“To be pierced is to be attached, serving a purpose that hurts but binds.”

Reads the line accompanying Sahlah Davids’ body of work Pierced as it explores ideas of the artist’s cultural identity and the intersection between religion and politics. Pierced is a body of work distinct in many ways. To me, it stands as a reminder of my own cultural identity and allows me to question my own positionality towards the histories imposed on me. Art that makes one feel like their identity can be explored in poetic ways will always have a greater impact on me, Pierced provides such artwork. The most important thing art can do is allow us to feel recognised and Sahlah’s work does that for many people with Cape Muslim heritage, a heritage often sanitised or forgotten. Sahlah was inspired by the work of Gabeba Baderoon and Achmat Davids and their exploration of Cape Muslim history and heritage. She soon realised that there were so many experiences shared between people with similar histories and wanted to focus on creating a body of work that allows for an understanding of these aspects through art.

Often when we attempt to think through the layered nuances of our existence we grapple with notions that at times put us through existentialism. However, through works such as those forming Pierced, we come closer to expressing and answering questions surrounding identity. The knowledge I was able to gain through engaging with the works by Sahlah allowed me to come to terms with my own personal history. Malayism as theorised by Achmet Davids is visually articulated well through Sahlah’s work and brought me that much closer to understanding the histories which inform my identity. Through the works having underlying themes of exploring Cape Muslim identity, I was made aware of a discourse that I had been living through, and often grappling with, my entire life. Engaging with Pierced, I began thinking about language, symbols and traditions unique to Cape Muslim people, as well as recognise that holding onto these unique to The Cape – continued by my own familial history – stand as an act of resistance to the Apartheid and colonial systems. In the way in which this creates its own discourse, Sahlah through her art creates a visual discourse surrounding Cape Muslim people, rendering questions we have surrounding our traditions and histories.

