The 90s saw the advent of streetwear rising to the attention of the elusive “fashion” crowds around the planet. A blend of minimalism fused with grunge marked the decade – with Marc Jacobs being fired from Ellis Perry for sending models down the runway in plaid prints and Dr Martens. Shawn Stüssy’s scripted logo, originally intended as a rebellious anecdote for the surfing community, became the namesake of the hip-hop and streetwear scenes; and the script had already been written from the 80s. The script of streetwear is still being written as the nexus upon which “style” or “trends” are both totally informed and simultaneously disregarded by. The unfolding of streetwear marks the notion of people from the ground up creating the story of fashion; as opposed to analyst paid by conglomerates to tell us what is “cool”.

In a world that is currently facing pandemic as we rush to unify ourselves against a virus; systemic challenges present themselves in glaring daylight. We have been harshly reminded of how we all exist within survival mode; perhaps even informing part of our creativity, yet it has been compounded into a structure of economic, political and other such ideologies that draw us away from the innate connection we have to the greater planetary system and each other. It is within this context of collective awareness that the story of streetwear has some obstacles to overcome; namely over-production, diabolical manufacturing ethics, textile waste and an overall contribution to the larger and deeply flawed fashion system. It is my innate feeling that no one in “fashion” is exempt from looking at the fundamental dysfunction we have inherited and perpetuated, even in the pursuit of informed, intelligent and creative design.

With that said, there are brands doing incredible work to combat this narrative; and this interview intends to communicate the brilliance of the collaboration through local designer Daniel Sher of Good Good Good and textile designer Benjamin Nivison. This union was seeded some time ago, and its entry into the local market is somewhat reminiscent of a parallel universe in which Wu Tang Clan adopted the Vedas instead of Shaolin philosophy – a unique cross-cultural collaboration coupled with sustainable thoughtfulness, that urges serious consideration of holding ones vision with intention; until fruition.

Q: Incorporating textiles from traditional weaving methods into a streetwear/contemporary collection feels both bold and unusual; what instigated the conceptualisation of this move for Good Good Good?

Daniel: We’ve (Good Good Good) been working towards a more conscious approach to sourcing our raw materials for the past 18 months. Benji introduced himself to me at a collaborative event that we were throwing collaboratively with Hokey Poke for their first birthday way back in February 2018. That night, we had a long and inspiring conversation and on the evening, it wasn’t even necessary for me to see any of the pictures of Benji’s work to understand that he was in the process of making an exceptional product. In our excessively digitalised world, his passion for traditional textile manufacturing processes was the breathe of fresh air that I needed to positively change the sourcing philosophy at Good Good Good.

