Since December — after my brother and I attempted to attend an event thrown by a youth culture/street culture group in collaboration with a youth centred media organisation — I have been replaying and rehashing a certain situation in my mind.

The youth/street cultural group claims to represent the youth/streets — it’s run by the youth and aimed at building on local street culture by promoting their community’s culture to the world. The group’s ethos is centred around opening up the creative industries for people like them, to build a legacy of voices from the street collected together to create something that they and the world can admire.

This was a vision my brother and I respected and wanted to be a part of in any small way. “Yes! Create spaces where the voices and conversations of talented creatives and youths from the street can intersect and create something special”, was our proverbial exclamation. So of course, when the cultural group had advertised an event for the youth/streets on their IG, we had to attend.

All were welcome to this event — which is to be expected, I mean it’s by the youth for the youth, of streets for the streets. Exclusivity just wouldn’t be the natural choice here. Sure the location was a bit out of the way but that is the only cost for prospective guests to incur. It appeared to still be doable.

We get to the event gates on time but African timing is incredible so we are hilariously early and the event contractors are still setting up. In any case, we try to get in and wait it out on the inside, which is where we are met with a dark entryway reminiscent of some of the clubs and exclusive space I have visited in Sandton, Menlyn, Osu and East Legon.

We were greeted by four or five sulky faces dressed in all black, with slick hair styles and beat faces, which looked good… but I was a bit taken aback. This event was supposed to be open to all, so why the guards and gate checkers? “Maybe this was about building a VIP atmosphere for the youth of the streets to experience? Yeah, maybe it’s something like that”, I ask and convince myself. Upon learning the ticket price, we realised instantly that that was not the case.

“The ticket is [$61]”

This may not seem like much to some. In fact, I even attempted to just buy the tickets, enter the event and focus on a good time — but thankfully, my brother who is more principled than I — stopped me and asked to go back home.

There were two problems with the price, firstly, it wasn’t advertised on the poster and there were many young people that showed up around the same time as we did and were chased away by the cost of the ticket. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, that was quite a steep entry price especially for an event geared at the youth of the streets, run by a group that supposedly represented their interests in the creative community. The price coupled with the exclusive, snooty faces with ipads at the gate made it immensely clear, this wasn’t a space for them.

Mulling the event over in mind these past two months since it occured and after conversations with people who knew about the event, who attended the event and who tried to attend to the event, I can finally place my finger on what felt so icky about the event — it was the use of the aesthetics of struggle to promote and empower capitalistic desires. A mechanic that is as ubiquitous in youth cultural organisations as it is insidious.

Youth groups in fashion, music, media or some other creative industries dress up messages of violent aspirations for obscene amounts of wealth at the expense of ethical practice in loose threads that present their interests as noble and ultimately for the streets, the youths, the hoods, kasis, threnches and whatever else slang they can co opt to build an air of authenticity.

They develop merchandise and products based on symbols and sensory languages of the youths, communities and sub-cultures they claim to represent. They speak out non distinctly about how all the “cool shit” they are doing is ultimately for the streets, a gift to the people.

They praise themselves through the voices of others, say how a kid or something ran to the arms of the founder and express some joy about how they are putting their communities on the map, being an example that they too can follow to amass the same amount of wealth, respect and power.

But no, they aren’t really putting their communities on the map, they are leveraging the aesthetics of that community’s struggles as texture that boosts the perceived authenticity of the “cool shit” they are doing to gain buy in from people completed disconnected to the realities of the cultures and communities that have been repackaged from their consumption.

That isn’t a streets to the world story, that is just the economics of clout.

Moreso now, and for whatever reason, the world seems really interested in trickle up trends – where cultural trends start with lower income/status and youth classes and move up into higher income/status classes purview.

