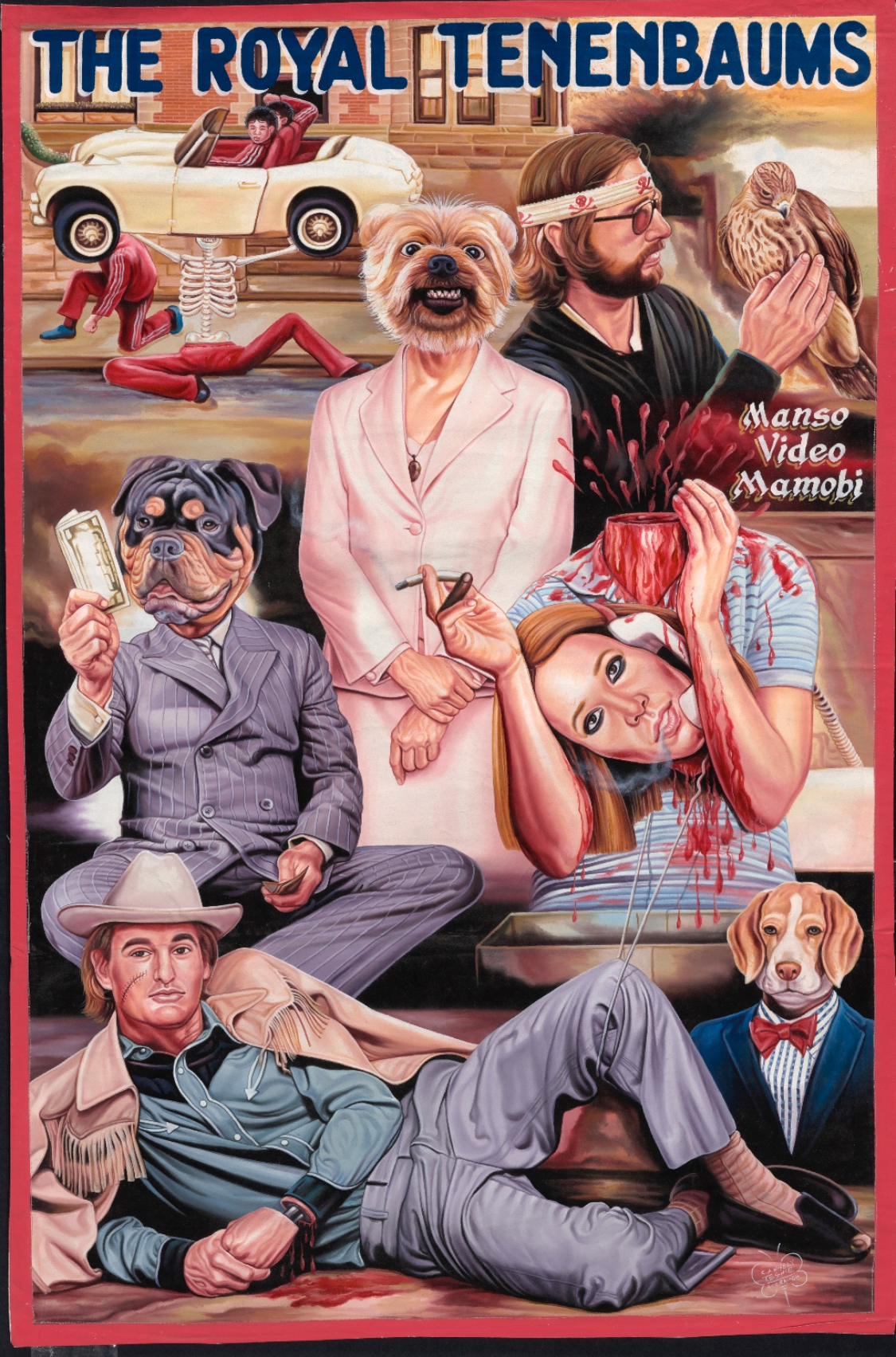

C.A. Wisely, The Royal Tenenbaums, nd.

The history surrounding the how and why these pieces of art came into existence, relates back to the popularity and success of mobile cinemas in Ghana between the 1980s until around the year 2000. Industrious entrepreneurs would lug around a VCR, a television or projector and a diesel generator in a truck, setting up makeshift screenings in villages across Ghana. As these mobile cinemas increased in popularity, so did the need for the entrepreneurs running them to distinguish their own offerings. This led to a trend of commissioning promotional film posters from local artists, predominantly sign painters. I found Chankin’s insights on the origins of these artworks particularly interesting:

It’s important to know that most of the artists who became movie poster artists were first sign painters and continued to paint signs in their spare time. Normally, these signs were made for small businesses, the most popular being barber shops, beauty salons, grocery stands and pharmacy or herbal shops. To set that shop’s product apart, the artist would do their best to paint it in the most unique manner which is often [through] some type of abstraction.

Haircut signs are the easiest to relate the movie posters to. It’s normal to see floating scissors, clippers and seemingly random containers of ‘Sportin’ Waves’ in the scene amongst the actual haircut imagery. An artist might show six different styles of cut in one sign — each haircut named and titled on the sign — with the intent of the customer being able to choose their cut directly from the sign. Naturally, the most striking painting and slickest names would receive the most requests. If it was a portrait of an American star with a specific haircut, chances are it would be a popular choice.

