*This essay forms part of Bubblegum’s Collaboration with Bag Factory and their visiting curator from Uganda, EM Mirembe.

It is the first part of Joburg based art critic and Azanian Philosophical Association member Athi Mongezeleli Joja reading of apartheid former president, F.W. de Klerk, pre-recorded “last message” video.

Those who have wronged must be ready to make amends they can. They must be ready to make restitution and reparation. If I have stolen your pen, I can’t really be contrite when I say, ‘Please forgive me’, if at the same time I keep your pen. If I am truly repentant, then I will demonstrate this genuine repentance by returning your pen. Then reconciliation, which is always costly, will happen.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, 1990.

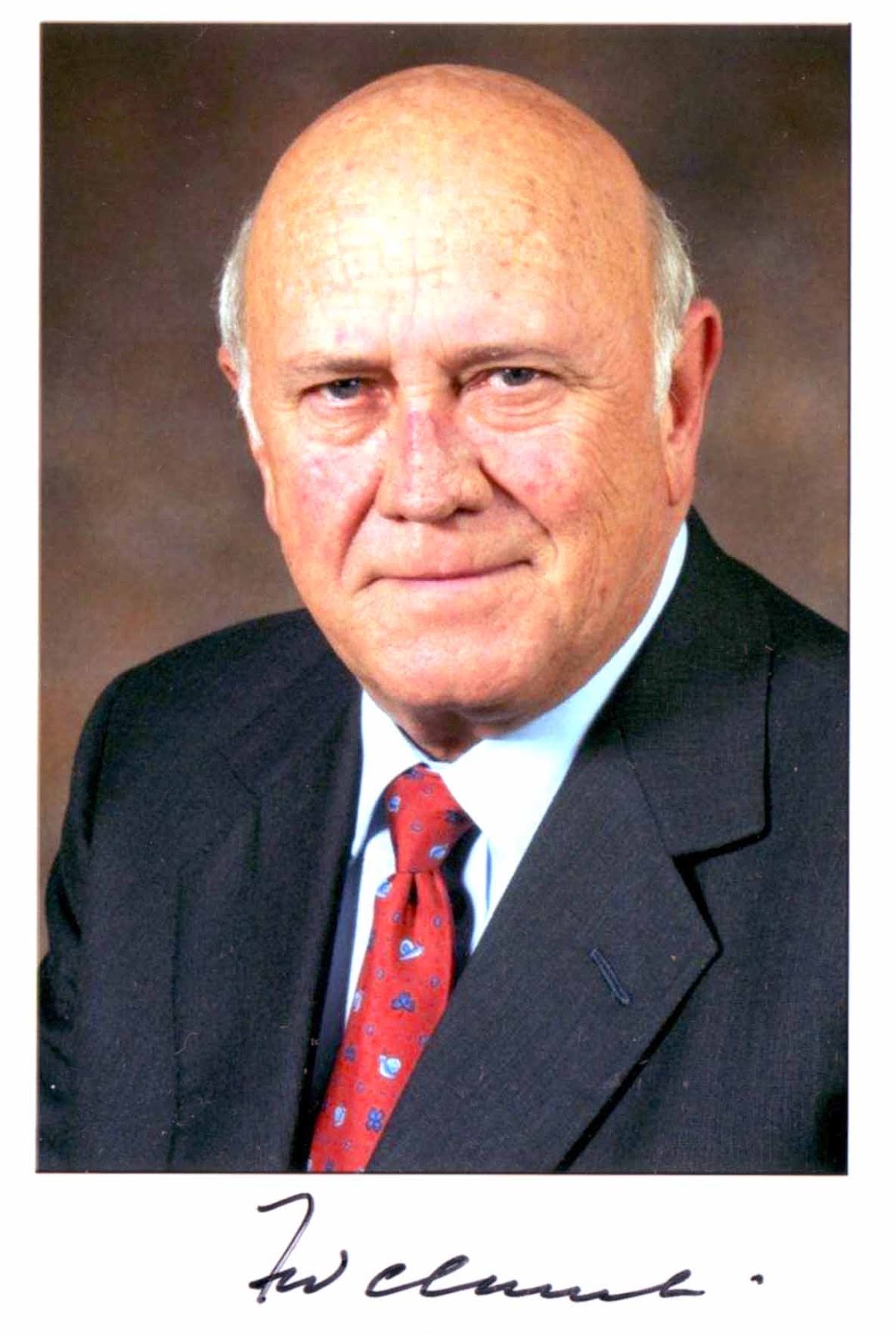

When the media announced the death of apartheid former president, F.W. de Klerk, they also shared a pre-recorded video of his “last message” apologising for his part in the racist regime.

The message itself is clear and to the point: ”I, without qualification, apologise for the pain and the hurt and the indignity and the damage that apartheid has done to black, brown and Indians in South Africa.”

The former statesman looks gravely ill, emaciated, and exhausted in the video. The news of his battle with cancer was first announced during his 85th birthday celebration, just a few months before his death. Admittedly, this is among the many public apologies de Klerk has made over the years.

However, given that his previous “apologies” were offered on “…behalf of…” the racist state policies, the Party etc. — to crimes reluctantly admitted to with a conditional acceptance of responsibility — this last apology fairs comparatively better in performance, perhaps precisely because it was recorded at death’s door and released posthumously.

Consequently, it allows us to properly engage with what Sara Ahmed might call the non-performative admissions of whiteness and their elaborate choreography. On the other hand, when studied further, the video’s labour extends beyond the display of contrition as its theatricality is greatly emboldened by the figurative artefacts that punctuate the visual plane.

This article argues that when the viewers temporarily suspend the labour of hearing and begins to dart their eyes between the amenable artefacts in the background — a portable sculptural ornament, a portrait of De Klerk and his wife, and lastly the pre-eminently in/visible portrait of a Black woman in a yellow scarf — De Klerk’s “message” comes out more strongly.

