*This essay forms part of Bubblegum’s Collaboration with Bag Factory and their visiting curator from Uganda, EM Mirembe.

There are two types of rulers: the artist who provides and sustains the fundamental ideas, the foundation of society; and the political chieftain, who comes to power with the aid of his soldier and rich business brethren who merely puts these ideas into practice in ruling or misruling society.

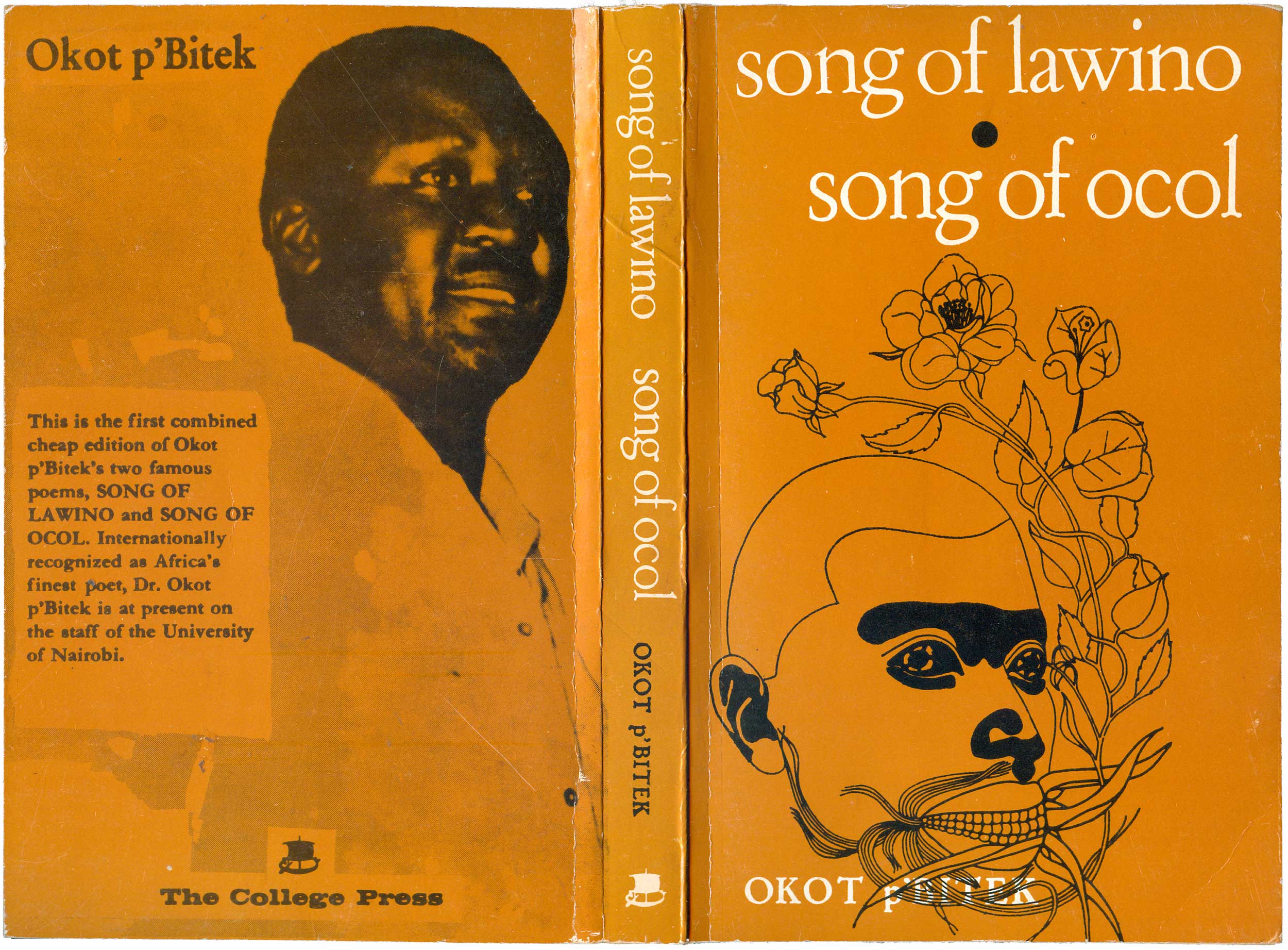

Okot p’ Bitek

Long before the Ugandan government sent feminist scholar and poet – Dr. Stella Nyanzi – to prison for her provocative Facebook poem about President Yoweri Museveni and the First Lady, playwright Byron Kawadwa was taking the Ugandan performing arts by storm in the 1970’s. The era often evokes nostalgia for what is said was fast becoming the blueprint for what the Ugandan arts could achieve — a decolonised, politically conscious culture.