Stoger working on a Pee Wees Big Adventure painting.

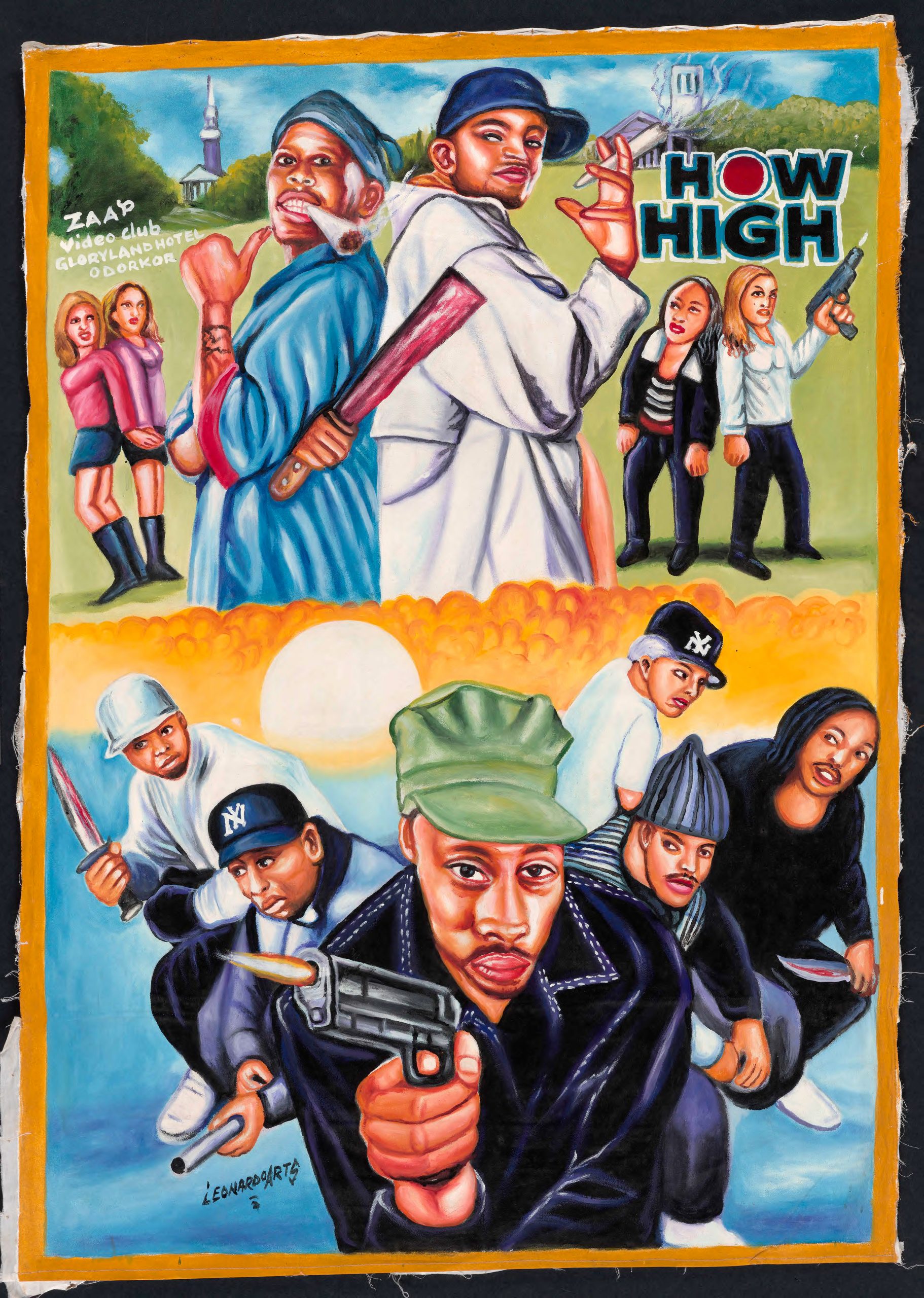

Leonardo, How High, nd.