The article is particularly interested in the critical role played by the placement of the native woman in the frame and the kinds of signifying interventions she makes within the context of the apology. The problem of white apologies vis-a-vis Black forgiveness has its own discursive and political complexities but given the scope and space, this article will not pursue that line.

Neither will this article substantively decode the verbal apology or the debates it generated. Rather, it is preoccupied with the visuality that we’ve pretended — by our collective silent treatment — does not merit any interpretative attention.

Looking at the video from that angle, it also becomes apparent why commentators have hardly said anything about it besides the said last message. Is it because they/we are partly prepossessed by it or worse, potentially blindsided by its elusive and unimposing cinematographic comportment?

Or perhaps it’s not so demanding, and it was merely a deliberate recusal, typical of the tendency in political discourse to reduce anything remotely falling outside of its jurisdiction — especially that which resembles culture — to mere accessory?

A discursive foreboding in post-apartheid cultural thought for politically inclined matters? The video is singularly grasped as a straightforward apology; meaning, the last message is merely incapsulated in and by verbal enunciation. The visual choreography — so subtle but nevertheless very much present — fades into in-existence.

In other words, mood, size, lighting, camera movements, posture, background, props, body language etc.— elements that form part of the video — do not easily call into critical attention their psycho-informative power.

We see them but not enough to read them with cautiousness and intentionality they bring into the visual plane. It is perhaps through what seems like a calculated focus in their proportional and spatial arrangement that provides a gateway into what, in this case, might unravel an elaborate makeover plan. Put differently, its attempt to derange and discombobulate our perceptions of de Klerk, thereby humanising him, becomes all the more apparent.

The video attempts to reconstruct our perceptions of de Klerk by supervening the prevalent images, thoughts, and associations that are invoked by his name. These are the largely anti-racist, Black perceptions that have remained unconvinced by the post-1994 statal veneration of de Klerk as part of our national political royalty, sculpturally typified in the Nobel Square in the V&A Waterfront, Cape Town.

This is the last message addressed to the people of South Africa. To my dear wife and family, I will say goodbye in a different way. Our country faces so many challenges of a serious nature, I hold firm opinions about all of them but decided to keep this message very short and really focused on two issues…touching me and touching the country.

