Abstract

The piece that is to follow is a Song of Mo(u)rning from a place of love for my grandmother. However, it is made complicated by its location inside the House of History. With it I fabricate a ceremony of re/membrance and healing.

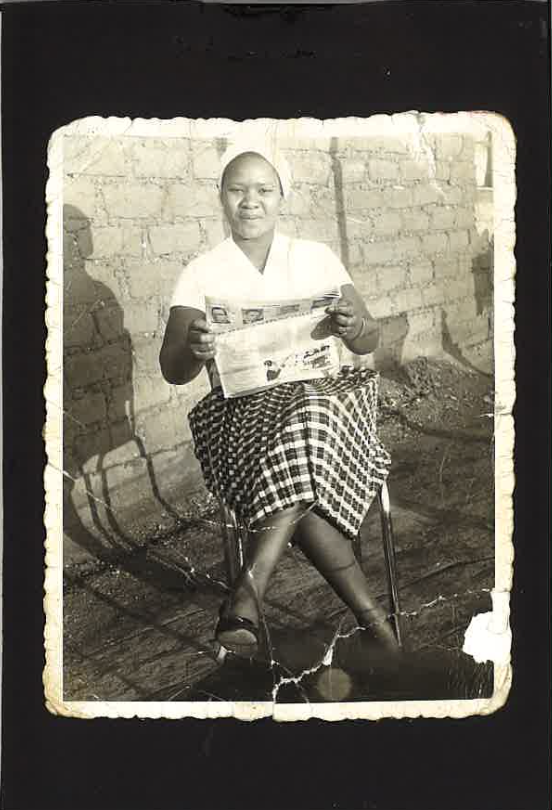

With it I enter into the History House packed to the ceiling with the hissing whispers of those racialized and gendered ghosts, who like my grandmother; Mantsane Alina Qhenase “MaMpho” Mavuso, were a stain on the tapestry of the white imagination and its genealogy of white hetero-patriarchal supremacy and abstracting violence.

In an attempt to break bread with my ancestral trauma and to break the back of History; I write in an intimate language of re/memory and re/covery of her beautiful and ugly. Of her joy and of her hurt, of her wake work.

Lord bless my lineage.

Lord bless the Wretched.

Although, I myself pledge no allegiance to the flag of gender constructs, and consider woman and man to be ties that bind; I want the ancestral hissings of those gendered and racialized dis/remembered to fill the discursive silence. To remind us that not everybody was granted a seat at the table when woman was being defined. For to be considered woman, one first has to be considered full human, thus what does women’s day mean when you move at the margin?

Guided by an Imaginative language of re/covery through re/memory as my companion, I seize my grandmother from the belly of the big white whale and give her a seat at the table she was denied by punctuating the vocabulary of woman with the grammar of a Blackened Consciousness. My grandmother’s wake work, her embodied conflicts, trauma and joy housed so many of the unhomely. The re/memory of her pushes me to be orientated by a questioning of how free and how me I can be in this gendered, sexualized, wholly racialized world.

MaMpho, the world said not you and you cut its tongue out and said always me. Your embodied wake work and radical reclaiming of love imbued me with the formative vocabulary to claim myself as my own best thing. The body remembers, and mine remembers sweetly the tenderness with which you would wake me up for crèche each morning, the soft and wrinkle of the nape of your neck.

The kotas made and devoured in your kitchen after church each Sunday, the spaza you ran from that kitchen and all of the unhomely children and people you housed along the way. Because of you “even as we experienced, recognized, and lived subjection [and abstraction], we did not simply or only live in subjection and as the subjected.” (Sharpe, 2014. 4)

“Wake; the state of wakefulness; consciousness.”

“Wake; grief, celebration, memory, and those among the living who, through ritual, mourn their passing and celebrate their life in particular the watching of relatives and friends beside the body of the dead person from death to burial and the drinking, feasting, and other observances incidental to this.”