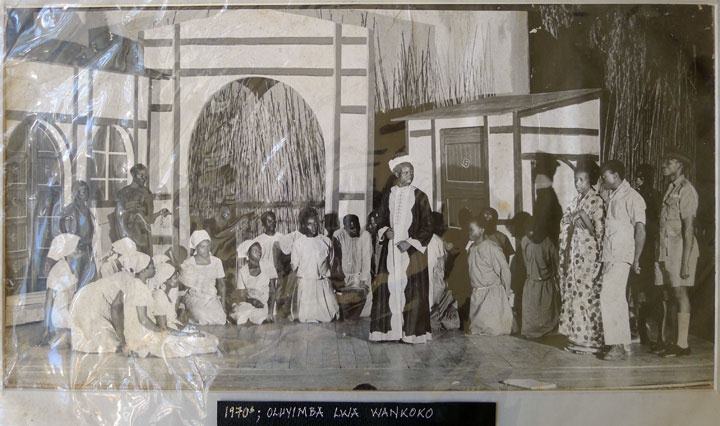

At the time, former Ugandan dictator Idi Amin was closing in on government critics, forcing some artists including Okot p’Bitek into exile. Kawadwa continued to push back against oppressive regimes through his work. It is presumed that it is the political satire he wrote on Amin’s regime, Oluyimba lwa Wankoko, that sealed his fate. In 1977, Kawadwa was kidnapped by state agents at the Uganda National Theater where he was the then artistic director. He was murdered and his body dumped in Namanve forest.

Both Nyanzi and Kawadwa, seemingly as a last fervent resort, practiced radical resistance of the respective oppressive governments through the mediums they had available to them — their art.

Oluyimba lwa wankoko, at the Uganda National Theatre 1970s.

Portrait of Dr. Stella Nyanzi.

Neoliberalism takeover of the arts

The ways in which power and oppressive systems hit back at the arts have since morphed into other forms. For a generation that has come of age in a political economy characterised by an increasingly aggressive neoliberalism, we are now forced to contend with corporate culture takeover of something so profoundly human in an unaltered form, as art.

There are three major ways for a creative artist to be widely supported and recognised, today in Uganda. The first one is one that which Nyanzi and Kawadwa have known so well: if their art form provokes the political elite enough to garner a large public following. Once the masses notice and interact widely with this work, it is almost certain that state violence and persecution will occur. When persecuted, their Ugandan audiences, legal teams, colleagues and Western allies alike shall then amplify their work and actively or passively speak against the government’s violent response.

The second and third are thus: if the artist has attained an arts degree from a Western learning institution or been commended by a platform there, and if their art has become a job. Both these forms of creating art have an economic value attached to them, which is the only way they are useful to rapid privatisation policies which the State romanticises with terms like: steady progress, prosperity for all, the promise of reaching middle income status, among others.

The danger of the latter is that we are then left scrapping for the leftovers from employment structures that are already predisposed to view the arts as unimportant, therefore not of much worth. On the other hand, recognition of a higher level training in the arts, or validity that is exclusive to a nod from the West is an illusion of meritocracy. In reality, the financial, social, and cultural capital requirements in the process of attaining that recognition disqualify the majority of artists from the onset.

Stuck in the hamster wheel of corporate politics, artists grapple with conformity, mental exhaustion and a lack of financial security. There’s no time to cultivate critical thinking — a stimulant for artistic expression. There’s certainly little room left to employ that art in political protest, given the implications.

The inauguration of William Richard Tolbert, 19th President of Liberia. Tolbert and Idi Amin, Ashmun street, Monrovia, Liberia, 1976.

Fifty shades of the leopard’s wrath

At the height of election campaigns leading up to the 2016 Presidential elections, violent clashes ensued between the supporters of the President and those of Museveni’s longtime collaborator Amama Mbabazi who had entered the contest as an independent candidate.

In an address for the following week, an angry Museveni likened the trouble awaiting those ‘thugs’, opponent’s supporters, to the one that would befall anyone who put their hands in the anus of a leopard. To borrow that reference, artists like Nyanzi and Kawadwa have across regimes in the history of Uganda put their hands in the anus the leopard with artistic expression. On those occasions, despots like Amin and Museveni have retaliated with impunity and violence.

