Neoliberalism and all his children, such as The American Dream and all its variations, would have many Black African artists spending their nights conjuring up dreams of achieving excellence via Western standards.

In line with a culture of celebrating and uplifting our people, we would cheer on when one of our own local artists is able to “breakout” into those newer markets. For that reason, it’s day of good news when Lulama Wolf has her first solo exhibition in the UK.

But what makes it most interesting is how Wolf’s subject matter, in this new space, seems to be a return to something familiar, something with deeper history than the present moment.

I come from someplace, I disappear to some place.

Wolf’s show was exhibited at SoShiro gallery in London, which houses artists from across the world. The show is titled Ndizalwe nge ngubo emhlophe (I was born wrapped in a white blanket).

Immediately, the title is a moment of reflection on Wolf’s part, contemplating one’s very entry into the world she explores today. It almost brings about an immediate sense of peace, thinking of the tenderness associated with childbirth.

In the context of Nguni spiritual proverbs, it refers to a baby born in an amniotic sack and how that it is, as a child, pre-determined to being spiritually gifted.

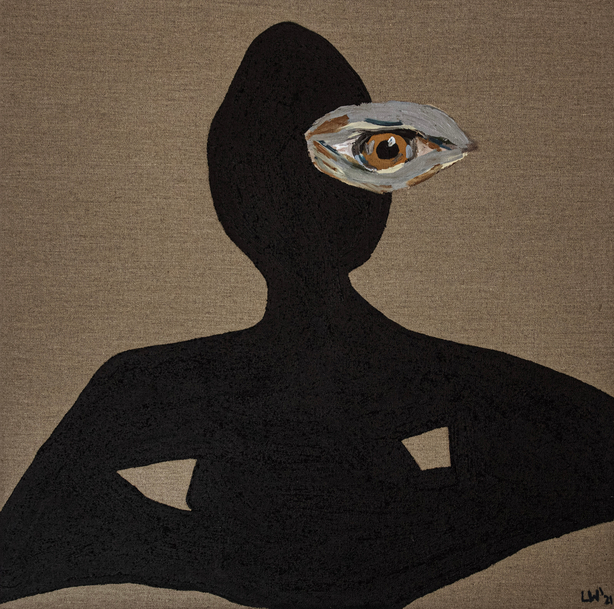

Umthati uyawuzala umlotho (I take the rough with the smooth), 2021.

However, the images themselves bring about something else to ponder. Not necessarily the opposite of that – but something not easily placed in the realm of the familiar, especially in a western art context.

She defamiliarises the viewer through subjects which resemble a humanness but seem to escape it in the ways in which they twist and contort their bodies. They evade the physical and social constructs which bound us in our everyday lives, by placing them in voids of Autumnal colour.

If it isn’t that they are evading humanness, it could be that they struggle to achieve the right steps in the right sequence to perform it in the way it is expected to be. Or perhaps, they fear humanity – in the same way that even grown, right-step-right-performance having adults do.

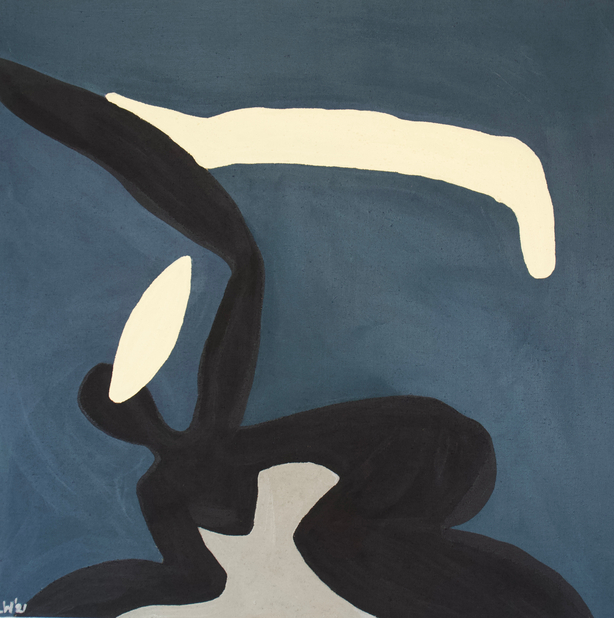

Sawa ngamadolo (We came to our knees), 2021.

The exploration comes from Wolf’s ever developing relationship with African spirituality and ancestors.

It’s an interesting parallel that she draws by making the figures crawl up in foetal position (and thus strengthening the pieces’ paediatric tie) – also acting as a homage to her ancestry.

What might the relationship be between those who have yet to roam the earth and those who roamed it long before? The works seem to be loaded with a silence, in their minimal figures, and allowing the viewer to feel something.

Beside emotional feel, the tactile feel of the show cannot be overstated.

“The paintings were intentional in the use of fabric as a tool to communicate an introspective issue that fuses itself into a broader concept of acceptance,” an official post on Wolf’s page read.

The works were multimedia through the use of a number of tactile, which acted as vital parts of the work on their own. In so doing, she transcends not just visual and tactile, but creates a work which inherently speaks to the aural.

Sijongene emonyeni (We are facing each other), 2021.

In this meeting of painting, tactile and the most familiar shapes and their most unfamiliar arrangements, Lulama Wolf brings together all of these things, and herself, into new spaces. She occupies the walls of SoShiro as nothing short of herself and delivers distinct and tasteful – the same style which brought her art to prominence.

The complexity of reminiscing something one hasn’t quite experienced, but is so deeply in tune to, is not a feat easily achieved – but achieved nonetheless by Lulama Wolf.

She speaks to the tired African experience, which is tired of the American dream, and tired of an uncomfortable, rest-deprived place in the world.

The beauty of existing in the same moment I, 2021.

Intlabathi ayixengeki nangamanzi (The crustiness of the sand is still embedded In murky waters), 2021.