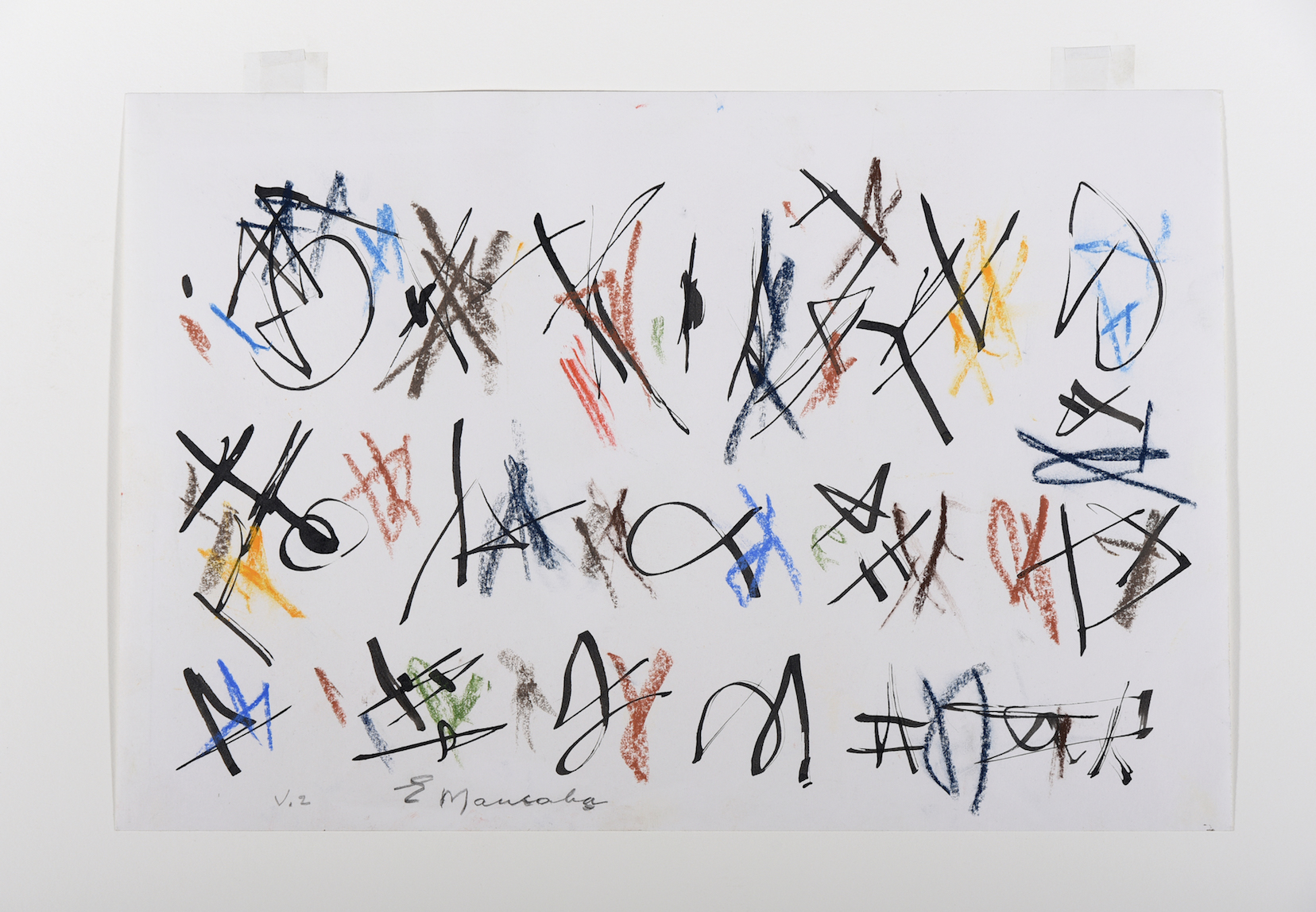

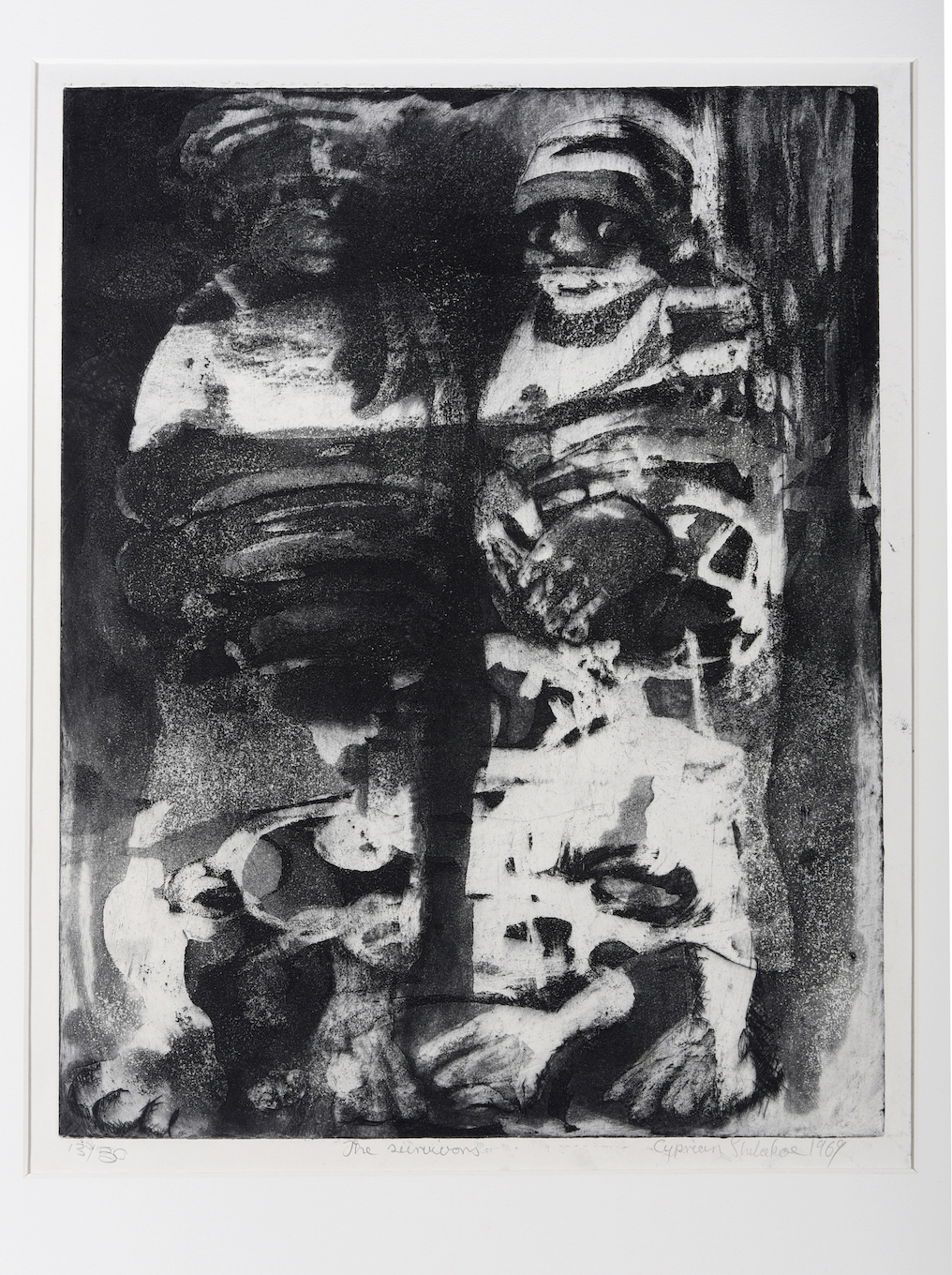

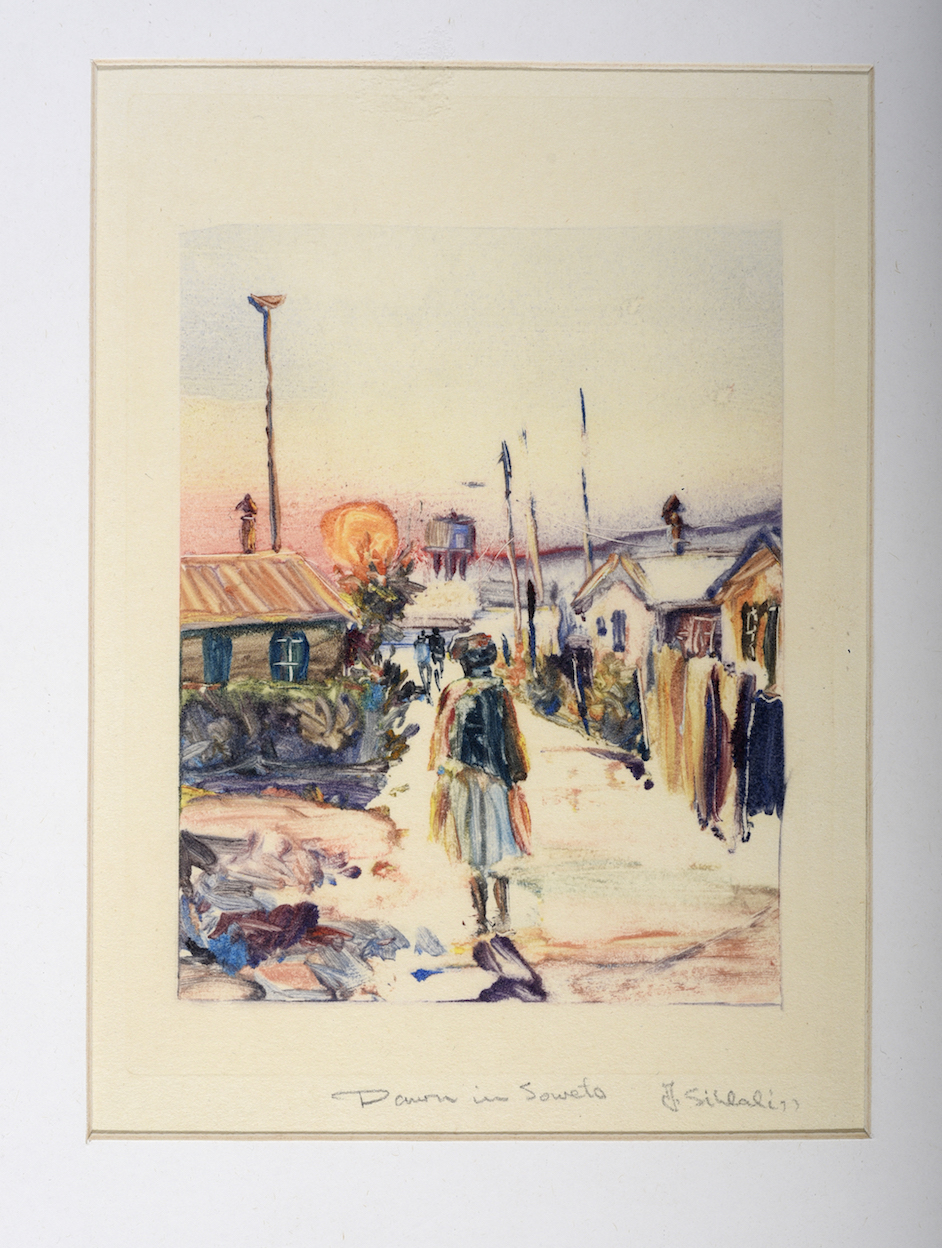

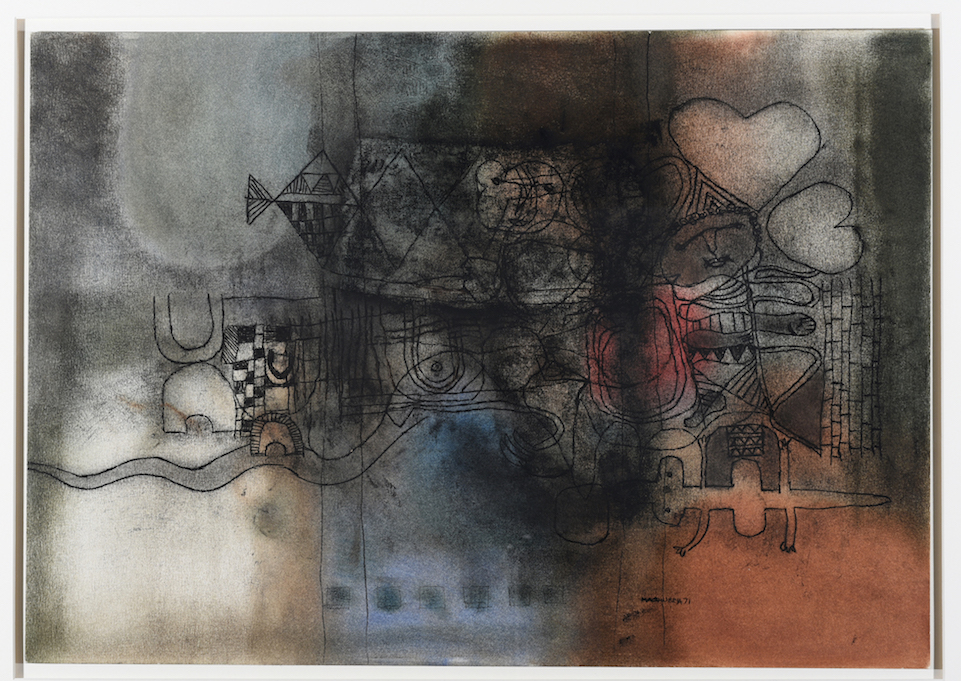

A Black Aesthetic: A view of South African Artists (1970 -1990) presented by Standard Bank Gallery, Johannesburg revisits the art collection of the University of Fort Hare. Exhibited for the first time since 1992 outside of the Eastern Cape, the collection holds one of the country’s most expansive assemblages of Black South African artists working between 1970 and 1990. The Fort Hare art collection was declared a National Cultural Treasure in 1998 and includes over 150 artists such as Dumile Feni, Gerard Sekoto, Gladys Mgudlandlu and George Pemba. Covering a wide expanse of disciplines, the exhibition includes drawings, sculptures, paintings, woodcuts, linocuts, serigraphs and etchings.

A challenge to existing ideas of South African art history, the exhibition aims to inspire a more critical meeting with these artists whose works have been historically neglected. An important theme of the exhibition includes the examination of the contested label of “township art”, critiqued for boxing Black artists from this locality.

Curated by Dr Same Mdluli, Standard Bank Gallery manager and curator, the show’s curatorial strategy is influenced by The Images of Man. Here the author had begun organizing the works into a chronology, not specifically on how these works came into the Fort Hare collection, but on how Black art history was developing in the country. Identifying reoccurring themes within the works, Dr. Mdluli structured the exhibition according to subject matter that comes through in the artworks. References in the works include but are not limited to spirituality, belief systems and the township.

Abstraction. Moments of everyday life. Resistance art. Optimism and hardship. Spanning over three decades of the collection, the show represents a part of an era in which South Africa was known for challenging conditions as a result of colonialism and apartheid, the remnants still visible today.

