It comes as no surprise when yet another debate over identity especially race & ethnicity arises in our public consciousness and conversation.

As many nations grow and morph from their distinct yet sometimes similar histories, people who feel in any way destabilised seek to establish who they are and how they would like to be perceived by the world around them.

There is currently an ongoing debate happening online, where Black Americans or rather African Americans maintain that people with direct African nationalities should not or can not label themselves as Black.

To truly explore this claim, one needs to re-engage with helpful definitions of race, nationality and ethnicity.

Race: any one of the groups that humans are often divided into based on physical traits regarded as common among people of shared ancestry.

Nationality: a group of people who share the same history, traditions, and language, and who usually live together in a particular country.

Ethnicity: an ethnic group; a social group that shares a common and distinctive culture, religion, language, or the like.

The conceptualisation of race is one that many think is quite obvious because of its association with physical attributes, mainly skin colour, however many others have concluded it to be a “social construct”.

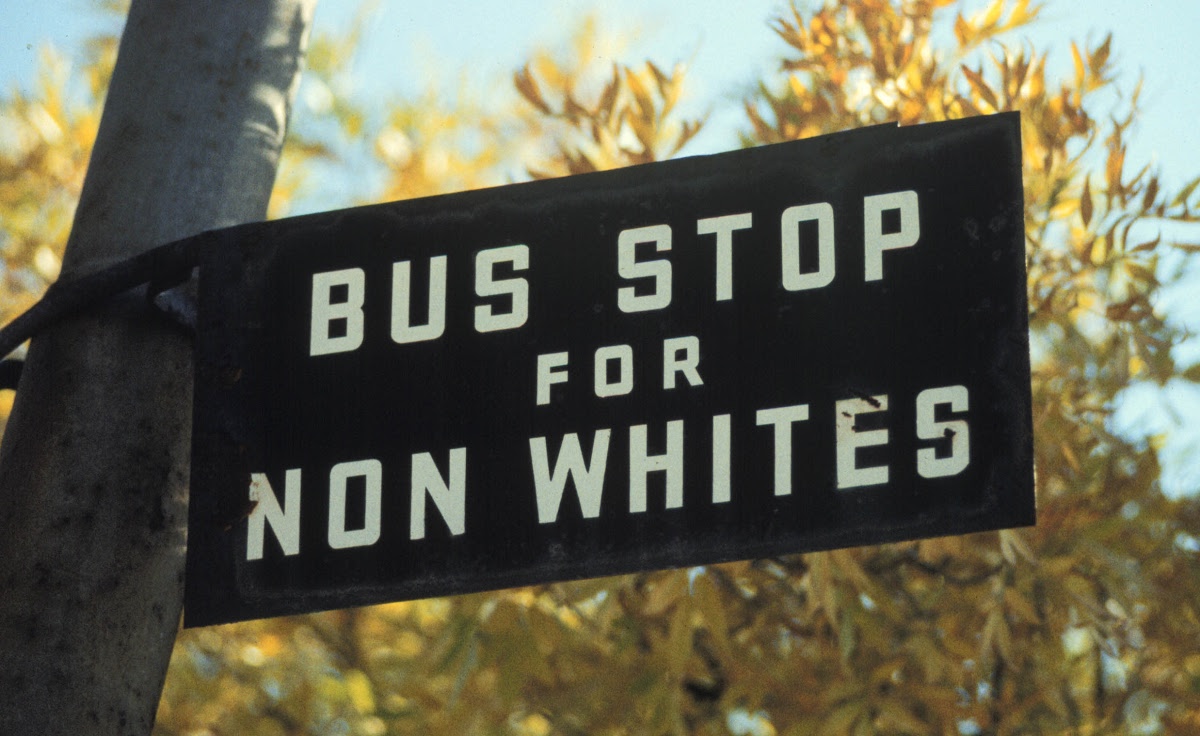

Race is not a biological fact but rather it is a social construct that has become historically and socio-politically naturalised through institutions of white supremacy, organising people into degrees of humanness. A very apparent example of this kind of classification was during apartheid in South Africa where spaces were stipulated as:

“Suburban station for non-whites”

“Caution beware of natives”

“Europeans only”

“Blanke gebied”

“Net blankes”

An entire institution which relied on the classification of different kinds of human beings in order to create separation and enforce oppression.