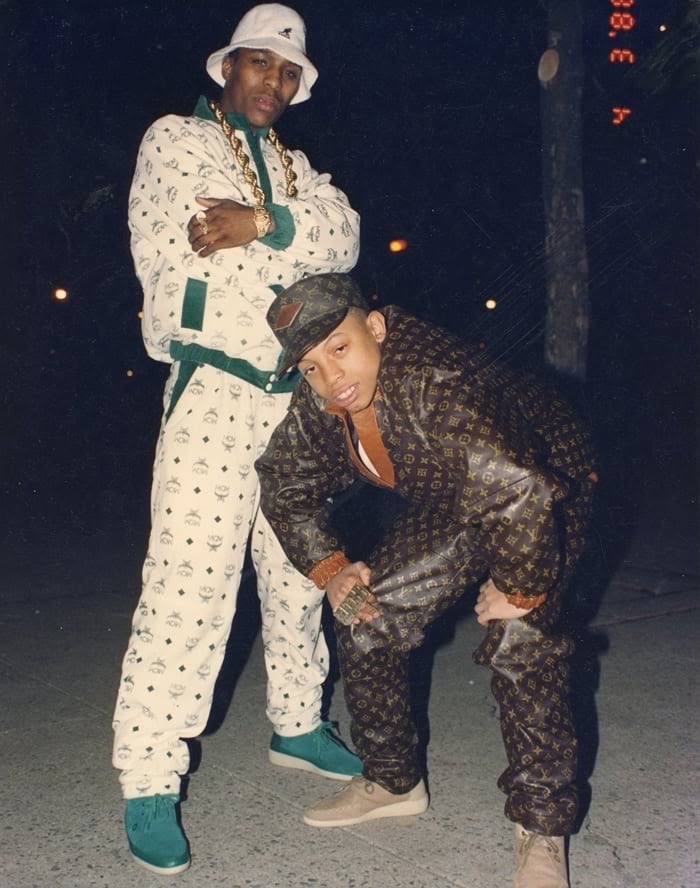

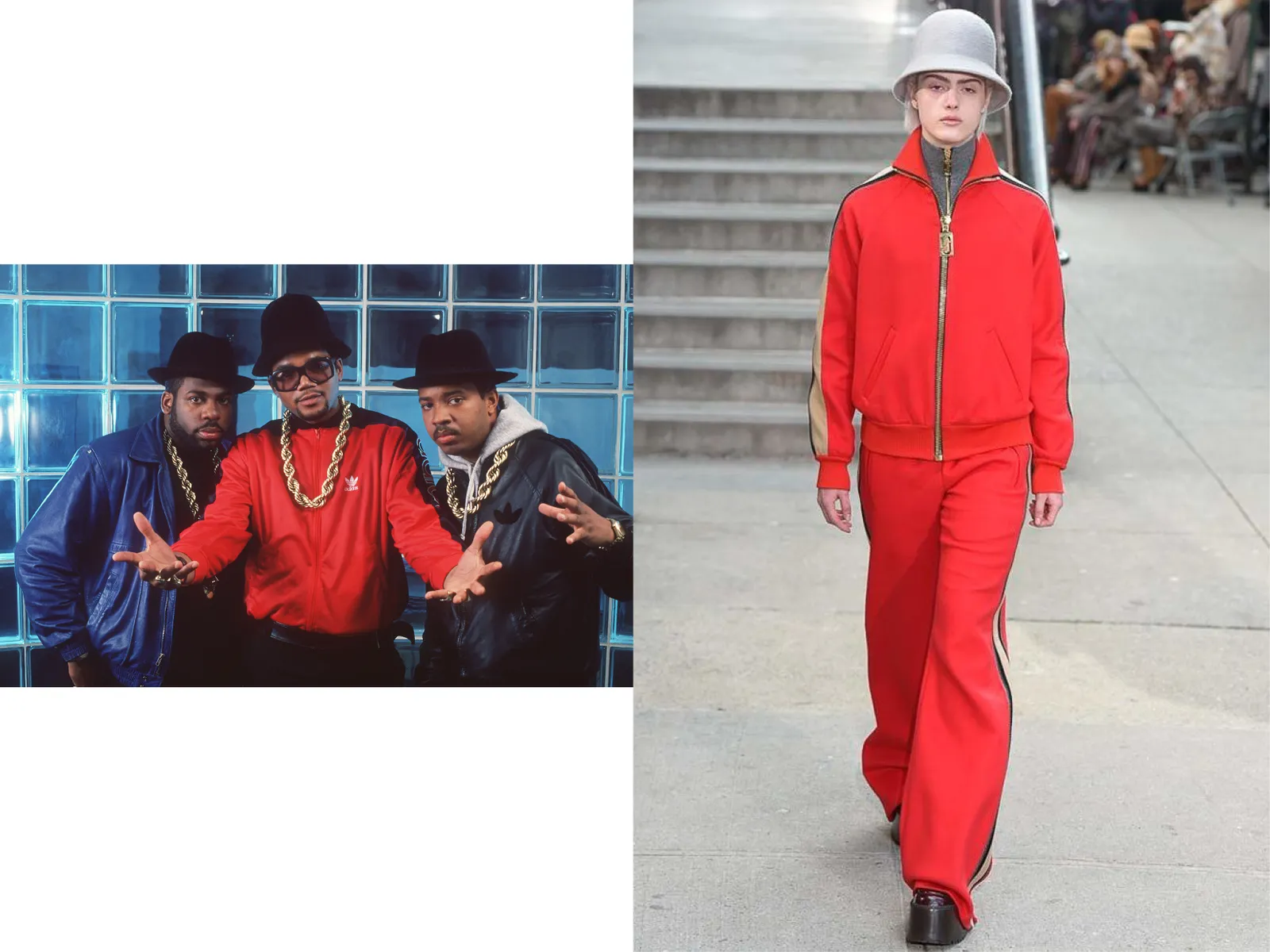

In fashion, we have seen this manifest in a number of notable ways over the last few decades. One of which is the streetwear trend where clothes and their styling had been taken from African American communities and sub cultures like hip-hop, and repackaged as high fashion on the catwalks of brands like Prada, Gucci and Louis Vuitton, to name a few — only to be sold at prices that shut out the originators of the trends.

This seems harmless enough but the idealisation of aesthetics more commonly associated with struggle, imputed into the clout machine, then performed by people completely detached from the culture — who subsequently shut out the community and cultures where the style or aesthetic was extracted from and then economically benefit of a newly packaged “trend” — is what seems particularly malicious to me.

I think that is what I found so heartbreaking out of this whole ordeal and other manifestations — it was that it did start from the streets – they are youths from the street. So why take your own culture, reduce it into an aesthetic, and use that to promote your own growth that shuts out the very people you started with, the very community whose culture you used for your success. Transforming your organisation to a clout-based machine you use for entry into exclusive spaces that value “authenticity” and the opportunities they can purport through it, shutting out people like you.

It was just $61 but it said more about what the group was truly focused on than I was prepared to accept. At that point I already bought and owned a t-shirt by them that must have cost over $100 but it just hadn’t clicked then that a uniform for the youths and street shouldn’t be that out of their price range. I thought, clothes can be expensive to make and distribute and portions of the proceeds could be redirected into some other spaces for the youth/streets to access.

However, the creation of a space so limited and exclusive which could have been easily opened to the streets, yeah, that’s harder to make excuses for. Maybe this was a one-time affair and I still hold a hope that there is more beyond this event that I have no access to understand – more than just a leveraging of the aesthetics of struggle for the economic use of clout.

Alas, this hope may forever hang in time as just that – hope, unfulfilled hope.