Dr. Mdluli expands on the themes of the exhibition by unpacking the contested label of “township art” explaining that these artists were placed within “an already existing narrative”. She continues to say “I did not want this project to come across under [a] revisionist notion. I’m not revising anything about history. I am simply, being provocative around our understanding of what constitutes South African art holistically given that there was all of these other divisions and segmentations and categorisations of where artists sit. So in a way this exhibition, through the themes, it’s suggesting ‘what would a South African art landscape look like if it was inclusive of all these other aspects?’. That’s why I’m going back to the themes. The notion then of ‘township art’ is I think conflated with all of that discussion and debate around how it has been categorized and classified in a way that has nullified the subject matter that some of these artists were dealing with.”

Referencing Dumile Feni, Dr. Mdluli explains that when Black artists are spoken about they are often placed in comparison to Western artists instead of giving Black artists their “own agency and ability and technical skill tree to make art”. This can be seen when looking for example at the way in which Feni was called the Township Goya.

Pin pointing another theme of the exhibition Dr. Mdluli speaks to the way in which religion can be politicized. This comes through in the context of these works as these artists were questioning an oppressive system asking “‘how could there be a God and allow apartheid to happen?”’. She continues to say that “essentially the kind of philosophical questions that Black theology seeks to interrogate and how Black theology drew on Black Consciousness for the very same reason of self-love, self-affirmation. That’s why I think Black theology tends to be sometimes in the rubric of politics and not so much religion. It’s an under studied researched area. Because there were a lot more artists interrogating those kinds of questions around religion, religion in an African sense, religion in an oppressive state.”

The works of Ernest Mancoba, George Pemba, Gerard Sekoto, and John Koenakeefe Mohl amongst others are placed in a union acting as a testament to these early modernist masters’ works and how they have added to the modernist practices of the early twentieth century. Provocative in execution the exhibition similarly brings up questions such as how is modernity defined? and why are these artists left out of the rubric?

Ephraim Ngatane, Gladys Mgudlandlu, and Winston Saoli seem to be working with postmodernist ideas characterised by each artist’s distinct approach and meaning given to process. The point at which art and ideology intersect is made physical by artists such as Paul Sibisi, William Zulu, Madi Phala, Thami Mnyele, and Lucky Mbatha. Artists such as Dumile Feni’s work has reached audiences across the world acting as an influence on many other practitioners (as he lived in both the UK and the US his work is more internationally celebrated). A section of the exhibition is dedicated to Feni’s repertoire indicating his mark on style, form and aesthetics.

“…one of the things that David Koloane has been always adamant in, and I think what was made distinct is the fact that he was very vocal about contesting this notion of the authentic African artist. And how do you define that and who defines that more importantly. That there was this notion around art making and the concept of what art is that is very much based on a Western notion and understanding that insisted that African artists had to make art of a particular kind that spoke about their Africanness.”

Speaking to the thread of stories that is interwoven into the exhibition Dr. Mdluli states that as a part of the curatorial approach a concerted effort was made to move away from the way in which Black artists have historically been spoken about. As there is a tendency to focus on their biographies as opposed to interrogating their works and what informed their practice.

A Black Aesthetic: A view of South African Artists (1970 -1990) is indicative of the influence exhibitions have on visibility–of both artists and artworks, works in an archive that has been kept from public view is removed from consciousness. By placing it within the frame of a gallery it is made more visible and brought back into conscious thought. In turn, the works are opened up for a new generation of art devotees to appreciate.

A Black Aesthetic: A view of South African Artists (1970 -1990) will be on display at Standard Bank Gallery from 22 February – 18 April 2019.

Follow Standard Bank Arts on their social channels to partake in their #CaptionChallenge – create contemporary captions for artworks! To learn more about the artists and their artworks follow #KnowYourArtist on Standard Bank Arts’ social media pages where information about them and their individual practices are shared.

Walkabout Dates: 23 February, 9, 16 and 30 March, 6 April. All walkabouts will start at 11 am.