Much excitement fills the air of Makhanda, from its highest peaks at the Monument to the Valleys of Rhodes University, as the first in-person National Arts Festival takes place following the surge of the Covid-19 pandemic. Indeed, we were all ready for a return to the theatre space. That excitement found its way into the Box Theatre, where 2021 Standard Bank Young Artist for Theatre Thando Doni would be showing his directorial work in Ngqawuse [The Death of a Nation].

What followed was not just an immersive experience back into a rich theatre culture, but a return to a hurt which precedes us.

The show derives its name from the Xhosa prophet, Nongqawuse, who is infamously remembered for being the impetus of the cattle killings of 1856, leading to the subsequent famine of 1857. Doni looks back in history to find one of the first wounds to a culture, which go on to never quite heal today.

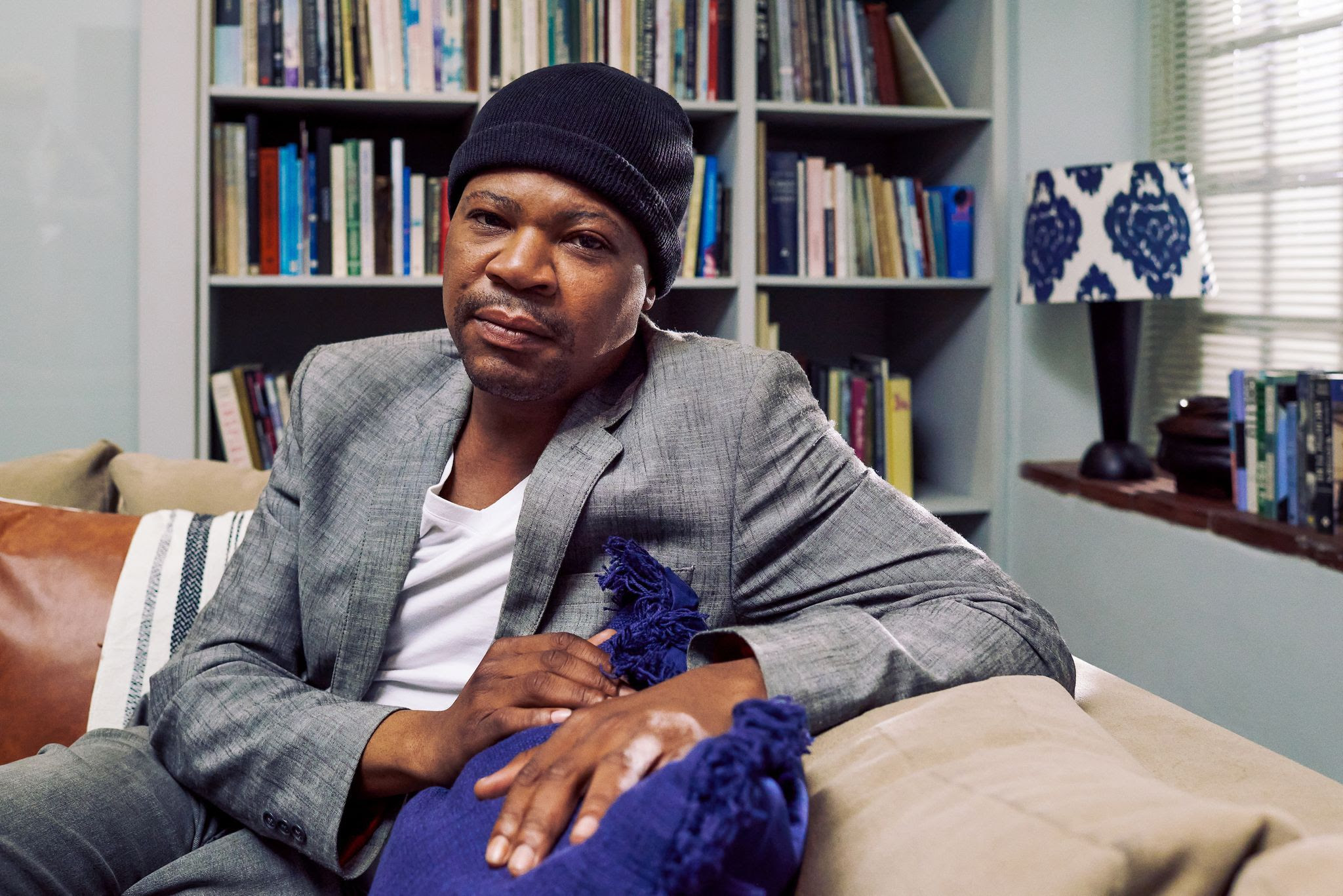

Photograph by Mark Wessels

The play, performed almost entirely in isiXhosa, confronts the audience with a refamiliarising context. The South Africa that exists today, and specifically much of the pain and devastation that exists within the Eastern Cape, is not without a story. These struggles aren’t natural and inevitable parts of Black history, but a result of desperation in the face of violent European colonialism.

Easily, one could imagine how this play would go on to contribute to a disdain for Nongqawuse. Yet, in a masterful feat of storytelling, Doni shifts the lens of history from being focused on Nongqawuse and more on the family structure that was inevitably affected. This wouldn’t be possible without the moving performances of the cast and ensemble, including the performance of Nongqawuse played by Standard Bank Young Artists award recipient Chuma Sopotela.

