What is a revolutionary act?

One that moves toward revolution? Towards the complete transformation of all that we know as our own certainties? The questioning of the unquestionable? The development of what has been forgotten — of what has been annulled?

Who is a revolutionary?

The one who subverts the determined concepts? The ones who broadcast with echoing voices through the forgotten streets? Are revolutionaries those who present or are they those who tell?

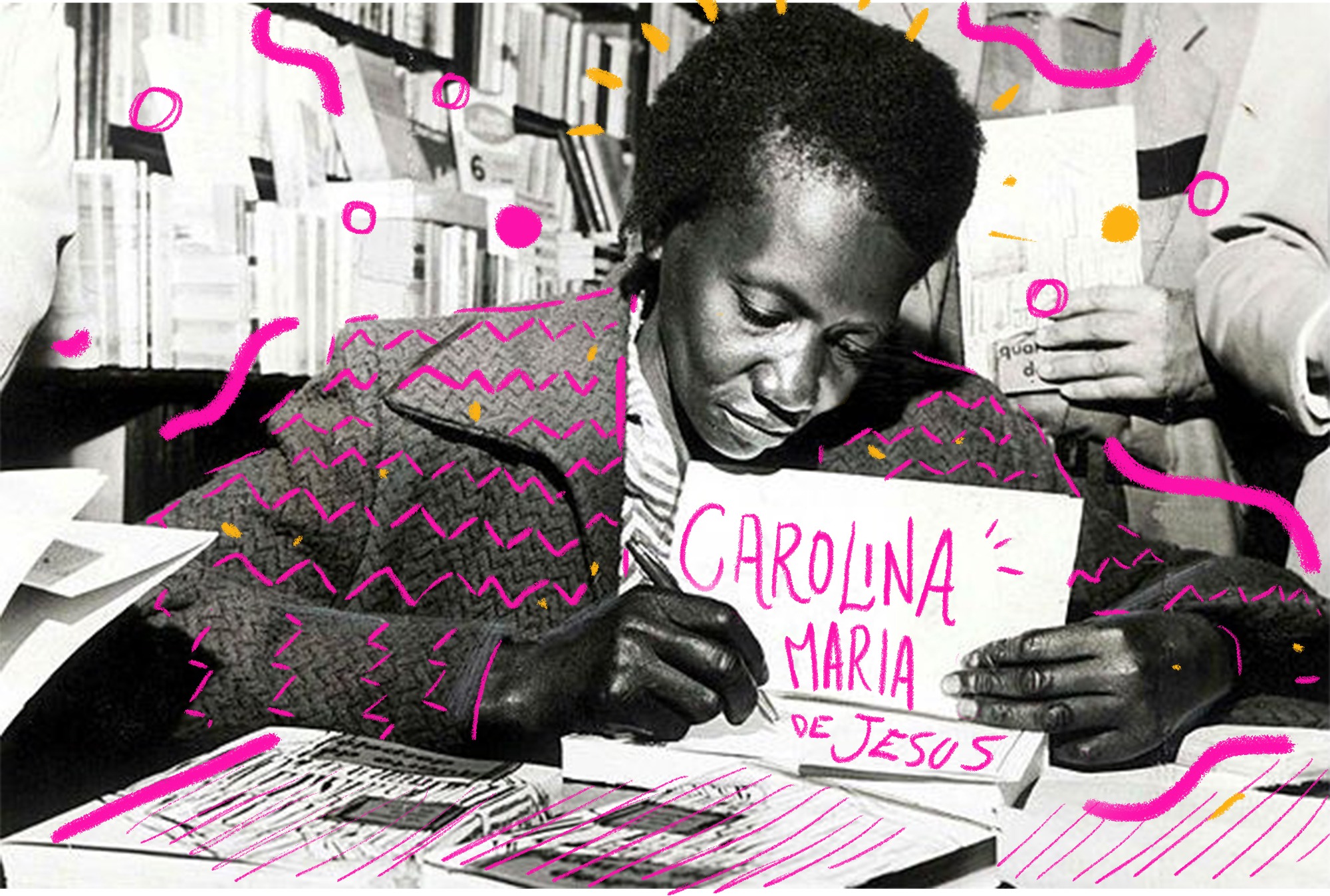

The truth is that I don’t know to what extent Carolina Maria de Jesus is a revolutionary. Author of the celebrated work Quarto de despejo, a diary that presents the life of a Black woman from the outskirts of Brazil.

The book deals with themes that are part of the backbone of Brazilian society: slavery, hunger, misery, ancestry, presence and absence.

The most recent Brazilian edition of Fanon’s book Peles Negras, Máscaras brancas (Black Skins, White Masks) has a preface by Grada Kilomba. In it, Kilomba engages with the principle of absence I’ve previously mentioned, as one of the fundamental bases of racism.

