Some stories don’t have a clear beginning or clear ending. Instead, they seem to be inextricable from the depth of the middle. That’s the case with Mbali Khoza’s Native of Nowhere, displaying at C H U R C H Projects in Cape Town. I had the pleasure of sitting down with her for an iced coffee and Earl Grey tea to discuss what she described as a series of interventions.

Native of Nowhere didn’t start with any great artistic gesture and daring prompt. Rather, if Khoza had to attribute the exploration to anything, it would be the moment several years ago when she first sat down to watch the film, Moonlight and thought, “Wow. This is beautiful.” It was in the way Barry Jenkins so beautifully and tenderly explored black male queerness; it was in the way Jenkins deeply embedded such rich emotions in colour.

She references this craft in her own work, as she returns to artistic practice, with the striking blue that overwhelms the C H U R C H Projects space for Native of Nowhere. This deep blue is how she chooses to step into the politics of traditional gallery spaces, but make the space her own liminal one. It isn’t so much decolonising the space, but a deep blue hue of her own, transitioning the space from more of a gallery to a living studio.

The idea of it being alive feeds into one of the major driving forces of the series, with that being black mobility. In this black mobility, Khoza says, “we keep coming back.”

“Having grown up with my mom, teaching me some aspects of being black in my culture – and when I say culture, I mean the spiritual, in isiZulu – she’d always spoken of this notion of spiritual mobility,” Khoza shares, reflecting on growing up as a black femme in Johannesburg. “But also a physical mobility. It’s this idea that I must be a version of one of my ancestors, or I look like one of my grandmothers. For me, it was this idea of, ‘how do we keep coming back?’”

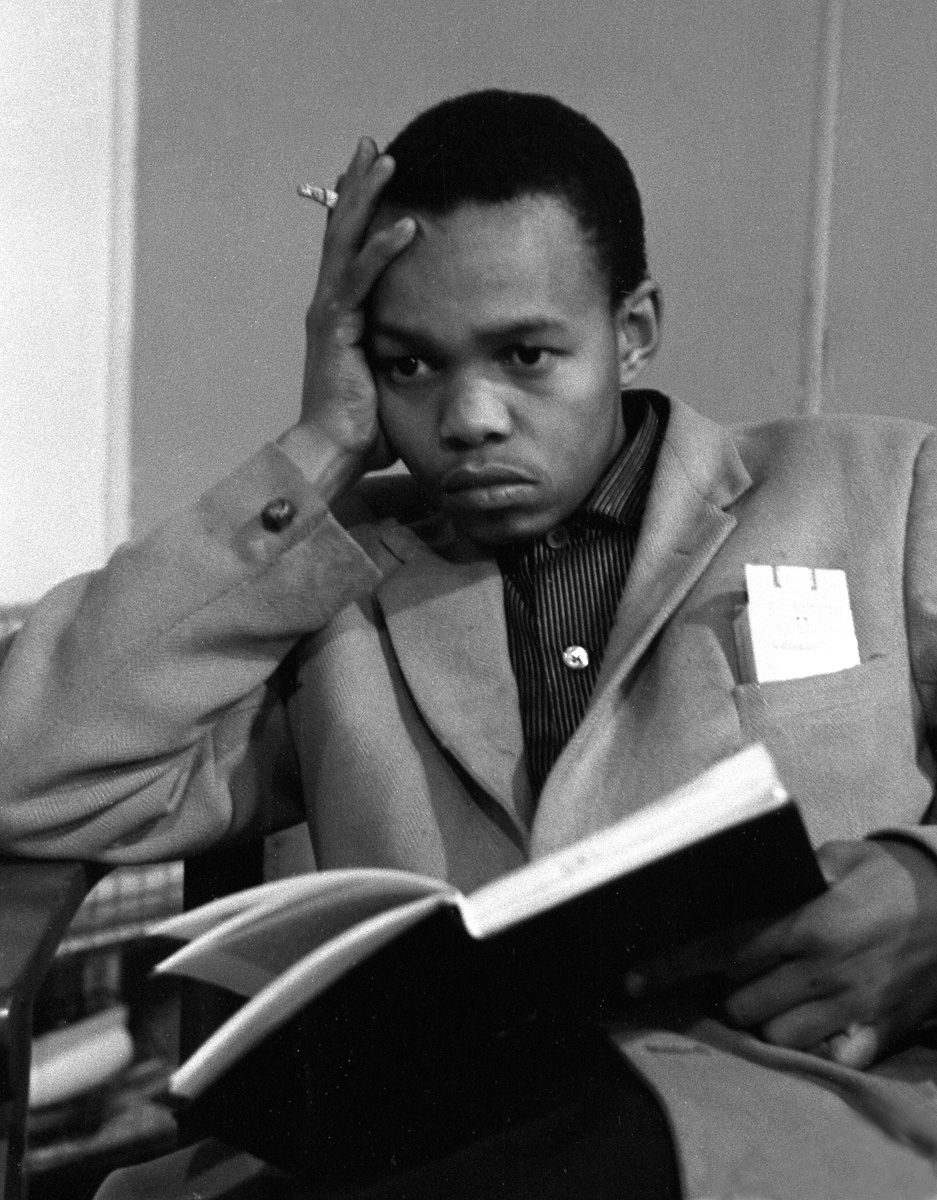

The question of ‘how’ here is a sincere one. Within a global context of blackness, Khoza acknowledges herself and others who have not been so easily able to hold onto language practices, for one. I suggested how isolating this can feel, this distance created by a number of external factors. These feelings don’t go unexplored in the intervention. Khoza draws from Nat Nakasa, whose work the intervention derives its namesake with short experts that explore the feelings of unbelonging within blackness.