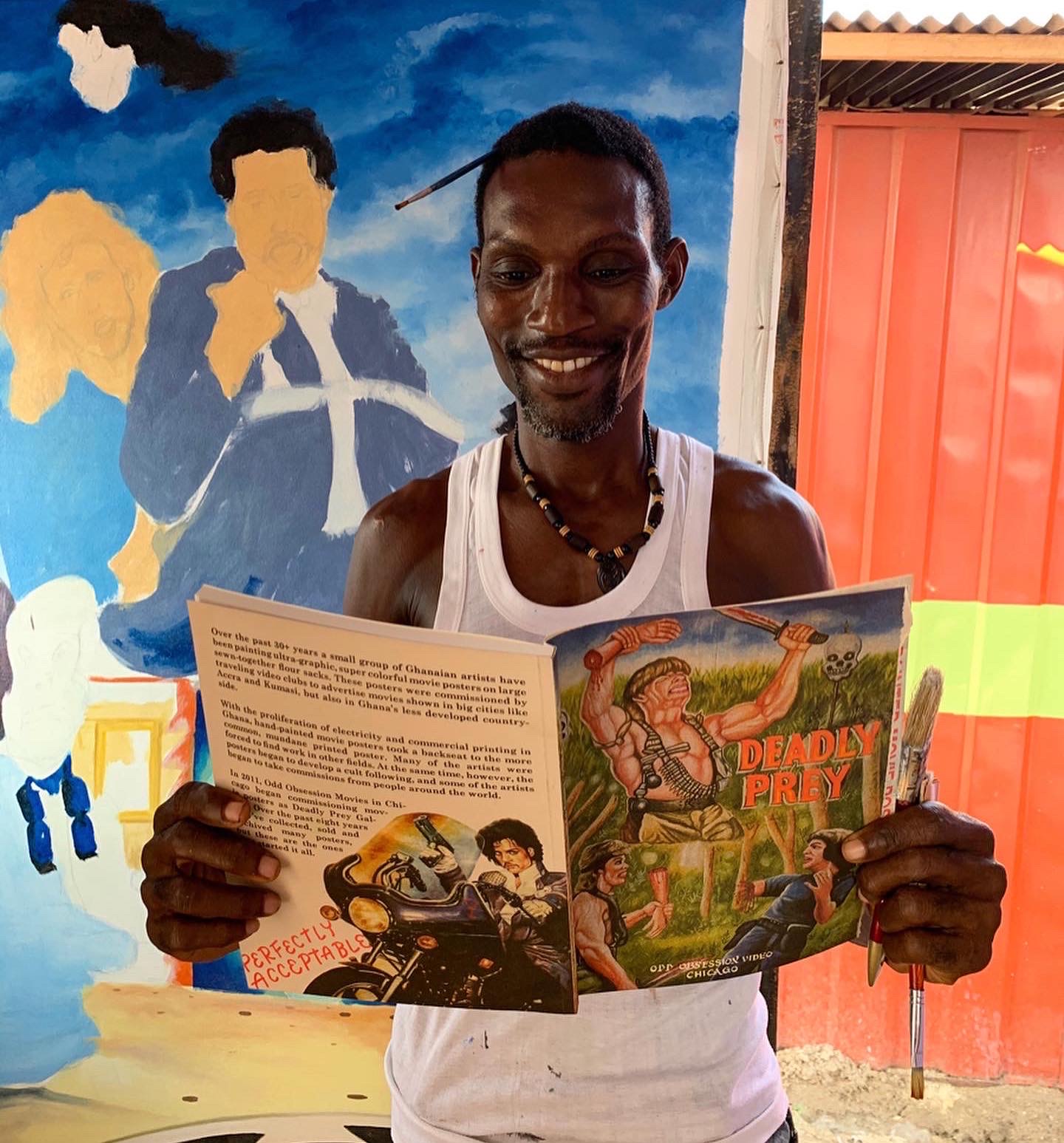

Stoger reading Deadly Prey.

I see so many different interpretations of the rapper Ludacris on signs outside barber shops in Accra still today. Now circling back to the movie posters, while seeing items in a haircut sign painting like creative renditions of scissors, pomade and hairstyles — might influence your decision-making process when partaking in the functional act of getting your hair cut — what might spark a patrons interest when choosing a leisure activity like which movie to watch?