When something that exists becomes absent — there — white spaces are maintained and whiteness becomes the norm.

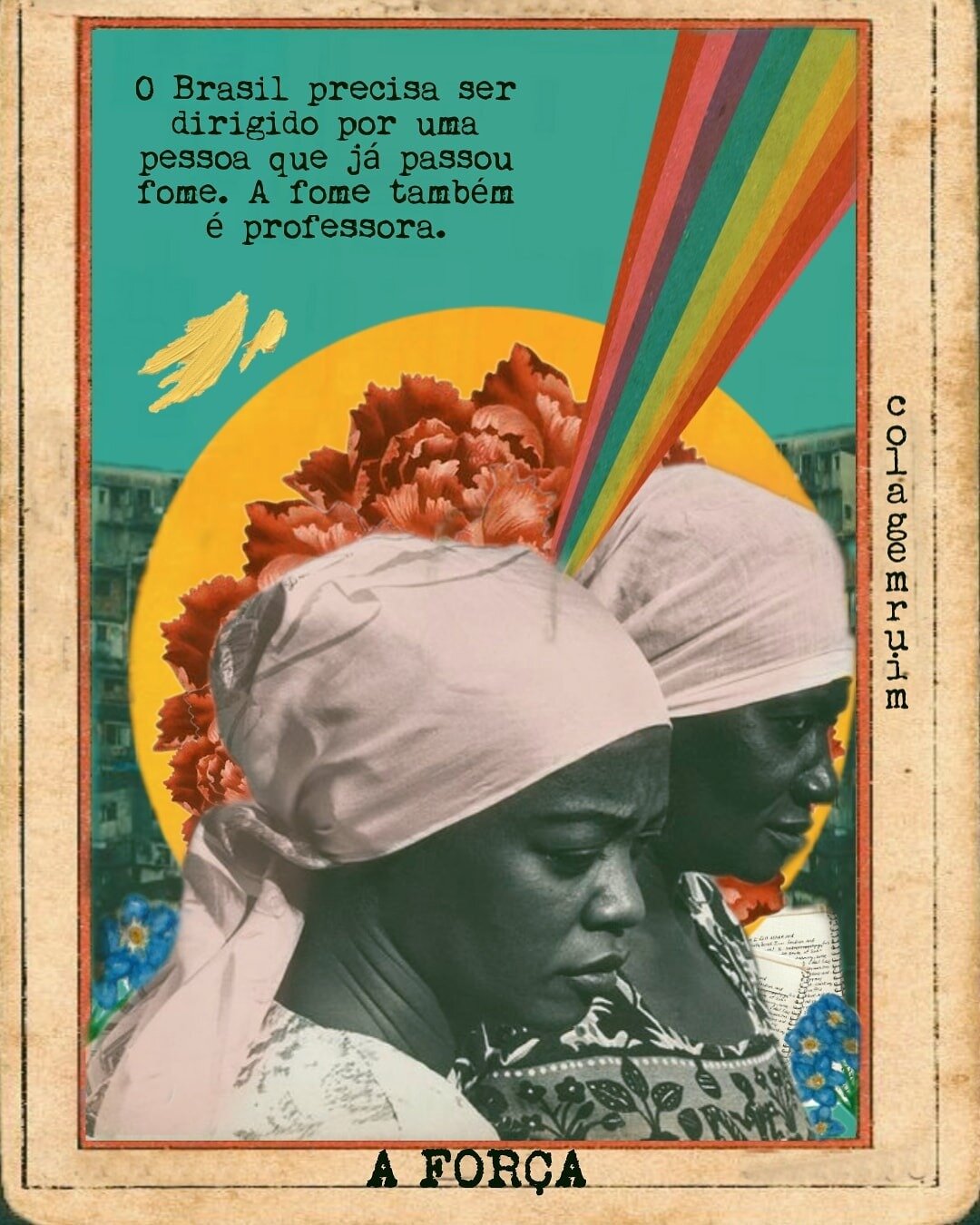

And with the preface conclusion, Kilomba reaffirms what is brought about through Maria Carolina de Jesus’ work; “to disobey absence in order to live in existence”.

This question and questioning expands not only to Black movement(s) in Brazil, but all movements originating from the margins of colonisation worldwide.

Carolina Maria de Jesus’ work is not revolutionary in itself, however, it finds its revolutionary possibility in its importance for post-colonial cosseted facing what she terms, “the second slavery”.

In October, the Moreira Salles Institute, located in São Paulo, Brazil, inaugurated an exhibition called Carolina Maria de Jesus: a Brazil for the Brazilians. It features over 69 artists who present works inspired by or related to the author’s work.

The exhibition also presents Carolina’s pluralities. She works as a composer, a writer of novels, chronicles, short stories and plays.