“We’re moving to urban spaces, and no longer going back home,” she shared with me. “But I do think there are certain things worth preserving, and I do think language and land are of one those. […] We are using the English language to think about things which are natural concepts. The English language doesn’t encapsulate our experience.”

Photograph of Nat Nakasa

It’s an experience, complicated with moments of intense joy and intense trauma. Even that trauma begs to be asked, ‘How do we come back in a way that is sensitive?” For Khoza, this involved collecting the sounds of the ocean from Gorée Island, Senegal. These oceans, Khoza acknowledges, are the final resting place of so many black people, and are thus charged with spirituality. With these recordings, she comes back with a little piece of something so vast and so deep, without the need to unethically extract from the physical sand and waters. In light of this sound excerpt, which makes a soundscape for the scene of a ship which is situated upstairs in Church, it’s clear why Khoza struggles to say where the intervention started. It’s before us.

It’s referential. She references the water with this soundscape. With the bright blues of the walls, she references the waters that black African people have risked and continue to risk everything to escape home and find some kind of solace in the West. This is how her artistic practice works; Khoza doesn’t shy away from her role not just as an artist, but as a writer and academic. Referencing, and conversing with the texts she reads is a big part of her work. This allows her to explore an issue as multifaceted as identity and origin in equally multifaceted, visual, sonic and textual mediums.

“I think about [what it means to be umZulu] in my research. It’s a conversation I have with my friends. Especially as someone who is technically a suburban girl who has a very limited encounter with Zulu speaking people,” she says. “It’s either at home or at school. Much of the other spaces I navigate require me to speak other languages like Tswana, which I don’t mind because I have Tswana and Sotho people in my family. But I’ve never had that KZN Zulu “authenticity”. I don’t know what “authenticity” is because even the notion of Zuluness is created by Shaka Zulu himself. So it’s always a space where I’m reflecting on these identities I have.”

“Joburg will really complicate that, with the multiplicity of Joburg,” I say, acknowledging the struggles of holding onto one true “authentic” identity in metropolitan living.

“That’s what I enjoy about Joburg though,” Khoza explains. “We start to develop new ways to speak to each other, because we recognise we don’t all come from the same spaces. Joburg was a space itself that was created, by migrants, with different people coming in from all across the country. Not to say that there weren’t people there already,” she clarifies. But Joburg, as we have it today, is socially created.

I realise in this moment, a deeper layer of the work: if one can divorce themselves froma single idea of themselves, and wrestle with that, it disrupts the idea of existing within a monolith.

I ask then her thoughts on the notion of Heritage Day. As heritage month encourages, we begin to discuss the ideas about what has become of September 24th, and the notion that what we have now is a watered down idea of heritage, and less a celebration of cultural history, and more of what we know as a generic, rootless “Braai Day”.

Khoza is humoured by the idea, upon drawing on what the South African government defines heritage as. The definition, which is from 2013, doesn’t really seem to say much at all. “The thing that I’m struggling with is that the definition of heritage doesn’t really provide a ‘why’. I think that’s important because it’s a reflection of why our curriculums, all the way from primary school, all the way into high school and eventually university, are this way. Black people only start learning histories about themselves in a university space. From my experience, the ones in high school and primary school are glossed over, because of not wanting to engage a very important part of history which explains how we got to Post-Apartheid South Africa.”

“I know that on heritage day people are encouraged to wear their regalia that is representative of the community they come from or the community they identify with. That’s great! But how is this culture and heritage reflected in the curriculum, in a way that we can have actual pride in something we know? What do we know [from the curriculum] about Zuluness or Xhosaness or whatever it is that is worth celebrating? Or just Blackness, that is worth celebrating? In something that connects us all and in different spaces. I think what unites us all – and I hope this is the same for all Black people – is a shared kinship in the liberation of Black people.”

It’s Blackness celebrating and championing for itself that Khoza holds besides these institutions which have failed us – with the curriculum being just one example – that makes Khoza say that Heritage Day isn’t watered down, but “it was never really thought of in a critical way, really,” she says with a chuckle. A simple braai day is thus a fair reflection of the amount of intention and thought that went into the holiday. Without conversations of heritage tied to the land for black Africans – which the cited Chief Gboteyi writes about – how can it be a day genuinely embedded with meaning?

She also recognises that culture, in light of today’s youth exists in a beautifully complex way. With Black Twitter being a space for Black people across the globe to acknowledge their differences – with land perhaps not holding the same sentimental value for Black people in Europe for example – it also provides a space for Black people across the world to recognise similarity. Fallism here, Black Lives Matter there – something is shared, and conversations are ongoing about similarities, like hair. Hair is also explored within Native of Nowhere, noting that it historically and presently bares a spiritual meaning. “That’s a part of our culture as a people, all over the world!”

“What I think the youth have done is find connections with everything. Twitter has allowed them to find connections with people from other parts of the world, while also being critical,” she says. “It’s become a thinking space, a conversational space, a space of love, and a space of fun.”

Native of Nowhere, as a space, is equally charged with life. Khoza continuously pours herself into the space, moving things, removing things, and letting the space develop. In this way, it mirrors us, as people. Its physicality does not mean it exists in one way – it is fluid, moving through different phases. Native of Nowhere, contrary to what the title must suggest, is not necessarily trying to evoke a feeling of being dammed to perpetual lostness. It might be, with Khoza accepting many readings. But is neither (purely) this, nor (purely) that. It just is. It’s just like us.

Native of Nowhere is exhibiting until 31st August on 58 Church Street, Cape Town.