What the cast manages to do is perform true intimacy and community on the stage, showing the shifting dynamics of friends-to-lovers-to-life-partners. It is a beautiful, but not invasive insight into a true home.

It is a challenge we’re faced with when asked to consider major historical moments, not from the macro lens through which history is often told. In big statistics, in sweeping statements, and many years condensed by a single dash. Within the years 1867 – 1857, tens of thousands died as a result of that famine. But Ngqawuse urges us to zone in, get closer and feel the effects of a multi-faceted betrayal. A true home which goes on to know true pain.

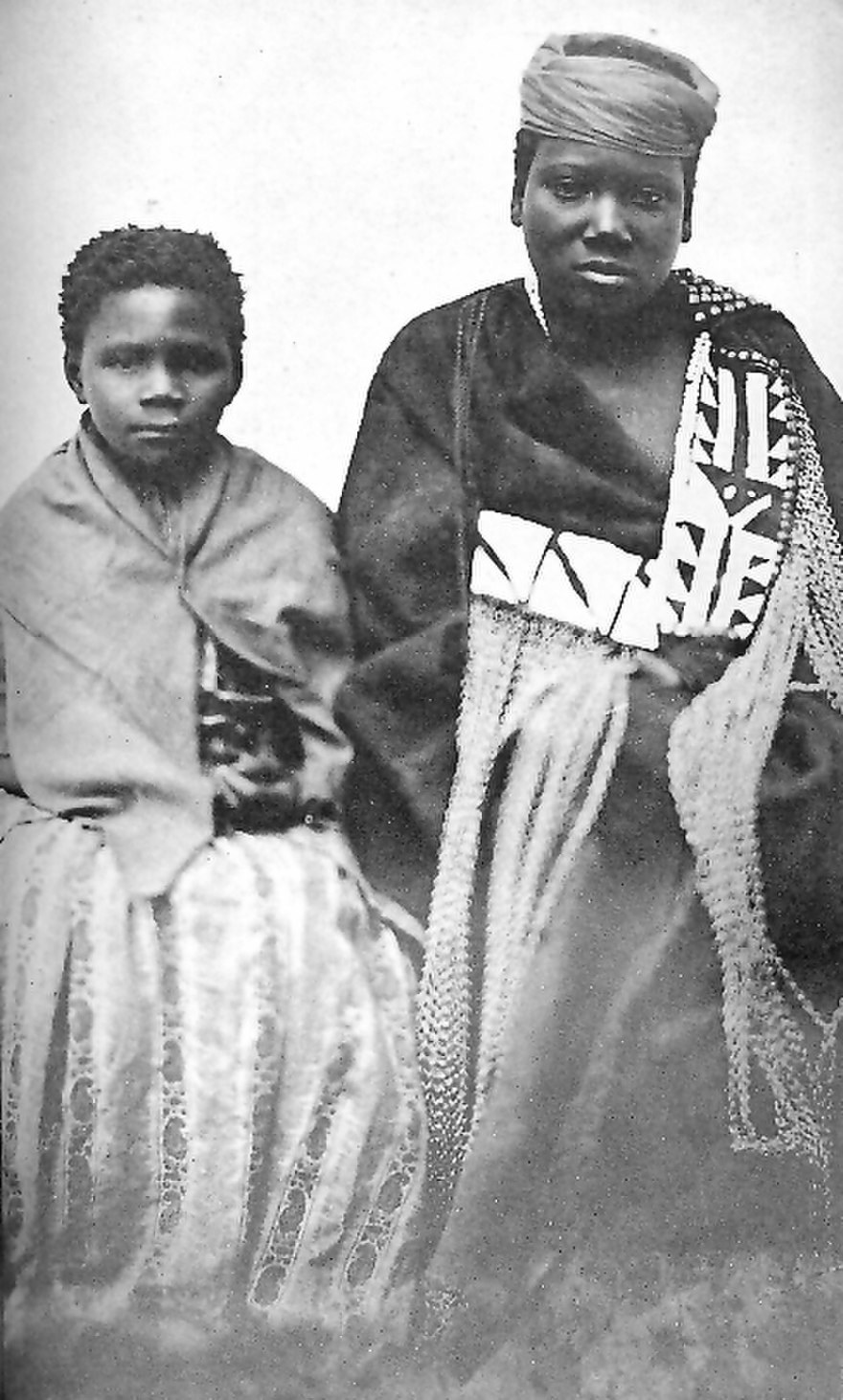

Photograph by Mark Wessels

At the end of the play, in a beautiful solo moment performed by Indalo Stofile, it is as if a mirror is held up to the audience. As the lights go out, and the audience is once again in blackness, we sit with a scene that reflects the lives we live today. The familiarity in which many of our mothers cope with various griefs, in a way which would be so unfamiliar to our ancestral mothers.

Doni shows us where some of our wounds come from. The wounds don’t hurt in the same way, as when they were initially inflicted. In some moments, one might just be able to forget that it ever hurt. The scab is there but the distance between infliction and the present grows every day. But once in a while, that wound is touched and a sting comes back and reminds us we have been hurt. It is a reminder that where skin broke, a part of us died.

It is this wound and this death that Doni and the team of Ngqawuse touch on in a way that is so intimate and genuine.