So begins the message. The video shot is in medium, portrait form; it profiles the subject to visually capture his emotions, his interiority. A cursory study of de Klerk’s pictures on the internet often portray a man in an objectively impersonal and austere political context. In these pictures, the image and personality of the leader is purposefully devoid of individuality since he must appear and speak on behalf of something other than or beyond his personal capacity.

Frigid, sombre, restrained, and monumental are some of the pictures’ general traits. Although his body is failing him, the mood captured in his last public (also read posthumous) video is a warm, inviting, and optimistic one — it is homely and personal. That we see him at home, I presume, not only paints a different picture of the man but it also hypostatises the haptical valance of redemption that subtends his message.

In other words, the reference to tactility — to the vicissitudes of his touch — plays into the exceptionalistic narrative of de Klerk’s presidency within a pantheon of apartheid leadership as it also casts him as an indispensable bridge of virtue that heralded us into the “new” South Africa. In this sense, home not only represents the domestic space but also conquered South Africa which he’s praised to have allowed Blacks to enter.

Furthermore — as a moving image, and not a photograph — each widening and narrowing of the shot in the video, in varying subtle degrees, includes or excludes details in the background. To his right-hand side, de Klerk is flanked by a couple of very curiously assembled but corresponding personal pictorial items:

- a minuscule sculpture of two figurines embracing,

- a cosy portrait of himself and his wife and

- finally, a portrait of a Black woman in a yellow head wrap.

With the red lamp shade on the far side radiating a soft glow, its gentle luminescence shyly dancing all over the dresser and these nearby pictures, the light bounces around the right side of the subject’s face while another, invisible, source tenderly beams the left.

This ominous glow engulfs de Klerk in a halo of light, that it almost depicts a picture of a sickly angelic figure. Despite popular reservations, however, the message passed herein — not only by the subject’s own lips but also by the total visual apparatus — seems solely invested in allaying all doubts about de Klerk, the man.