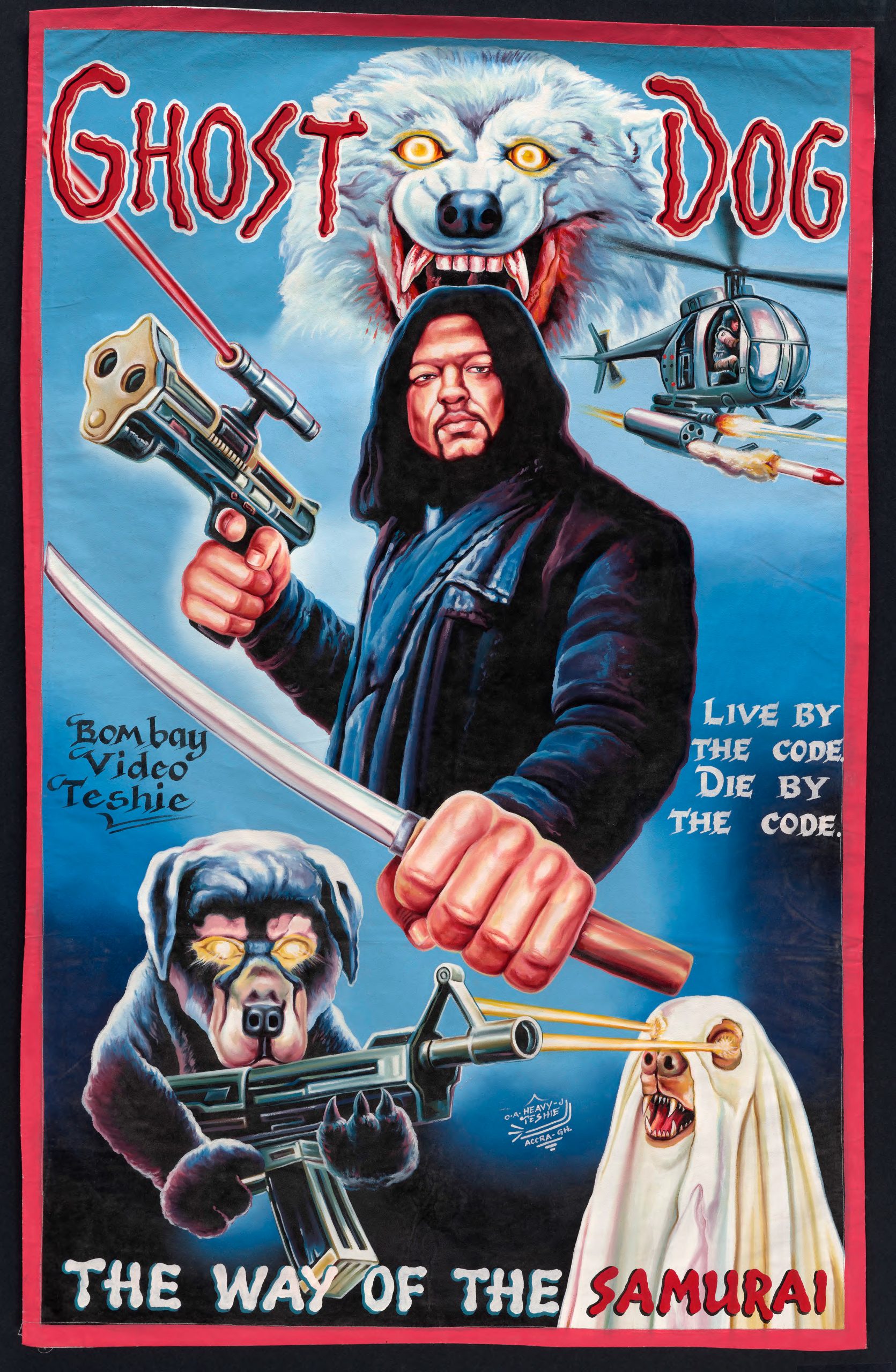

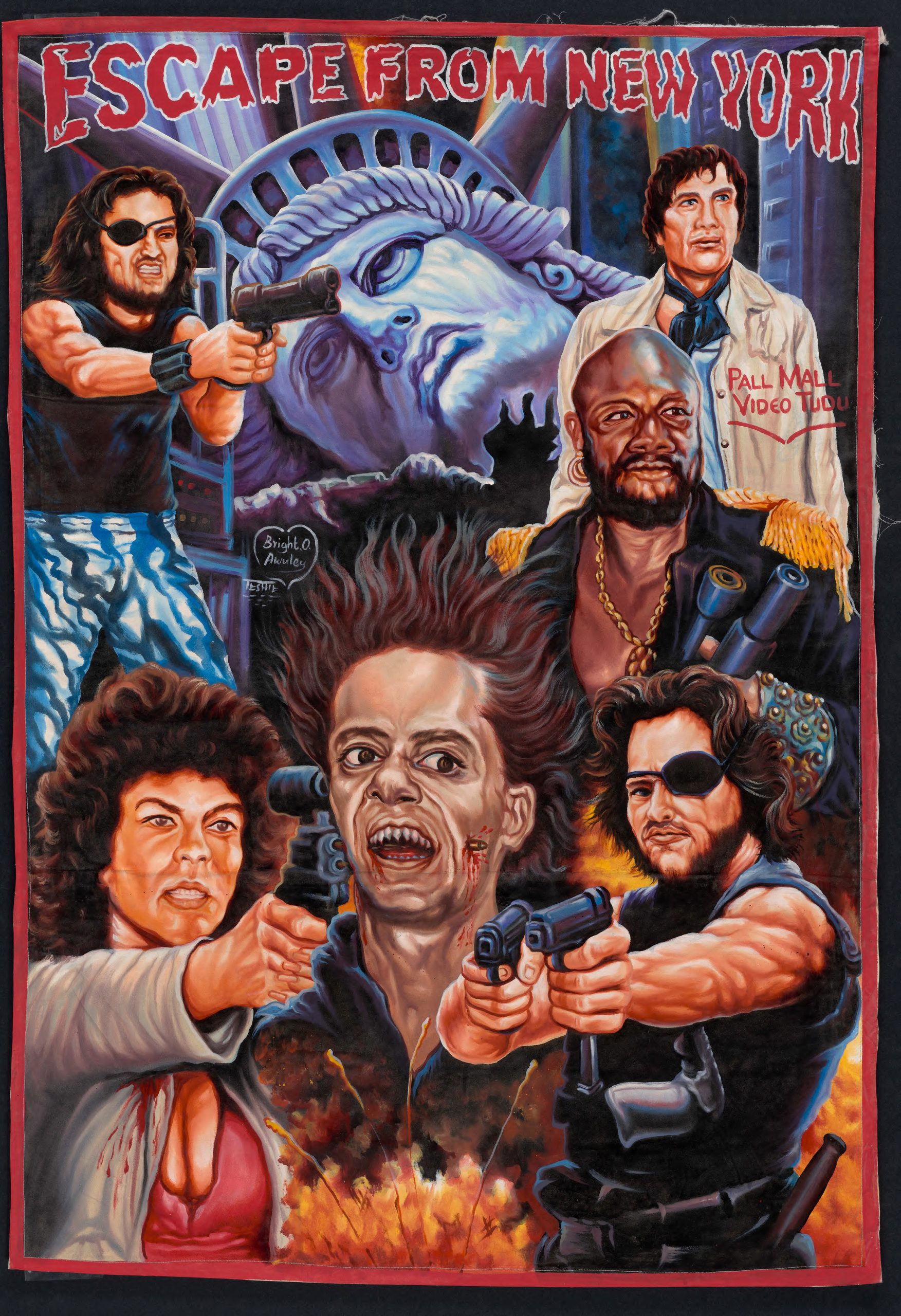

Looking at the movie posters made in Ghana from the ‘80s until the current day, it’s clear to see a combination of guns, skulls, demons, sex, snakes, violence, monsters, horror and/or a well-known star, whether it be Jean Claude Van Damme, Cynthia Rothrock, Jackie Chan, Arnold Schwartzenegger, Amitabh Bachchan, Nkiru Sylvanus or Saint Obi. The movie posters gave these same sign painters a newfound freedom of expression. The artists who became movie posters painters joined a fraternity that would become a very prestigious and serious profession.