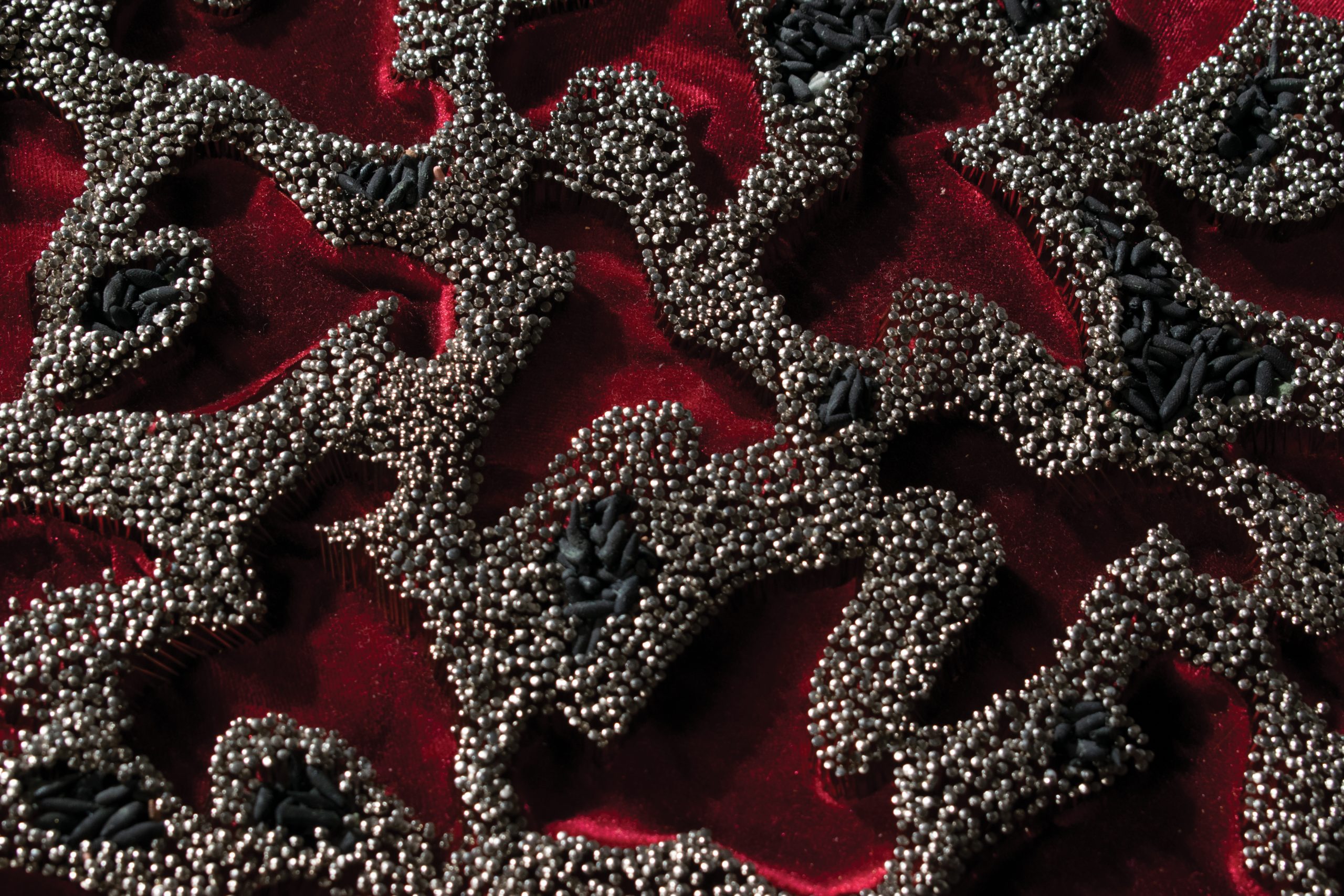

Visually the works which make up Pierced evoke a sense of violence in their rich colour and material, however, they also appear to create a sense of harmony between concept and material, appearing alluring through their embellishment. This is symbolic in thinking about how Sahlah creates work not as a negation of her upbringing but rather as a seeking of understanding and empathy. The use of pins in the cushions of the chairs rendering them uncomfortable to sit on serves as a metaphor to how we, too now, face an often uncomfortable past. Their decorative nature also speaking to the fact that often we find ourselves looking at Islam in South Africa from a very surface level approach, forgetting the long history it has had informing the histories of the country.

I caught up with Sahlah to speak about Pierced and the nuances of identity, art and politics. Below is our rich conversation:

How has your artistic practice changed or evolved over time?

Sahlah Davids: I always had an interest in understanding my Cape Muslim identity and how religion and politics intersected, and as a result, created its own traditions and rituals. The question I often asked myself was, why? Why are we doing this? What is the reason? And I felt I couldn’t ask those questions openly. I proposed these questions through my art practice. In my second year at Michaelis, I had a keen focus on Muslim Youth creating a safe space for conversation and integration. It was a place where we could understand and relate to the struggles, triumphs, and questions we had growing up. Existing in that duality — push and pull — between our traditions and secular world and our journey through that. That really began a springboard into moving my conceptual research into aspects of the Cape Muslim community and how this has been deeply affected by colonialism and the apartheid regime. How do we navigate this in a post-apartheid South Africa? Not to claim victim to the trauma, but take ownership and power of our existence within a South African society. It’s still a journey, and there’s so much to learn along the way. It was a way of understanding my positionality and understanding that the Cape Muslim practices are so unique to The Cape. This is how I began to work with fabrics, beads and pins. It was a way of connecting to my grandparents’ profession, but also how that profession exists due to a colonial past, and that process of continuing that profession as an act of resistance against those colonial forces. I work within concepts of a domestic space, home, community, and identity- this is signified through the chairs that are familiar and found within the homes of family members. I wanted to incorporate those viewing Pierced and engage with the work through familiar objects, [and think] “My ma has a similar chair” or “this fabric reminds me of something that I have at home.”

As your work centres around cultural identity, I am interested in finding out which parts of your own cultural identity do you believe have been shaped through the histories imposed on you?

Sahlah Davids: I think the parts of my own cultural identity [which have] shaped me are the stories told to me by my grandparents of place and placeless-ness. The rituals and aspects of community that are somewhat ingrained through tradition have become something I began to dissect, not as a negation of it, but as a way of trying to understand aspects of community and identity. I think something I strived to unlearn is the term, “Cape Malay”. I think a very important aspect of my practice and research and why I chose to really unpack aspects of culture and identity, was due to the many misconceptions of what it means to be Cape Muslim or to grow up within a community. We are not defined by these aspects, but for me, it was about delving into that history because that history, the perseverance [of] my parents, grandparents, and of my ancestors is the reason why I am here today.

I really enjoy your work as I feel as though it is a strong material articulation of the things you aim to communicate. I also gathered that the materials you used are chosen with a clear intention. Could you expand on this intentionality and why it was important using these materials?

