“I believe in inhabiting contradictions. I believe in making contradictions productive, not in having to choose one side or the other side”.

Angela Davis

I feel the contradictions coursing through my body as I wait on the line for my call to be answered. They spill out all over the place, anxiously announcing themselves through my staccato breath; this is the sound of the internal battle being waged between the things I am unlearning and modern society’s socio-historical scripts. I have known and loved people whose own life story mirrors that of Abdul-Aziz. Family members who I once called malume, however, in his case- death left no room for him to build or envision a redemptive future.

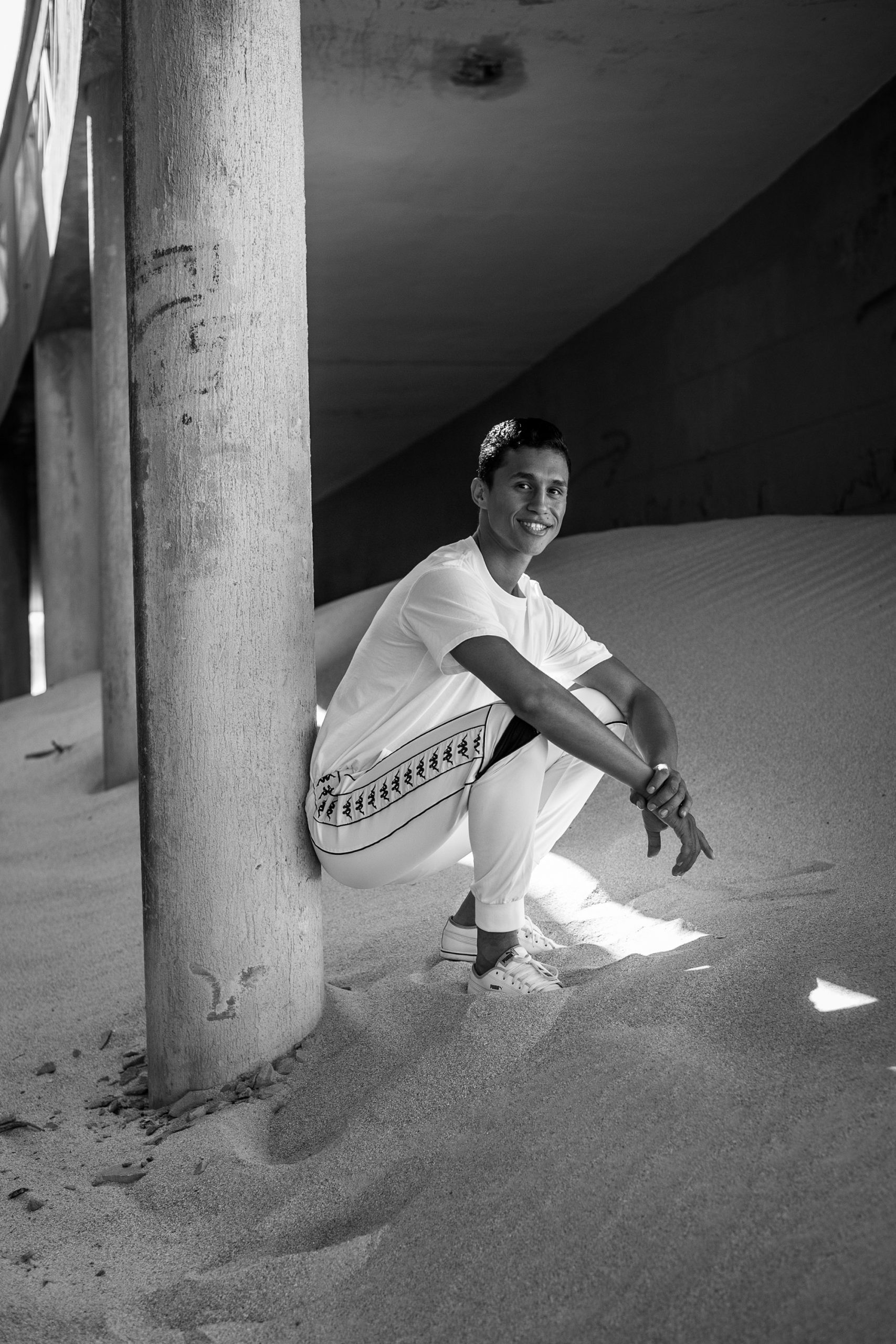

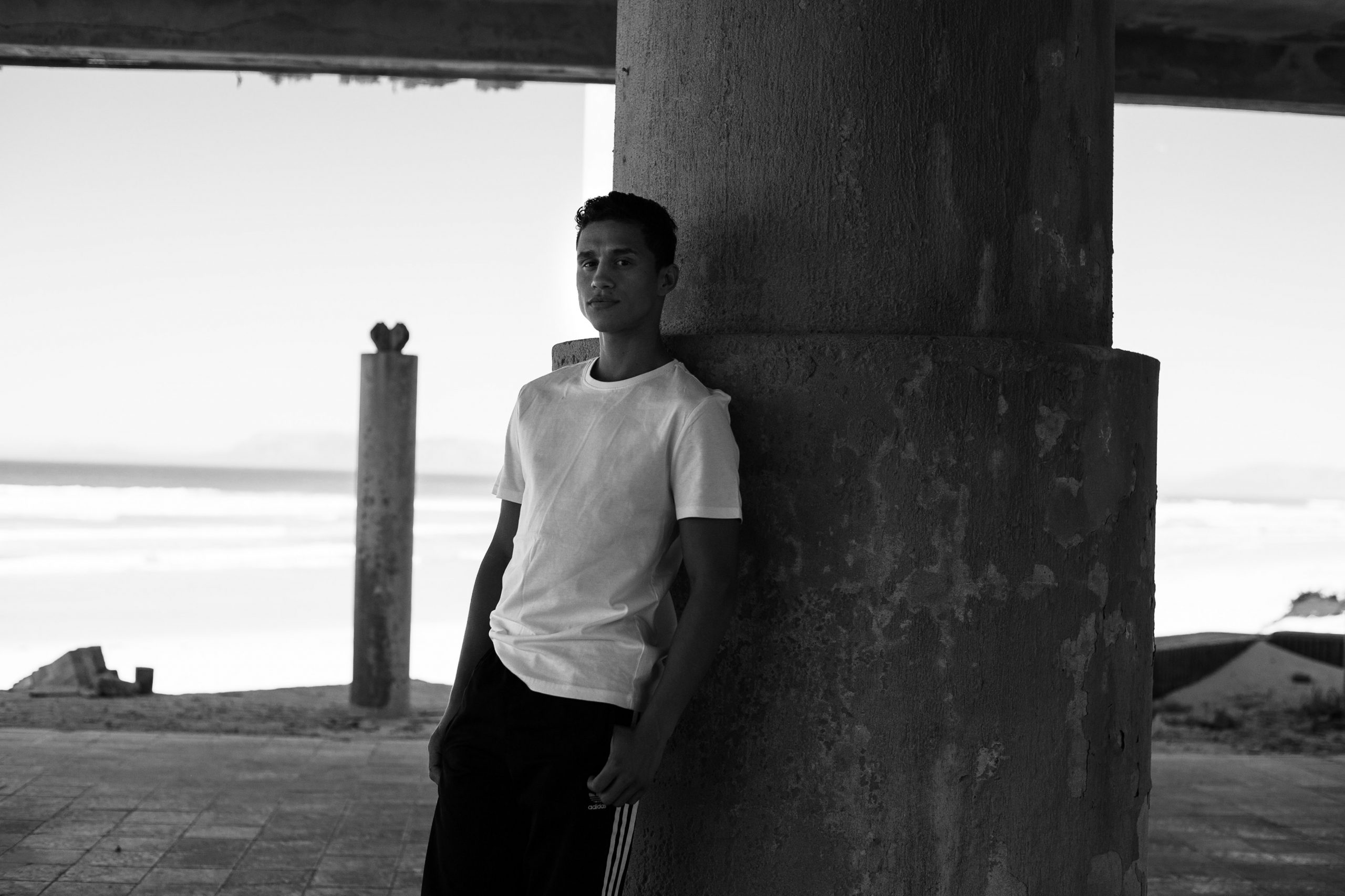

Born in 1994, Abdul-Aziz Kunert grew up in Brooklyn in the Western Cape, “growing up in Brooklyn, it’s a nice place but yet it also has its own dark side”, he expresses while talking about his hometown. Brooklyn, like many other areas falling within the Cape Flats and South Africa’s townships, is plagued by issues of crime, drug use, gangsterism, lack of “integration” into our so called post-apartheid modern society, infrastructure and service delivery. These issues—both causes and symptoms of apartheid’s legacy and its residential spatial segregation—continue to contribute to the unequal distribution of economic access, opportunities and the quality and possibilities of life within our society. Therefore, they also have a direct impact on the country’s high crime levels. Abdul’s story is one such tale that finds its articulation at the intersection of these socio-historical conditions, coupled with choices he made himself—this is not an uncomplicated story. Abdul-Aziz—described as an amazing and independent child who always put his brothers before himself, by his mother—took the number of one of South Africa’s most notorious gangs at the age of 15, after dropping out of school in 2010. In 2012 he committed murder; while out partying with friends, Abdul got into a street-fight and the violent tussle ended up with him stabbing the other individual. After which he was sentenced to 12 years imprisonment at Drakenstein Correctional Facility with a 5 year suspended sentence:

“Growing up with my grandparents always encouraging us to do right from wrong, I then moved to my mother where it wasn’t stable. I didn’t finish school and was a very naughty boy. I thought being on the streets was my only way out because of me having no education and finding love on the streets and in friends. I didn’t think it would turn out to me committing a crime and being sentenced to prison”.

While serving out his sentence Abdul-Aziz was introduced to boxing, which he describes as a life transforming occurrence, “I think I found myself in prison and God has transformed my life through boxing”. As a total rookie trained by former professional boxer Sandile Hoho—who was serving his own jail term at the time and was trainer to the inmates who boxed—Abdul began to flourish in the sport within a month. “He is fast, that guy is a born athlete and you could see during practice sessions as well when he does something, it’s wholehearted. There’s nothing that he does with only half his energy” expresses one of Abdul’s former prison wardens in the award winning short documentary about his story titled Dula. Throughout his time in Drakenstein, up until his release on May 30th 2017, to this very day as he prepares for an upcoming fight, Abdul-Aziz has continued to progress as an athlete and his belief in himself and in his capabilities has never wavered, “I knew I had this in me, I knew it. It actually took prison to show me that I’m actually a good boxer” says the soft spoken athlete. His boxing career, his growth as an athlete and his transformation as an individual are all factors he attributes to his time spent in Drakenstein, and to the power of God—a figure who plays an important part in his life:

“I would say even though I was on the wrong road and that, like my connection with God, I’ve always had that connection. Even though I was in the deepest darkest corner. I think God had set my life out to be as it is today and to transform it through boxing because boxing is a disciplined sport”.

Currently the Western Cape Featherweight Champion, ‘Dula – The Arabian Knight’ is preparing for the WBA Pan African title fight which is to take place on April 18 in Cape Town:

“I’m fighting for a vacant title; a title that none owns yet. This will be my 5th time fighting in the featherweight division. My typical routine training for a fight is running everyday, in the morning early. Then in the afternoon I will go down to the Brice Academy Gym where my trainer is Emil Brice. We train hard. From 3 until 5 we have sparring, I don’t know if you know sparring? A lot of guys will spar against you, depending on how many rounds you are fighting in your [actual] fight”.

His mother, Nazlie Davids has always been his biggest supporter and a source of unconditional love for him. Abdul’s own love for her, for his brother who was killed while Abdul was still serving his sentence and his determination to make them both proud is viscerally felt when he talks about them:

“My mother plays a big role [in my life] since we were young. I think they always say the boys are always closer to the mothers and I always had an open relationship with her. With my mother the love is unconditional, I cannot explain it. She’s always been there for me and I cannot neglect her in anyway. Yes sometimes we have our differences but we still look forward [to the future] together and we will always be as one”.

The criminalisation of coloured and Black individuals from poverty stricken areas heightens the perception that they are threatening therefore foreclosing the possibility in the mind of society at large that they are also survivors of violence; a very particular kind of state sanctioned and socio-political violence. While I in no way seek to disregard Abul-Aziz’s agency in making the choices he did. Nor do I aim to strip him of his power—for as I have said, this is not an uncomplicated story, I do think it is important to be critical of all sides of this coin. While his story lays siege to the history of inequality and its still ebbing legacy, I can’t help but continue to envision a society where everyone’s life is afforded the same opportunities, and where prison is not a rite of passage for some. In a world that has given him little room within which to dream, Abdul-Aziz has the audacity to dream beyond its constraints—a radical act within itself.

“You know, like my dreams and goals they expand every time I achieve them. I hope and I believe that one day I will be a world champion but my focus is to be a national South African champion. I wanna do a lot of people proud out there but especially myself”.