Not just anyone could become a movie poster artist, you had to apprentice under a master artist for a number of years before you were official. Those who made movie posters without this apprenticeship were quickly dismissed. It was very serious then and continues to be very serious today. My partner, Kofi, works with each of the ten artists daily, I’d call him a modern-day video operator of sorts. Not coincidentally, Kofi worked in the Ghanaian mobile cinema as a teenager in the 90’s when many of these great artists were just starting to paint movie posters.

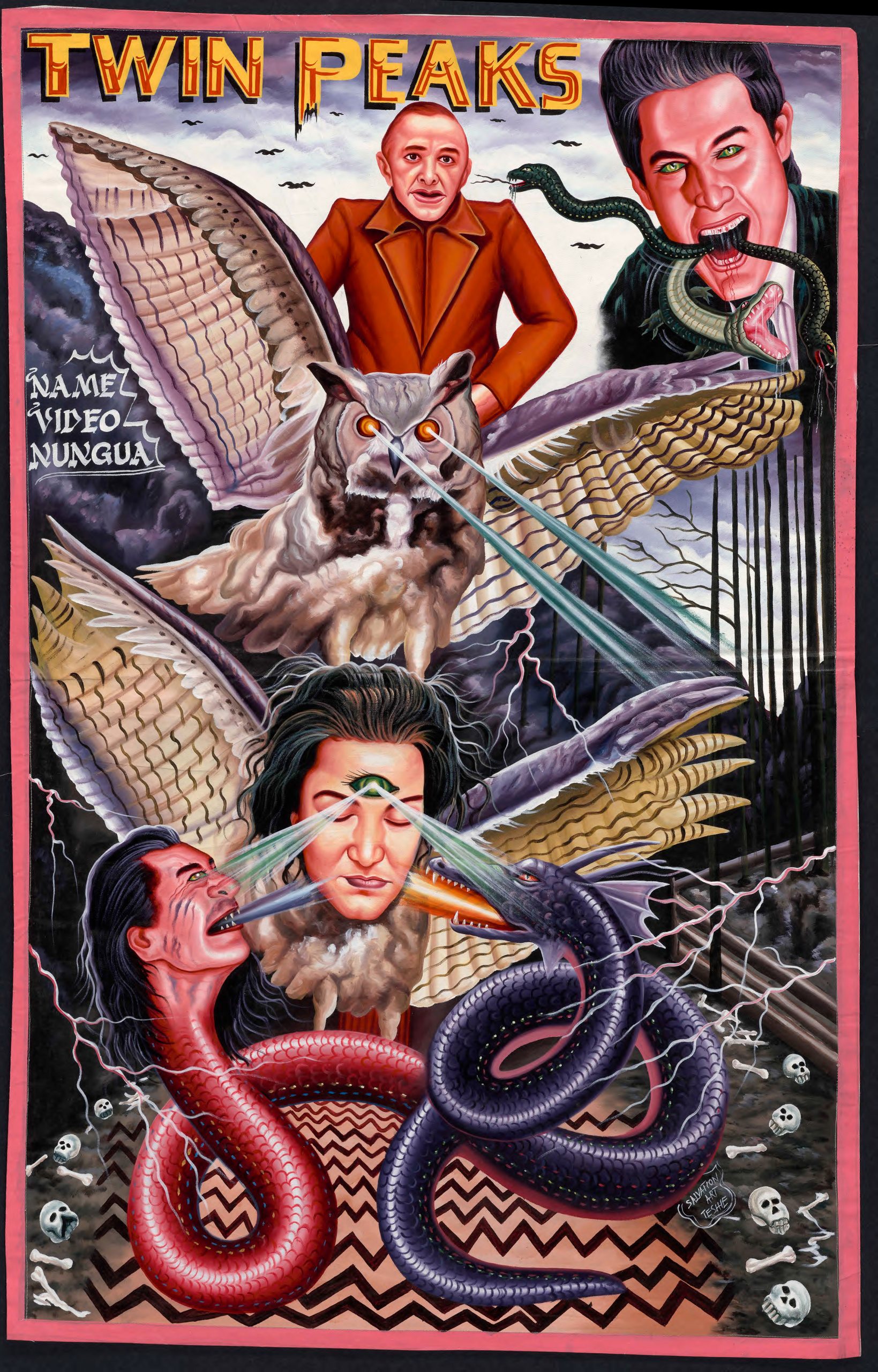

Salvation, Twin Peaks, nd.