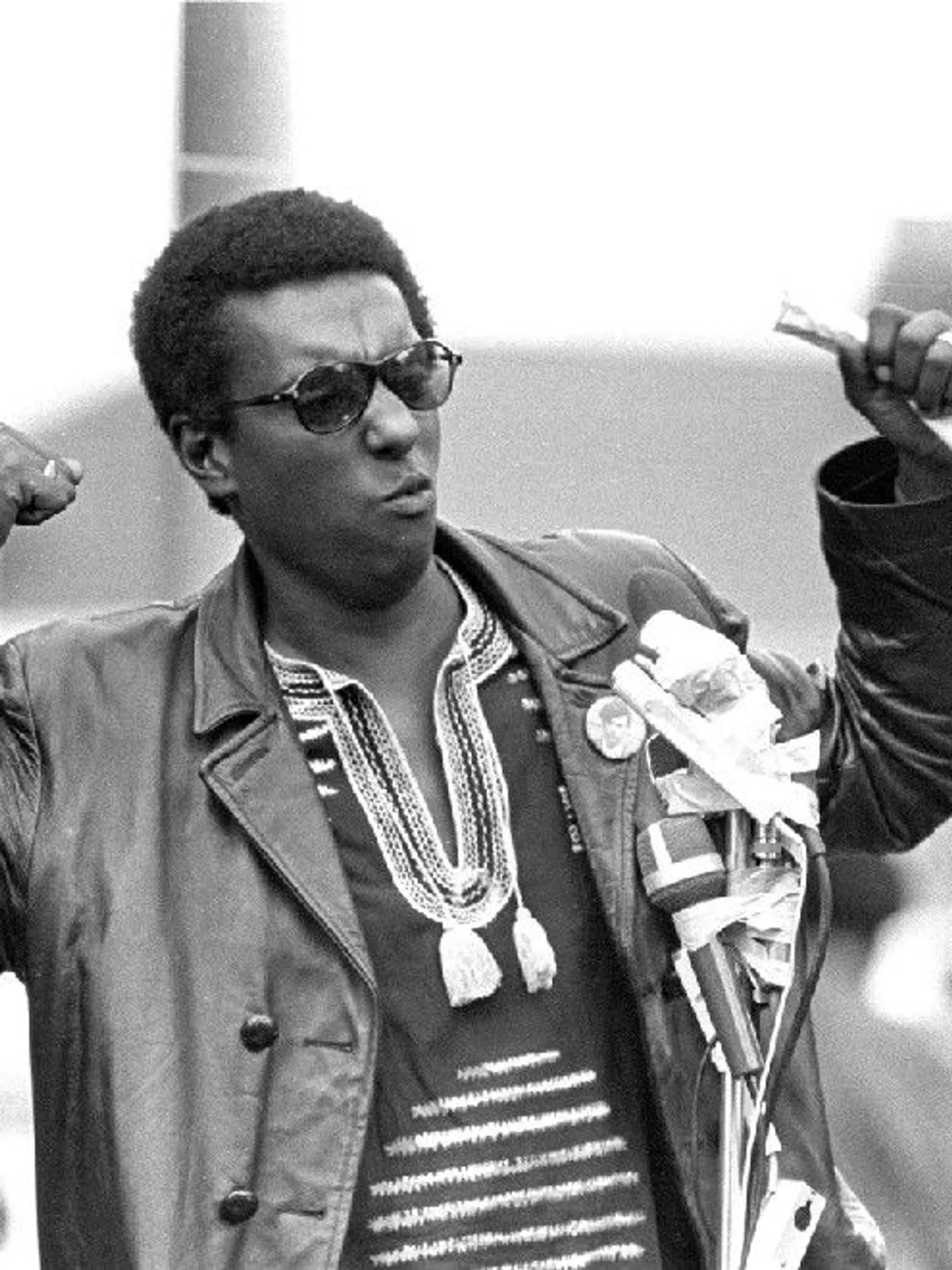

Similarly, this kind of thing happened in the United States, with the criminal act of forcibly taking and displacing African people for the purpose of enslavement and then forcing them into a segregated system — a system that completely enforces the strategy behind white supremacy.

A big part of this strategy is to also ensure that certain terms create a vortex of societal humiliation, degradation and dehumanisation of darker skinned people — terms like the k-word (in South African context), n-word (in US context), negro, coloured (in US context) etc. all categorised under the umbrella of racial slurs and are not appropriate to use in society today.

The rejection of these labels is an act of rejecting white supremacy and racism/racial abuse.

Upon further research, some scholars, usually African American scholars, deny and disapprove of the use of the term “Black” as they view it in the same light — saying that African American is more suitable as it honours the African ancestors that were enslaved in the US but also the Americanness that is notably due because of their positionality within the grand scheme of the US, whereas Black is a term that Europeans or white people used to demean people of African origins, especially where the synonyms of the word are concerned; dark, tragic, ruinous, dirty, stain, soil, disastrous etc.

However, in many other contexts, in fact, probably the most popular understanding of the term “Black” (blackness) is that it is a racial term used to describe a specific racial identity. Usually people with darker skin, or African ancestry.

The non-acceptance of Black being used as a racial term to describe African nationals is one that piques a certain curiosity.