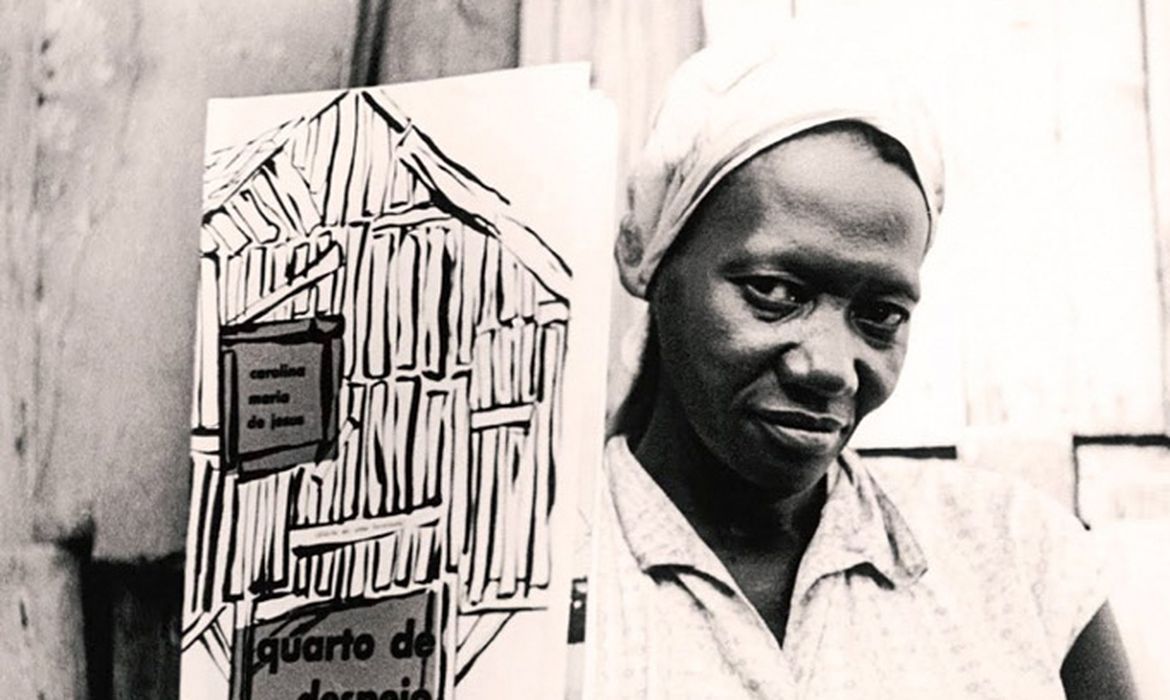

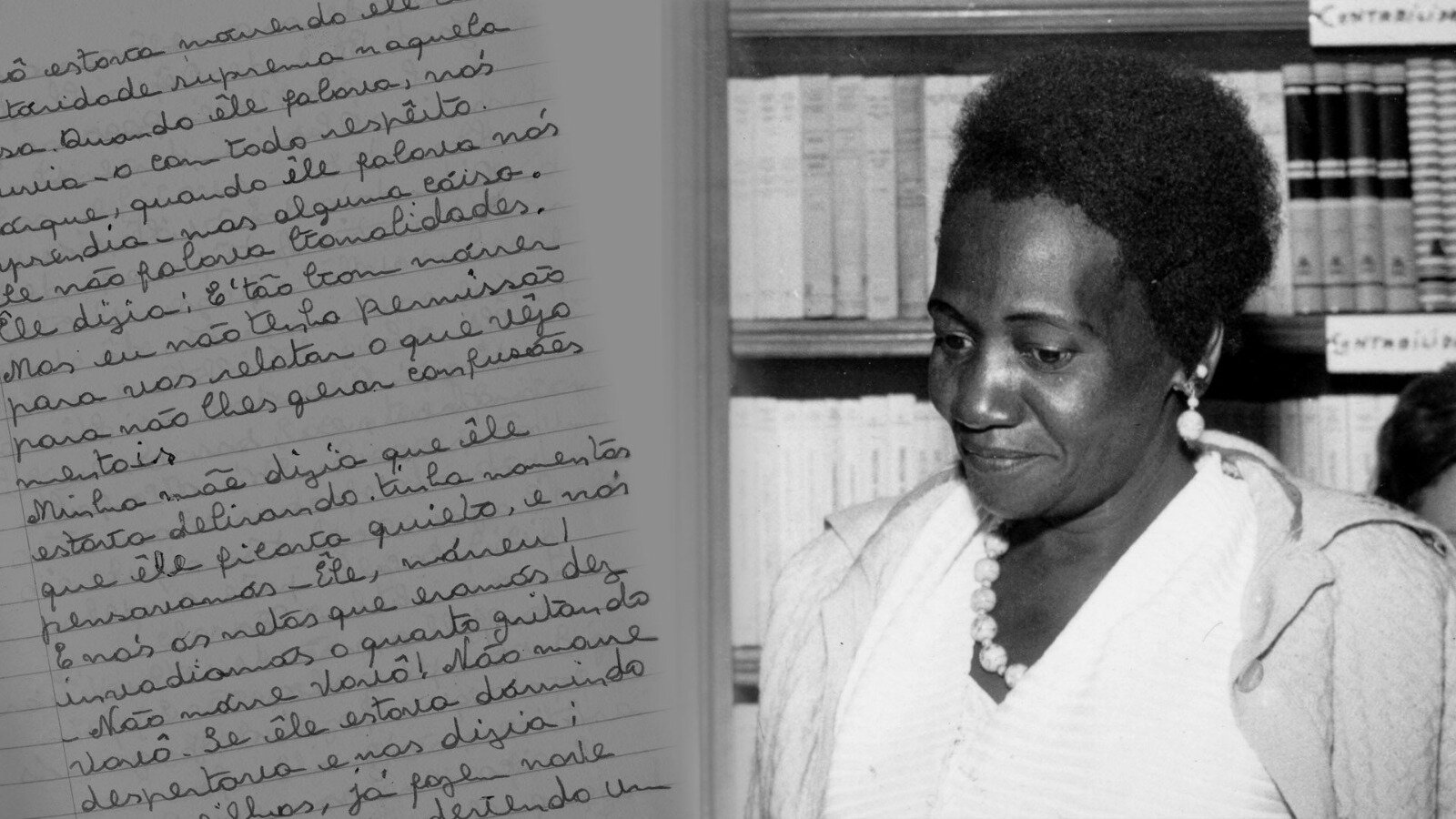

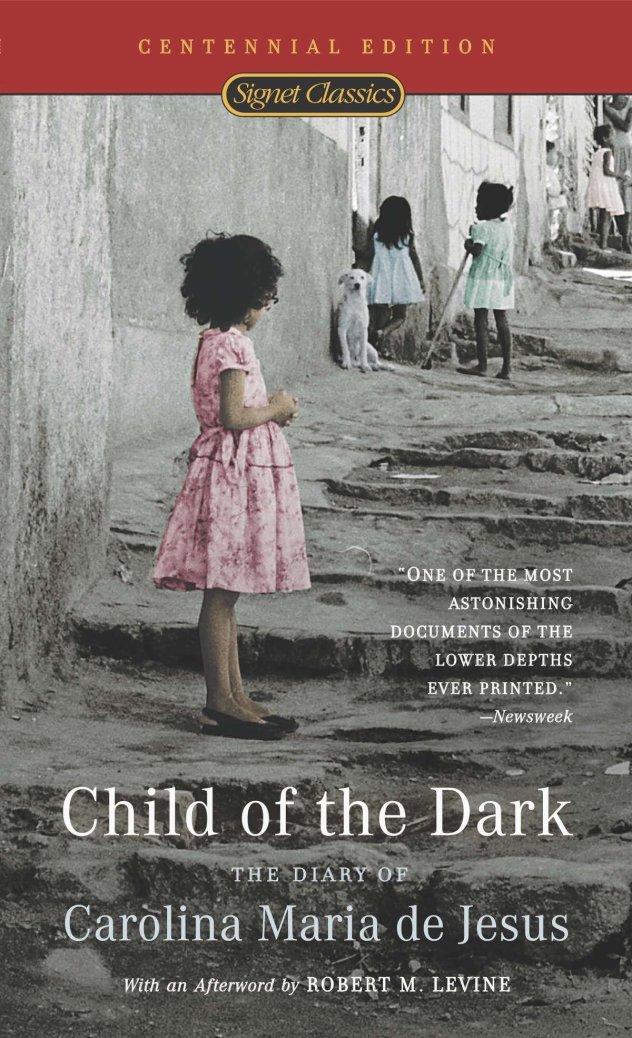

The show also addresses media representations of the author by contrasting images of her circulated in the media: always with scarves in her hair and a sad face.

Contrasted with her personal photographs and those taken in intimate settings: always smiling, with her curly hair showing, wearing pearl necklaces…

The images of Carolina Maria de Jesus shared by the media constructed a “visual discourse” with de Jesus coming to represent a “Black writer who came from the slums and learnt to write by some miracle.”

Another element of Carolina Maria de Jesus: a Brazil for the Brazilians that caught my attention was the curatorial decision to present the exhibition from the author’s own literary lyricism — both figuratively and conceptually.

This connects me in thinking, to the exercise of writing and literature presented by Roland Barthes, positioning writing not only as a literary form but as an art form too.

Carolina Maria de Jesus: a Brazil for the Brazilians presents a Brazil exposed from the point of view of the margin; of the periphery; of Afro-descendent; of specific economic and social positioning.