Something that is evident throughout the works produced by these masterful artists is that regardless of subject matter — whether it be a Hollywood blockbuster, Bollywood musical or a locally produced film — the visual language present is by no means westernised.

Instead, it’s stylistically distinguishable, creating a particularly Ghanaian interpretation of these films and characters. The difficulties of creating your own distinct visual language — away from the clutches of an ever-present American cultural influence — is something I discussed in depth with Garth Walker, the founder of South Africa cult design magazine iJusi.

Chankin, however, has some ideas on how the artists circumvented this pitfall.

Heavy J, Ghost Dog, nd.

Bright Obeng, Escape from New York, nd.

Even though a particular movie being called upon to paint may be from Hollywood, I think [that] this visual language within each painting, maintains itself in part because of the presence of each video club’s video operator. The video operator not only chose and directed each title for the artist to paint but would explain which characters and items to include and provide descriptions of those characters and items, oftentimes without any printed reference or [with] very little printed reference.

Even if the movie being promoted was not from Ghana, its overall feel couldn’t help but be distinctly Ghanaian. It’s important to mention that it’s not just Hollywood movies that were popular during the mobile cinema days in Ghana, but [so were] Bollywood musicals and movies, martial arts and action movies from Hong Kong and China, as well as native West African movies from Nigeria and Ghana.

The golden age of mobile cinemas has long since passed, however, interest in contemporary work has exploded over the past few years. Given our great continent’s long and storied past with exploitation and appropriation — not only of land but also of art, by the global north and traditional colonial powers — I approached the operations of Deadly Prey Gallery with some reservations and scepticism. Was this another case of African artists getting exploited to satiate the global north’s desire for the “exotic” or is it a sincere attempt to educate, archive and showcase these amazing artworks to the world?

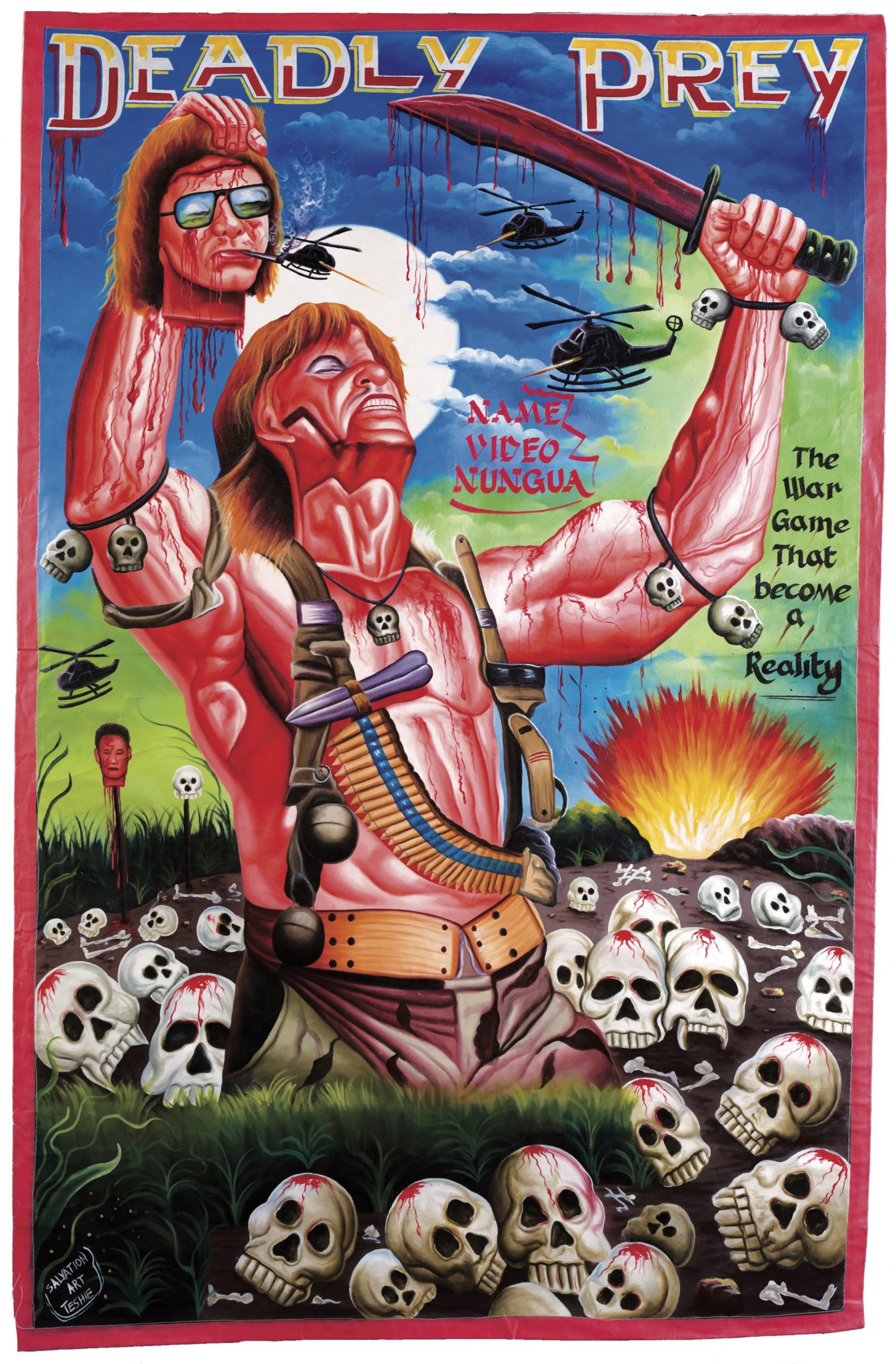

Salvation, Deadly Prey, nd.

