“The home garden also becomes a space of domestic labour of pleasure. The domestic becomes the site of productivity but also of leisure and enjoyment. The garden, therefore, becomes a space of claiming the power of the domestic, of intimacy and home-ness.”

— Ejaridini, MADEYOULOOK

The garden evokes ideas of growth, renewal, cultivation, care, and life. But it also gestures to land and brings to mind dispossession, colonial violence, plunder and pillage. In her 2020 article for the Architectural Review, ‘Home ground: the garden as a site of colonial critique‘, architect Ilze Wolff reminds that, “the garden is a site of memory etched by racial violence…” It is this tension of the garden as a space for leisure and aggression that makes it generative — an entry point to thinking about claiming space.

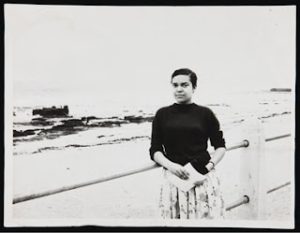

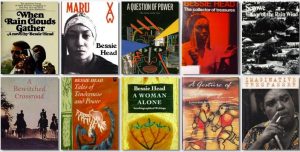

In July of this year, Ilze Wolff crafted a generous and elaborate sound garden in celebration of what would have been Bessie Head’s 85th birthday. Head, of course, is the brilliant South African writer who made a new home in Botswana and brought us dynamic and impressive titles, including; When Rain Clouds Gather (1968), Maru (1971) and A Question of Power (1973). This thoughtful and beautiful offering coalesces music, readings and excerpts of Head’s own voice through interviews. Contributions in Wolff’s tender sound garden reach across geographical boundaries – from South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe to Japan – with readings by Jess Myers, Wame Molefhe, Michelle Renyé, Moses Serubiri, Mmakhotso Lamola, Nombuso Mathibela and Hitomi Yokoyama.

As an ode to Head, the sound garden situates the writer as an impactful agitator and instigator and what she might have termed, “a contributor to human thought”. With a gentle and quiet voice, Head’s views were sturdy (and sometimes thunderous) and described as, “having the kind of depth that is [frankly] lacking from most African literature”, by Zimbabwean writer Dambudzo Marechera. She didn’t waver, as demonstrated in her analysis of Gladys Mgudlandlu’s work under the title; ‘Gladys Mgudlandlu: The Exuberant Innocent’ – a poignant observation of how and why Mgudlandlu’s work might have been more palatable to collectors compared to say that of the sharp Ephraim Ngatane; “Ngatane is annoying” as he reminds people that, “townships are nasty places”.

Head’s fondness for plant life is well documented, Wolff notes, “Tom Holzinger, a member of the Bessie Head Heritage Trust, explains that Head planted an elaborate productive garden in the yard of the house. At the entrance, she planted two rows of gooseberry bushes, from which she would make jam and sell it to make extra money. She collected seeds and experimented with various plant species.”

Through their art installation and garden project, collaborators Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho of MADEYOULOOK, propose Black urban gardening as an existing practice that takes colonial inheritance and remakes it, creating a different set of implications and practices that are of deep value. Head left South Africa as a refugee and found ways, under difficult conditions, to reconfigure homeness. She did this, among others, through her writing and her interest in agriculture (on a large and small scale).

Writing about the politics of voice, Slovene philosopher Mladen Dolar asserts that; “We might be rather surprised to learn that the very institution of the political, depends on a certain division of the voice, a division within the voice, its partition.” And yet politics can in fact be read alongside poetics because language itself is wrapped in voice. To find the voice of Bessie Head and to hear it enmeshed with that of her contemporaries – Langhston Hughes, Dambudzo Marechera, Gladys Mgudlandlu, Ephraim Mojalefa Ngatane – is to experience the power of co-citation as co-creation.