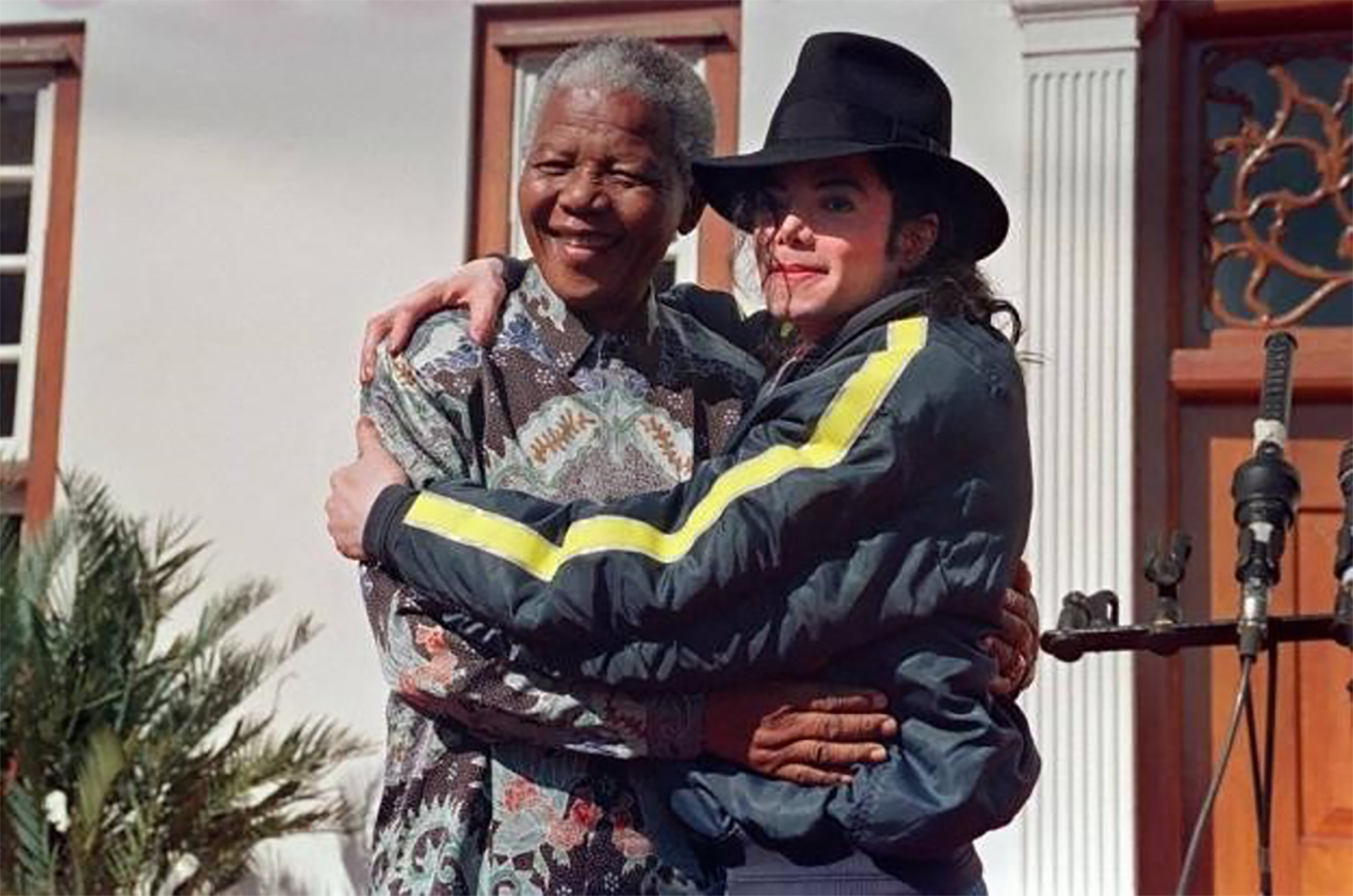

We saw how big the the #blacklivesmatter movement was, not only African Americans, but also in places like South Africa or the UK thus implicating a larger Afro-diasporic community and continental African people.

If African American people want to exclusively use the term Black to describe themselves, how does that change the synonymous group of language that has been assumed with the term for decades now, and where does it leave the rest of us?

Although the intention might come from a historical notion and a historical sort of integrity and world of inventions — such as African Americans developing their own sense of culture as a group during times of struggle and liberation — there is an ambiguity in the term “Black”.

Ultimately, the likelihood of it being exclusive to just one nation group seems to be low, as the word has made its own mark in different lands with different meanings.

When the conversation about reclaiming a Black identity to African Americans exclusively comes up, one must remember that in this current time, Black has evolved and stretched itself to mean and include multiple things which creates circumstances where the conversation of reclamation becomes a bit redundant and the bigger issue becomes about what structures within white supremacy, historically and currently are leading us to have these urges and have these conversations.