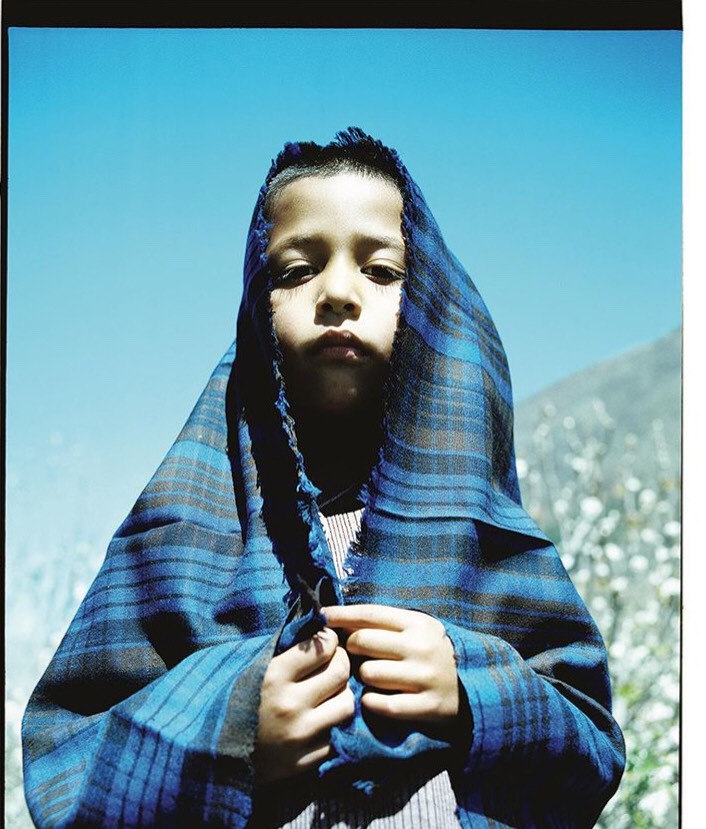

When Benji eventually returned from his journey to India and visited me with his beautiful merino wool textiles milled at Bhuttico, I instantly knew I would be working with him on a future collection.

Q: Personally, collaboration seems like the antidote to the individual-centric nature of most business models; what was the biggest challenge in bringing this collection together from two different perspectives while maintaining a shared vision?

Daniel: At the first meeting after his return from India, we sat in our CMT factory in Maitland, and we were both transparent and open about our individual goals for our businesses. It was clear that we were both thinking similarly about global success, and so our dreams were aligned.

I would say that the main challenge was about how to use the Nivisson textiles and when was the right moment to use them. Having invested a huge amount of time and energy into the textile collection, Benji was eager to get going, especially since he has given Good Good Good exclusivity to the complete capsule of the Woolmark Approved Nivisson Tartan. However Good Good Good was in a position of rigorous flux and realignment, and we couldn’t activate with the Nivisson tartan for some time. We in fact only used the textile for the first time in July 2019, and have been working together ever since.

We now intend to enter our collaboration into the official Woolmark Prize for 2021.

Q: Can you elaborate on The Bhutti Weavers Cooperative Society involvement with the collection, and was it an educational experience in terms of your knowledge on milling and fabric production?