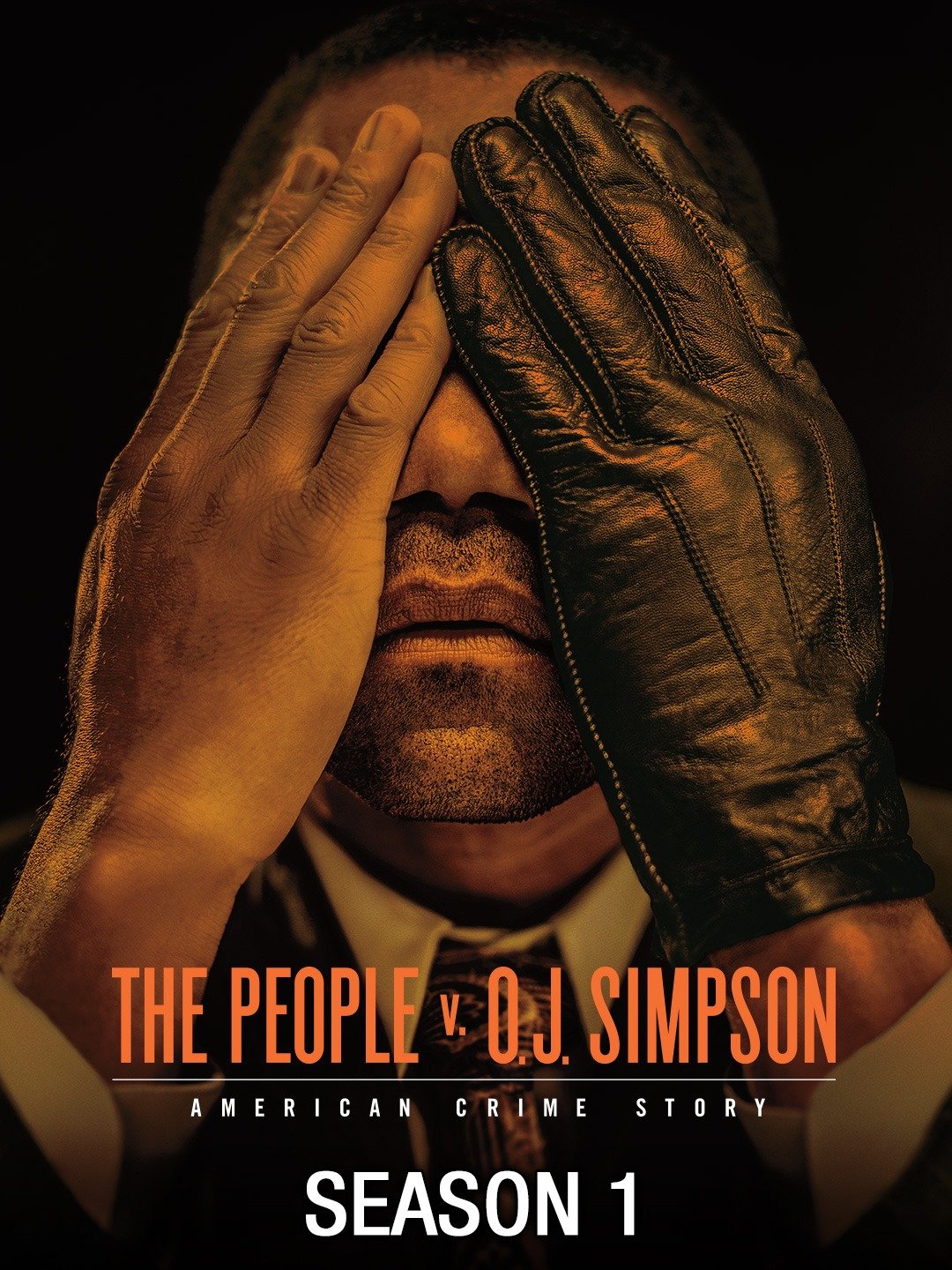

In the recent Netflix biopic called, The People vs O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story, based on the controversial double homicide case that involved the now late sportsman O.J. Simpson, the defence team underhandedly tinkers with their client’s home during the jurors’ visit into the accused’s residence in the leafy suburbs of Los Angeles. Though Simpson is a pre-eminent Black sportsman, his lack of loyalty and uppityness towards the Black community is a cause for concern to his legal team.

Therefore, in order to manipulate the perceptions of Black members of the jury to his client’s favour, lead attorney Johnny Cochran (played by Courtney B. Vance) decides to change Simpson’s home into an African-themed interior decor making Simpson appear relatable to the Black jurors. This example speaks to how belonging — in this case, domestic space — can be subjectivising.

To supplement an old adage: “show me your home and i’ll show you who you are!” While Cochron’s sleight of hand was to “prove” his client’s “innocence,” it seems to me that de Klerk’s mise en scene, set in the context of an apology, undoubtedly intended to convey a degree of relatability: and herein lies the rub!

Here, familiarity does not intend to breed contempt. If anything, it intends to solicit trust. This staging of the grand scene of repentance, as it were, strips De Klerk of all his accolades and stately qualities — member of parliament, former president, Nobelist etc. — reducing him to the bare-minimum of the everyday.

An ordinary man? The observer’s shift in focus from the spectacle of the apology in the foreground to the quiet, everyday cultural objects in the back, isn’t to disregard the former but rather, to explore how it is further reconfigured, contextualised and emboldened by the latter.

In other words, while the apology draws us into recompense, the pictorial mise en scene of the domestic scene provides a palatable context of relatability. The pictorial items included here, by virtue of their quotidian presence, both locate and co-locate De Klerk at home and with the commonplace assumptions informed by being at home. The representation of domestic and day-to-day scenes in genre painting and in expressive cultures more generally, turn to the mundane, innocuous and nondescript to indexicalise both authenticity and truth.

Click here to read part 2 of the article.

Athi Mongezeleli Joja is an art critic with vested interests in the intersection of Black radical politics and visual cultures. He is a member of the Azanian Philosophical Association.

Portrait of Athi Mongezeleli Joja.