Yet many, much more subtle attacks have been made on the arts in Museveni’s thirty five year rule. As far back as the early 2000s till today, the President, and later the First Lady who he appointed Minister of Education have been on record disparaging the arts, while supposedly promoting the importance of sciences.

Women wait in front of their food stalls for the final result of the presidential election in Kampala, Uganda, on February 20 2016.

In 2014, the President who has been touted as a champion of science called upon government funded Universities to develop more science courses and drop ‘useless’ arts. Earlier on, secondary school parents and students alike had already been caught in this narrative.

In 2008 when I sat my Ordinary (O)’Level examinations in Trinity College Nabbingo, it was common to overhear parents at the teacher’s table berating their children for performing poorly in science subjects such as Chemistry, Physics, and Biology.

The parents would then seek teachers’ guidance on how to help those students improve, so that at the Advanced (A)’Level, they would qualify for a sciences subjects combination. The efforts were driven by the growing campaign for sciences that labeled them “more marketable”. As such, parents who naturally want(ed) their children to do well within the economy did everything they could to make sure of it.

The President’s dismissal of the arts and humanities can be taken simply as those of a “champion for the sciences”, yet the government he heads doesn’t seem to be eager enough to have medical workers fairly compensated. Throughout the pandemic so far, he has repeatedly highlighted the superiority of science as evidenced in how Uganda managed its COVID-19 cases.

In April 2020, when Uganda began registering and treating patients, Museveni thanked health workers in one of what would be many national addresses, saying he was proud of them. In response, medical workers, through their Secretary General, asked that the President translate his appreciation into better salaries and allowances. In December 2021, medical workers laid down their tools in protest against salary arrears and poor compensation.

The disparaging remarks on the arts can also be interpreted as a deliberate attempt to sabotage a field that poses a threat to his rule. By encouraging support of the sciences over the arts, he is also reinforcing a message to donors and the larger economy that the arts are not profitable, therefore not worthy of attention and investment.

Police in Uganda arrest suspected protesters after they demonstrate their support for opposition leader Kizza Besigye, 2016.

Radical community as a response

To counteract the workings of neoliberal economics and a perpetually repressive state, artists must equally employ radical methods of community and collaboration. Consuming each others’ work, and participating in its creation – together. Reaching out to one another, teaching, and learning from one another.

More importantly, we should work towards creating the spaces we so badly hoped for from the systems that have instead disfavored us. Spaces in which we are valued both as individuals and artists – seasoned and emerging. Where space is held for us all regardless of what part of the journey we’re at. In Uganda, the Writivism Literary Initiative convenes a community of emerging writers, hosting workshops, publishing anthologies and holding literary awards for African emerging writers.

In a society where the art of writing is only widely encouraged if one is practicing journalism – this community that supports both fiction and nonfiction writers, established and little-known, holds promise for generations of literary artists who are charged with steering transformational ideas into the minds of society. Writers that might otherwise be considered ‘unqualified’, and therefore disregarded by neoliberal systems.

Panashe Chigumadzi with the Gayaza Girls at Writivism 2019.

Artsy, a web series on Instagram/IGTV featuring conversations with creative artists, centres the human beings behind the arts, showing audiences the processes, stories and reflections of the people that create art. By carving out an alternative media space for the arts, the series seeks to build a great network of young, talented African artists of our generation. Utilising the digital tools available to gain relationships, and collaborate for social change.

As a generation, our work is cut out for us: we have a responsibility to retrieve the arts from the jaws of both the leopard and capitalist structures. We are tasked to transform art into a way of life, a means of fostering community and collaboration in transforming our societies.

But it cannot happen in isolation. One nomination or award for any creative artist might be a win for us all, but spaces that afford us collectively a platform to tap into our respective artistry is the truest measure of success, one that ultimately saves the arts.

Edna Ninsiima is a Ugandan feminist writer, editor and communications practitioner. Her writing has been featured in the Daily Monitor newspaper in Uganda, Lakwena a Feminist publication for which she is co-founding editor, Andariya Magazine, a bilingual web publications based in Uganda and the Sudans, the Suedwund Magazin, her blog, beingedna.com, Bankra an online platform dedicated to exploring and navigating Africa, Q-Zine. Her short story, ”Finding Freedom ” was published in the Writivism Anthology, Odokonyero.

In 2020, Edna was nominated for the African Women Leadership Awards, in the Literature Category.

Portrait of Edna Ninsiima.