Chankin welcomed these challenging examinations, as he explained that any potential reservations were highly justified in the larger art sphere. However, I’d like it to be stated clearly that Chankin and Kofi definitely distance themselves and their gallery from the ever-present predators within the art world. Not only do the artists make money from commissioned paintings, but Chankin and Kofi have gone the extra mile to ensure that artists receive their rightful rewards:

It’s been a long road getting to the point we are at. The artists have been exploited in the past by international as well as local dealers, so we’ve made moves to make sure that never happens again. By making sure we archive each painting with a great hi-res image, it’s given us the ability to make prints of their works and get them extra money after the fact. 100% of profits from this merch goes to them. It sounds simple, but it’s been huge for the artists to get that extra cash every couple of weeks, and it’s helped us earn their trust over the years with positive actions.

There’s a fine line between appreciation and appropriation. I hate the word “gallery”, and if Kofi and I could figure out a way to better explain in one phrase that our project revolves around art and artists, the word wouldn’t be used. There’s a brutal history of galleries exploiting artists — especially in the arena of what’s considered “tribal art” or “folk art”. People’s fascination with that notion of “exotic” has empowered galleries to present African art as mysterious and unattainable.

The illusion is that due to the gallery’s prestigious know-how, they’ve unearthed artwork that otherwise may not have been discovered. In actuality, they’re paying the artists dirt cheap prices or acquiring the work second hand and raising the prices exponentially. Meanwhile, the actual artist gets very little recognition, let alone a percentage of sales. This type of thing continues to be even a bigger problem of course outside of the art world!

These same problems are what has motivated us to be different. I come from the background of running a mildly successful, though historically relevant — I like to think — video store for almost 20 years in Chicago. My fascination with the posters from Ghana derived from my love of movies and movie poster art in general. I always considered myself an archivist and librarian above all else.

Farkira at his studio in Teshie.

