“Once you overcome the one-inch tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films.”

– Bong Joon-ho in his Golden Globes acceptance speech, 2020.

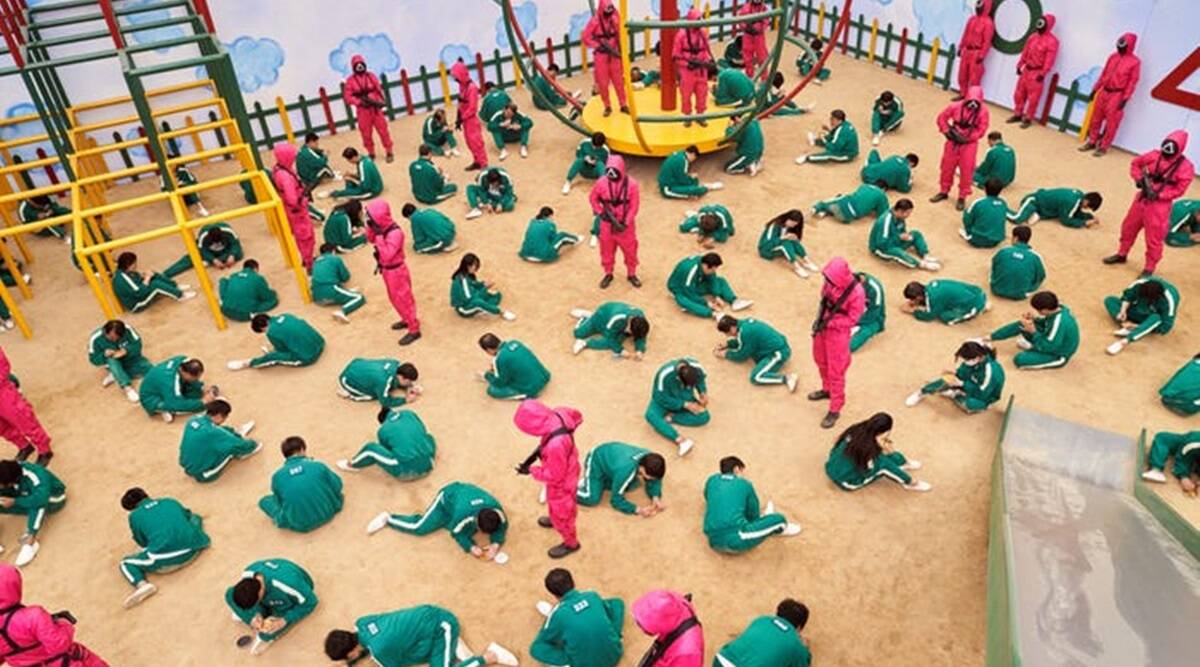

[SPOILER ALERT]

You have probably seen this quote being passed around on the timeline since the release of Netflix’s Squid Game – with reason.

Just as in the case of Bong Joon-ho’s award winning Parasite that set the world ablaze with hot takes of capitalism and its effects on the working class; Squid Game has reignited the since diminished flame on the dynamics of capitalism and the kind of action it incites in working class citizens – actions based on the need to survive.

While there has been no shortage of cinema and art covering capitalism – its benefits and shortcomings – most of the entertainment that we have access to and display a willingness to engage with has been from a decidedly Western perspective.

From Mr Robot to American Psycho to the Wolf of Wall Street, South Africa is inundated with access to information covering this topic from a particularly North American lens; a lens that typically explores the collapse of this system and the breaking of the people at its helm.

In the aforementioned series and films, we look at the breakdown of the aggressively capitalist characters and the people that benefit from this system. This, of course, is an oversimplification of a – still – valid perspective.

However, part of the beauty of Squid Game is the portrayal of the grim reality of working class livelihoods and its entrapment under the control of successful capitalists and the system as a whole.

Squid Game is not even a critique of the system per se, just a demonstration of its destructive power and a colourful portrayal of the brutal climb to the top.

What Squid Game shows us is the truth – the system does not collapse, it persists. In Hwang Dong-hyuk’s Squid Game, we zoom in on the working class’ dependence on the same kind of violence that subjugates them.

In the first game – Red Light, Green Light – the best strategy for the success of the game is to hide behind someone else to allow them to take the fall and to decrease your chances of getting spotted and shot. This need for other people to fall to secure your own survival and build towards winning the entire game is hammered on consistently throughout the drama.

In Tug of War, where the one team must be defeated to their death, the inverse of this is that more lives lost leads to a significant increase in the prize money. In this way, Squid Game dives into how capitalism’s viciousness manifests in those who are struggling and desperate.

The characters are backed into making difficult choices, unlike the game masters who chose to build a sophisticated game system on an island with an obscene amount of money offered up as prize money – as opposed to simply settling the debts of the characters that most needed to be helped.

And sure, some characters fully embody this expectation of brutality and callousness but in a game that awards money for lives lost and kills off characters that display kindness, what chances are given to any characters to make good and humane choices?

The way game masters actively rewarded bad behaviour directly mirrors reality, where wealth is often built on the suffering of other members of society.

This is only one aspect of the discussion of the magic that is Squid Game and it serves as a sterling example of the kinds of interesting and educational perspectives on topics beyond capitalism that can be found beyond the barrier of subtitles.