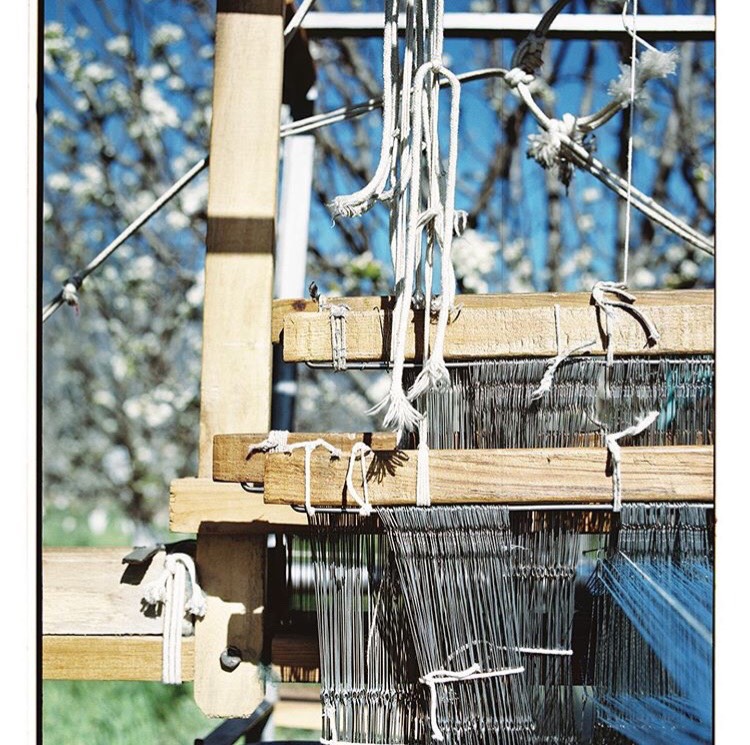

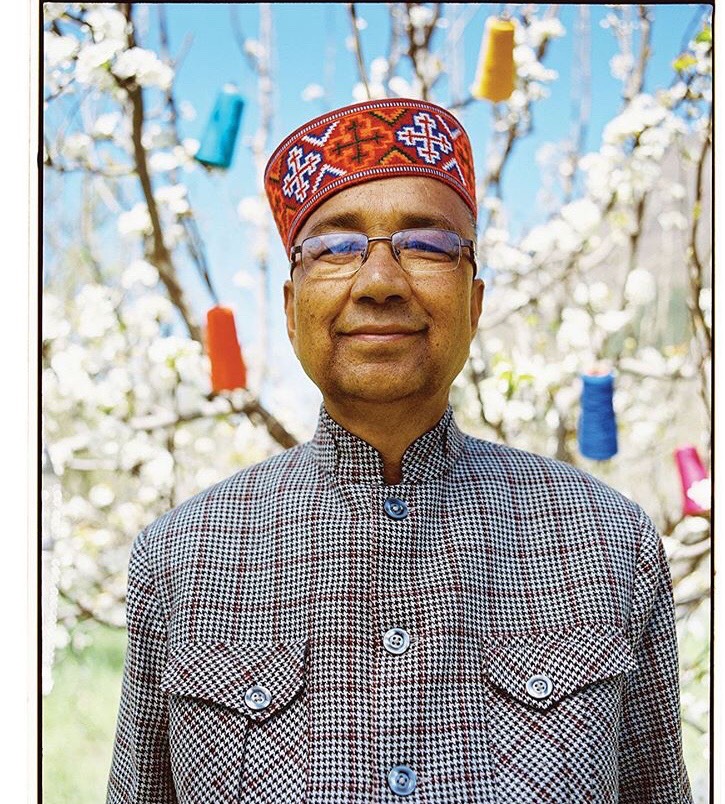

Benji: Bhuttico’s enthusiasm and willingness behind the project was incredibly helpful. They opened their doors to us and all that we needed. Our time constraints were very tight and it took a lot of sampling and tweaking before we arrived at the desired hand and weight of the final collection. Only their master weavers were used in the production and the complexity of the tartans to produce by hand is an incredible feat of concentration and accuracy. In terms of education, I was very familiar with the machines and modes of production. What was incredibly educational and inspiring was the organisational elements behind the society. The love and commitment that the entire community felt towards the society was truly beautiful to witness.

Q: How would you like to see Good Good Good continue to grow as a platform for both clothing and streetwear culture, yet with a firm stance on sustainability? Is there a place for sustainable streetwear in the market?

Daniel: We like to view our brand as one part of a larger South African (and global) community project. Everyone we work with is either already a friend, or someone who becomes a friend. Our stance on sustaining the lives of South Africans working in the fashion industry has been front and centre of our core agenda for the last 18 months. We only work with South African mills where possible, and 85% of our raw materials are now manufactured in South Africa.

We have received a very positive response both from consumers and the media (both locally and internationally) since we consciously turned our attention towards thoughtful sourcing. I feel that although hype is still currently way more important than ethics in the street wear consumer market, the consumers are beginning to wake up our planet’s vulnerability, and any efforts that small brands are making to be kinder to it should be acknowledged. I suppose this is where the art of communicating an honest and transparent story to the consumer becomes even more important for brand owners today.

I think that in South Africa there is a growing market of observers who appreciate ours (and other local brands’) sustainable fashion efforts, however, internationally there is an existing market of consumers who are already educated and can afford to pay for sustainable fashion.

Q: Sustainability” is often marked by the notion of localised production – do you feel that is not necessarily inclusive of the myriad of artisans, skillsets etc. that can be employed across the world?

Benji:

Sustainability has many faces. Preservation of culture, ethical sourcing and local production are just some of those faces.

Daniel:

Absolutely. Some of Mungo’s (a long time textile collaborator of Good Good Good) finest rayons come from Italy, and are then combined with South African cottons to produce their world class South African-milled chenilles. We salute the Italian rayon farmers, pulp producers and yarn spinners involved in this very special product. Similarly for Benji’s Indian produced merino Wool. The wool sourced in Australia, we salute the ethical Australian sheep shearers, spinners, the Bhuticco weaving society in the Himalayas and finally Benjamin, the Cape Town textile designer who mastered his craft at a university in Tel-Aviv.