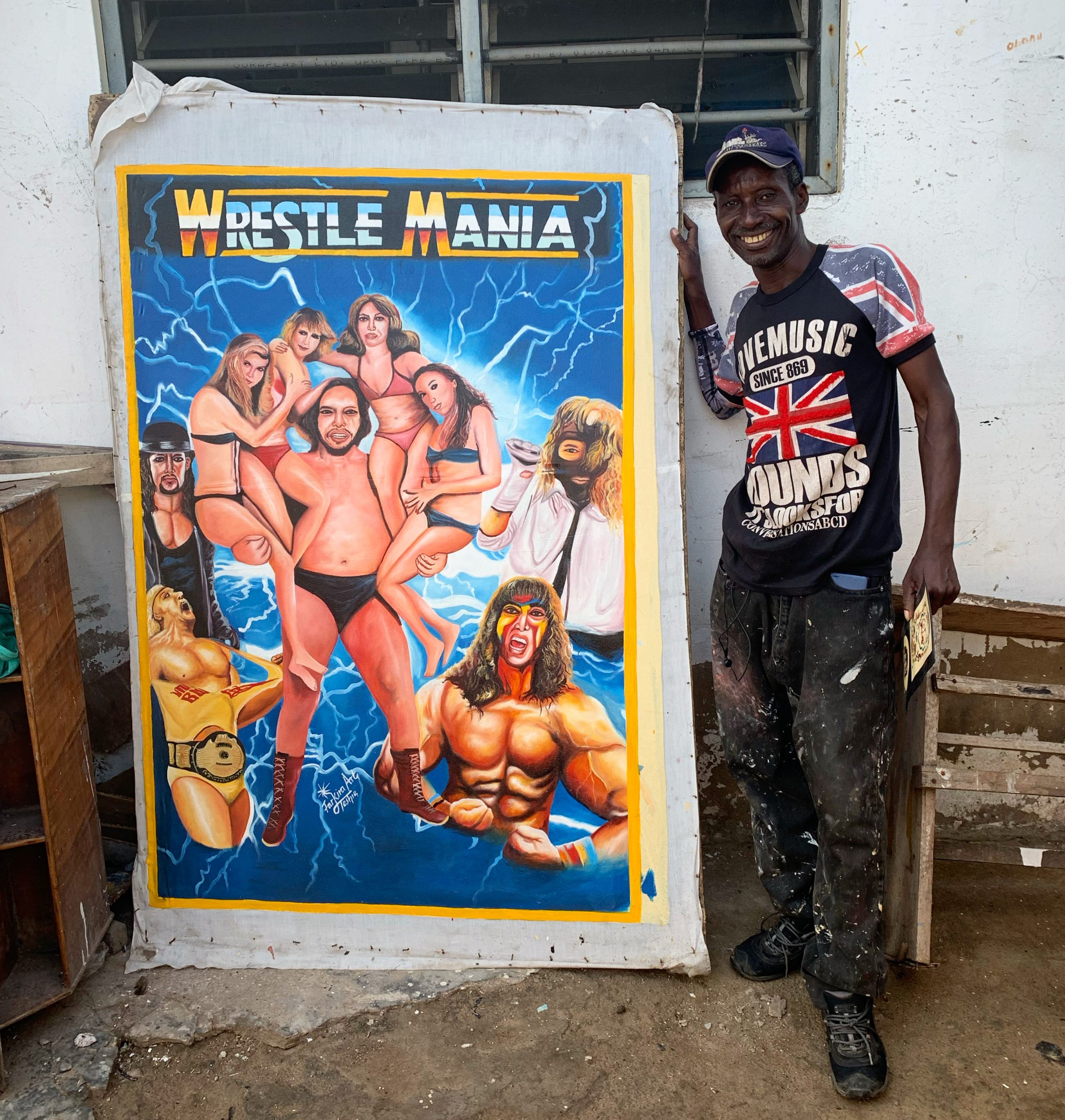

Farkira with his Wrestlemania painting.

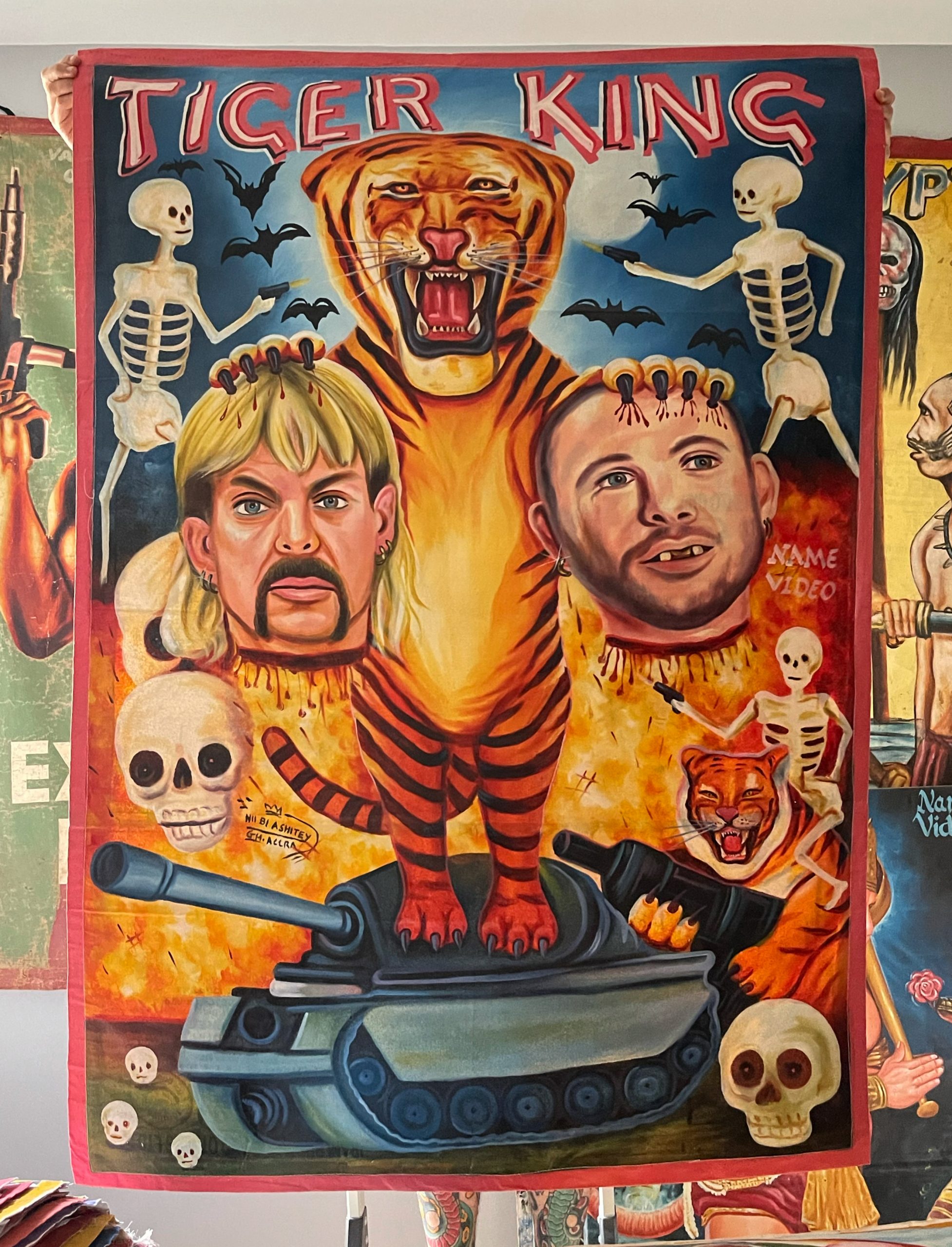

Nii Bi Ashitey, Tiger King, nd.

Heavy J with Kill Bill painting.