Sahlah Davids: The materials I used had a strong intention to them. They were really inspired by the materials my grandmother would use as a seamstress; the fabrics, beads, pearls and pins. The chair itself is a reminder of domestic space. Every bead and fold of fabric is attached using pins and this, for me, was that process my grandmother would use before beginning to sew. It was also important for me to explore the visual language and aesthetics seen within the Cape Muslim community. The garments we wear, the way our cakes are embellished and even down to the way the Boeka Treats cookbooks have been curated. There’s a strong sense of colour and vibrancy that is both beautiful and intense. This is completely subverted when it’s connected to the chair, working with that idea of juxtaposition and duality. The chair also becomes a pin cushion, something that [can be] used. What was a truly remarkable experience was when I spoke to a wonderful aunty who came to view the Mashurah exhibition in Greatmore Studios. The aunty mentioned that the chairs reminded her of when she was younger. When they would find loose pins lying around, they would press them into the chairs as a way of storing them. It is these stories that are shared and really sparked my intention of using familiar objects. Pierced becomes both relatable visually and provides a space of conversation and instils that feeling represented through shared experiences and stories.

The discourse surrounding Malayism, as proposed in the writings of Achmat Davids, has largely influenced your work and conceptual approach. Why was this discourse so important to you and your practice?

Sahlah Davids: The reason why I had a keen focus on Malayism was due to the understanding of Cape Muslims as, throughout history, strong-willed and powerful individuals that resisted colonial forces. Malayism does not define the Cape Muslim community, it was due to the degradation of the Apartheid regime. But to understand aspects of identity is to see how these misunderstandings manifested and where they come from. Positionality is about understanding that duality, acknowledging the good and bad and striving to unlearn things that need to be unlearnt.

I never thought about traditions unique to The Cape standing as an act of resistance to colonialism. Do you see your work as a resistance towards a one minded outlook on religion and culture?

Sahlah Davids: In some ways yes! I do see Pierced as a way of acknowledging the intersection between religion and politics in forming unique traditions. When engaging with the conceptual ideas that sparked Pierced, I felt that there were so many aspects I didn’t know about, I was learning about my own community from the community and aspects of tradition. Achmat Davids’s work answered many of the questions I was afraid to ask. Maybe understanding and engaging is a form of resistance, it’s taking back the power [and] not being defined by colonial past or white authority. It’s taking ownership, acknowledging aspects of the past to spark change. Pierced stands as a form of resistance by the way it confronts the viewer and celebrates aspects of history and heritage by combatting misconceptions.

I find your work allows people to begin questioning their own positionality in relation to religion and culture. Through creating Pierced what was your intended outcome for viewers to experience or think upon?

Sahlah Davids: My intention was to create a space for conversation and awareness of community, culture, and tradition. There is a space for these concepts to be explored through art practice. It creates a visual archive of history and heritage pertaining to the Cape Muslim community. To understand where the term ‘Cape Malay’ comes from and why we need to question or challenge certain constructs. I think it also has a lot to do with representation, experiences and challenges that are valid and allow for the viewer to engage with something that is very rooted and innate in community and to celebrate who we are. I wanted the viewer to reflect on their own understanding of the body of work. For me, it was a form of introspection and I hope it allows the viewer to do the same.

I am interested in the many ways your cultural/ religious identity has shaped Pierced and also your journey as an artist. I know for me it was kind of a tough thing going to my family and saying “I want to be an artist” because of a particular hostility towards the art space, due to religious and cultural beliefs.

Sahlah Davids: You’re not alone! It was a hard choice and I felt that many didn’t understand the possibilities and interdisciplinary approach art usually has. In my third year, I reflected a lot on the figure and faith in art. I think that is another reason why Pierced manifested into more abstract forms. The chairs are accompanied by sounds of protest, dhikr, traditional lectures and prayer. It somewhat symbolises the intertwined nature of religion, politics, and culture. Pierced aims at having no bias or negation, and this manifests through materials used. In my experience, that hostility was rooted in misunderstanding as it brought about questions like, “how are you going to make money?” and it’s the assumption that art is for the elite and those who can afford [it]. This stems from the inequalities expressed through apartheid with the lack of equal opportunity for all racial groups. That was another reason why I wanted Pierced to be very relatable for individuals from the community. Art doesn’t solely belong on white-walled gallery spaces. Our great-grandparents, grandparents and parents were all artists. Dressmakers, carpenters, tailors, artisans. They had immense skill and craft that I admire deeply.

I think an interesting thing you bring up in your artist catalogue is stating that through Pierced you are not attempting to determine what is Islamic or un-Islamic but rather portray nuances of what it means to be Cape Muslim. I want to find out how you managed to engage with ideas so integral to a community without alienating yourself or your work from the community to which it speaks.

Sahlah Davids: Such an important question! A lot of it had to do with being in conversation with Muslim youth, family members and members of the community. Having just graduated and during the pandemic, it was something that I wanted members of the community to experience and feel represented [in]. I exhibited this body of work at Jaffer Modern at the beginning of the year [and] I had overheard someone who was viewing the exhibition say, “this is where we find ourselves… my grandmother is a seamstress too…I have this salaah mat at home… I have a book by Achmat Davids at home too.” This was an incredible experience.