In the 1920s, Josephine Baker left Jim Crow America for Europe. She had spent her youth between the streets and stages of St Louis, with no stable place to live while performing as a backup dancer for show troupes. Dreaming of stardom and tired of being too black to enter her own shows through the front door, Baker sought out a new life and career elsewhere. It was in the sexual chaos of Berlin that Baker found her place as ‘The Girl in the Banana Skirt’, performing her dance routines across the city for legions of fans. She prepped herself to return to America one day and cement herself in her home country.

When the Nazi’s chased every non-Aryan from the city, 19-year-old Baker left again for Paris: the city that would make space for her to become the world’s first black superstar. At one point the highest paid woman on the planet, her picture on the pages of French Vogue were something no black girl from Missouri could have dreamt up in 1925. From St. Louis to the world, it was Paris to whom Baker dedicated her life. Paris, Paris, Paris. “C’est sur la terre un coin de paradis/ Paris, Paris, Paris. It’s the land on the corner of paradise” she sang in “Paris, Paris”. It’s her song, and its energy that dreams of Paris as the place to be, that Djibril Diop Mambety weaves throughout scenes in Touki Bouki.

Forty-seven years after Baker first arrived in Paris, Dakar was in the thick of post-independence fatigue. The 70s marked a time in which the international oil crisis was dragging an already vulnerable Africa into what would become a long and desperate economic recession egged on by the World Bank and IMF’s neo-colonial economic policies. The decade previous saw a liberated Senegal leading the continent as one of the most politically stable and culturally important countries to gain independence. Leopold Senghor (who would go on to become president for a 20-year term following independence) and his Negritude movement had captivated the attention of the French world, both black and white, with its message of black consciousness and pan-African solidarity. By 1973 this was no more. The slowness of ‘Africanization’ saw a new brand of pessimism and distaste for the government and the country itself grow amongst its people. This is the 1973 inside which Mambety places Touki Bouki, and its enigmatic central couple.

Set against the backdrop of a bustling and dazzling Dakar is Anta and Mory: a young couple who dream of going to Josephine Baker’s Paris. Anta, a student, and Mory, a cattle herder, are both tired of hard work and poverty and believe something better awaits them across the Mediterranean. After agreeing to leave Dakar together, the two engage in an elaborate set of schemes (ranging from petty theft to borderline solicitation) to pay for their place on the ship sailing to France. After packing up what little belongings they have, Anta and Mory wait on the gangplank to board the ship to their new life. At the moment when it is their turn to board, Mory is overwhelmed and turns to run off the plank and back into Dakar, leaving Anta to travel to Paris on her own.

Mambety’s story of disillusionment with home and fantasy of elsewhere has become a cult classic since its premiere in 1973: both for its futuristic cinematography and its critique of post-independence. It’s been hailed as one of Africa’s seminal films. Martin Scorcese recently chose to restore the piece for his World Cinema project. Beyoncé and Jay-Z referenced the movie poster for their On the Run Tour press images. At the heart of this cult film is the idea of chasing your dreams: even when you’re not sure where they lead you. The notion that one can fantasize about a life outside of the present and construct the present around the idea of something they’ve never tasted is at the centre of Mambety’s project.