Christina Sharpe, 2016

Telling a story is a sacred act of creation. In the stories of people one can find illuminated the accumulated wisdom of hundreds, sometimes thousands of years of shared human experience. Through stories the inherent conflicts and values of the world, its histories and its cultures are revealed.

Stories perform magic tricks that conjure up a transgressive space in which we can confront the constructions that constitute what it means to be defined as human, what it means to be named from within, what it means to be named from without and what place one occupies in the universe and within society.

In the stories of people, those remembered and those forgotten, those who are claimed by the world and those who are rejected by it, the righteous and the wretched of the earth; we can excavate the many buried bodies of humanity and bare their silenced lives witness.

The world will never know the story of my grandmother. A woman of ancient moonlight magic who raised me with her heart and her hands. Hands that knew when to be firm and when to be tender, yet still remained tender in their moments of firmness. Tired Black hands that prayed hard and relentlessly. While raised high to the heavens every Sunday in church, to a God named in a language that cut her tongue to speak.

There is a memory I have of my grandmother’s hand coming into contact with my skin when she would bath me, in a ritual of cleansing she would work tirelessly to wash the dirt away from my body, to wash the Blackness off of my flesh, sinful and cursed in its darkness.

I have often wondered of the trauma my grandmother had experienced in her waking life and through symbolic annihilation. A world that had turned her hands into weapons when confronted with the Blackness of my flesh; an unwavering reflection of her own. Swallowing her up whole as she looked at me.

In the tradition of my grandmother, her grandmother and all unnamed, misnamed (what do you call yourself?) Blackwomen before and after her, I inherited and swallowed her trauma. Sang it as my own that staccato song of her fleshly unmaking, made a sacrificial alter of my bathtub which held holy waters in which I’d pray for a beauty that was divine. A beauty that looked nothing like mine.

I had inherited her loss, ignorant of the improperly buried ghosts that made up parts of my melody’s orchestral choir. With time, I came to know that they were full of sadness and pain these ghosts of ours, full of hues of blues that spread out into oceans of forever loss.

It is difficult not to come to a knowing so deep of those etched onto the surface of my skin, deeply rooted in certain dark things beneath my flesh. Those whose scents move freely between my shadows and soul.

I grew up with my maternal grandparents in the dusty township of Sebokeng Zone 7. This was until I started living with my parents at the age of 6 who were still strangers to me then in many ways. So much of my childhood nectar was and remains my grandmother. She was the most beautiful summer I have ever known.

I often wonder of the many ways in which she was robbed of being able to give language to her hurt, to name her ghosts. How there was never time for her to sit down with them, and contemplate them completely in moments that stretched outside of time.

I mourn how she was denied a space that bent time and resisted all the names the world had given her, where she could breathe softness and love into the wounds of History. I mourn too for the impossibility of a Clearing that was all hers where she could perform intimate ceremonies of self-recovery and teach herself and claim her body as her own best thing.

I think that there is a secret we inhale while nestled in-between matswele anNkgono, and carried in the deep recess of our souls. A secret of a portal where the skies meet the waters. My grandmother’s smelt like ancestral trauma and complicated love. Death and resurrection. I often ask myself where the unhomely go to rest their heads. Where are their dreams housed?

Mine found a place to belong in the love work performed by my grandmother, as shrouded in complicated History and interwoven with ugly feeling as it was. Me, and mine found home in the joy she sang into her kitchen while making me sour porridge on Saturday mornings. She showed me fiercely, how I was indeed my own best thing to be snatched back in the dazzling of the sun from the darkness of deficient the world had tried to hide me in.

Every night as a child I would lay down beside my grandmother in bed and listen to her fight in her sleep. I wish now that she would have let me into her dreams, invited me to the places she wandered off to. So we could talk about the ways she had to eat herself up to survive in her waking life. The ways she had to set herself on fire. Make herself small. Of the languages she had to forget and the ways in which the world made her disremember her body and forget its human glory.

I wish she would have told me of the ways this world had tried to make her forget her true. If this had happened, perhaps there would not be so many of those ghosts lingering behind on the face of my mother and then on mine.