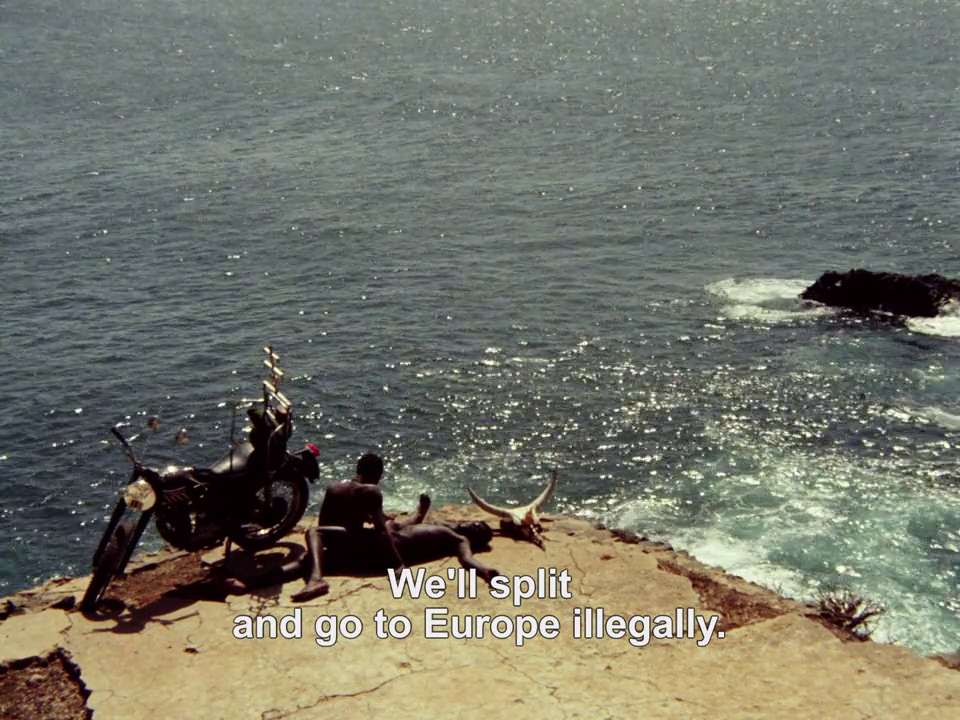

Paris has long been the site of dreams for young Africans. The Negritude movements celebration of art, old ideas of France as the land of intellectualism and tough economic times stewed together to make Paris the place to be. This is the reality Senegalese youth lived in and in which Anta finds Mory by the water early in the film. After they make love on the rock, the two lay in the sun together and dream of Paris. Mory tells Anta that they should catch the ship leaving tomorrow and she jokes that he can’t go anywhere before he pays the debt he owes for rice. With all the braggadocio in the world he replies “All we need is a bit of ready cash. Hang around the right guys. Tip the right people. France, here we come!”. The idea that Paris is better, simpler and without the hang-ups of where they are now is borne of the afro-pessimism that characterized the decade. When Mory and Anta lie on the rock, they dream not just of leaving but of being completely free of where they are now. Mambety’s characters have decided that, for the time being at least, there is nothing left for them here because everything worth having is on the other side.

The dream of escape is entangled deeply with the dream of home. For both Anta and Mory, their desire to leave is enmeshed with a desire to return as people wholly different from their present selves. Mambety shows the characters desiring this grandiose level of self-importance after they rob Charles (a wealthy homosexual who propositions Mory for sex at the waterfront). After fleeing the man’s house, the couple enter a dream sequence where they get into their car and drive across the city past the Presidential Palace. Donning the clothing they’ve stolen from the man, the two greet adoring passers-by as though they are the President and First Lady.

Their dream of returning from Paris as people of stature is the culmination of their desire to come back someday. As Fanon said, “the black who knows France is a demigod” in his own country. Paris is the place oversubscribed for the success of the African. In many ways, the couple views France as the key to success for betterment at home. This future vision of themselves as people who matter in society is a far cry from their current roles as the Bonnie and Clyde of Dakar.

The stakes for Anta and Mory seem unmistakably high in 1973. They are the product of a liberation failed and a future that comes with a price tag subject to fickle inflation rates. In many ways, Anta and Mory are in the same dreamboat to Paris as the thousands of economic refugees fleeing West and Central Africa today. When a place seems to offer you nothing but unkept promises, it only fair to seek success elsewhere.

Despite what xenophobes and the alt-right will tell you about migration, the process is not simple. Most stay, and those who leave don’t always find it easy to do so. In the final scene, Anta and Mory stand together on the gangplank to board the dreamboat to Paris: bags packed and futures awaiting. When it is their time to step on the boat, only Anta goes. Mory turns and runs at full speed back into the city in search of his old motorbike. The scene flashes between Mory running and a cow struggling at the slaughterhouse, both fighting furiously for breath and relief from the darkness that the future holds. Anta, for her part, sits in her stolen suit alone on the deck of the ship as it moves away from the port. By the time the credits roll around, Mambety leaves both characters looking deeply unhappy with their separate choices. Migration and the binary between staying and going is complicated.

By the time 1973 rolled around, Josephine Baker’s star had fallen, and she was two years away from her death. Outside of the Harlem Renaissance, she’d failed to become a major star in her home country. She was living out her final years in an adopted land as the mother to a group of multi-racial adopted kids she was calling “The Rainbow Tribe”: an attempt to prove to herself that race was no boundary in her life. Her own dreams of stardom in Paris had been complicated by life, love and the feelings of rejection from home. Bakers life had been an achievement of part of her own dream and the disillusionment with other parts of it. Paris, the land on the corner of paradise, had offered to her both success and disappointment: a dream split between herself, home and this new place. For Anta and Mory: Paris seems to offer a similar future, and Mambety knows this. The pull to find the life you dream of elsewhere is always complicated by the dreams of what home could be and the reality of who you are and what little bit the real world will allow you to have.

If you have the data, you can stream Touki Bouki here.