In less than a month, Miss SA, as an organisation at large, has once again shown us why it and pageants of a similar nature are not to be trusted, nor accommodated in 2021.

Since Lalela Mswane‘s crowning as Miss SA 2021, the organisation has exhumed decades worth of its own racist, segregationist history.

In the last week, there has been rising pressure from South Africans to have Mswane boycott the Miss Universe competition which will be taking place this December in Israel. This is related to Israel’s ongoing and historically unfaltering Apartheid politics, oppressing the people of Palestine.

For Miss Universe Organisation (MUO) — which in its own words “celebrates women of all cultures and backgrounds and empowers them” — to host the pageant within an occupied country which actively derails and ruins the lives of so many femmes is hypocritical, at best.

Unfortunately, it is also of no surprise seeing as MUO is based in the USA, which annually funds billions into Israel (largely for military aid, no less).

Yet the real salt in the wound is for Miss SA to be taking part in this, in spite of pressure to pull out. With Miss SA representing a country which is still healing from the deep wounds of our own Apartheid past and legacies, it is understandably infuriating that we would send our own to another state that perpetuates Apartheid.

One would think familiarity bears with it some lessons learnt. If so, one of those lessons would be that the world can, even through pageants, make necessary political stances.

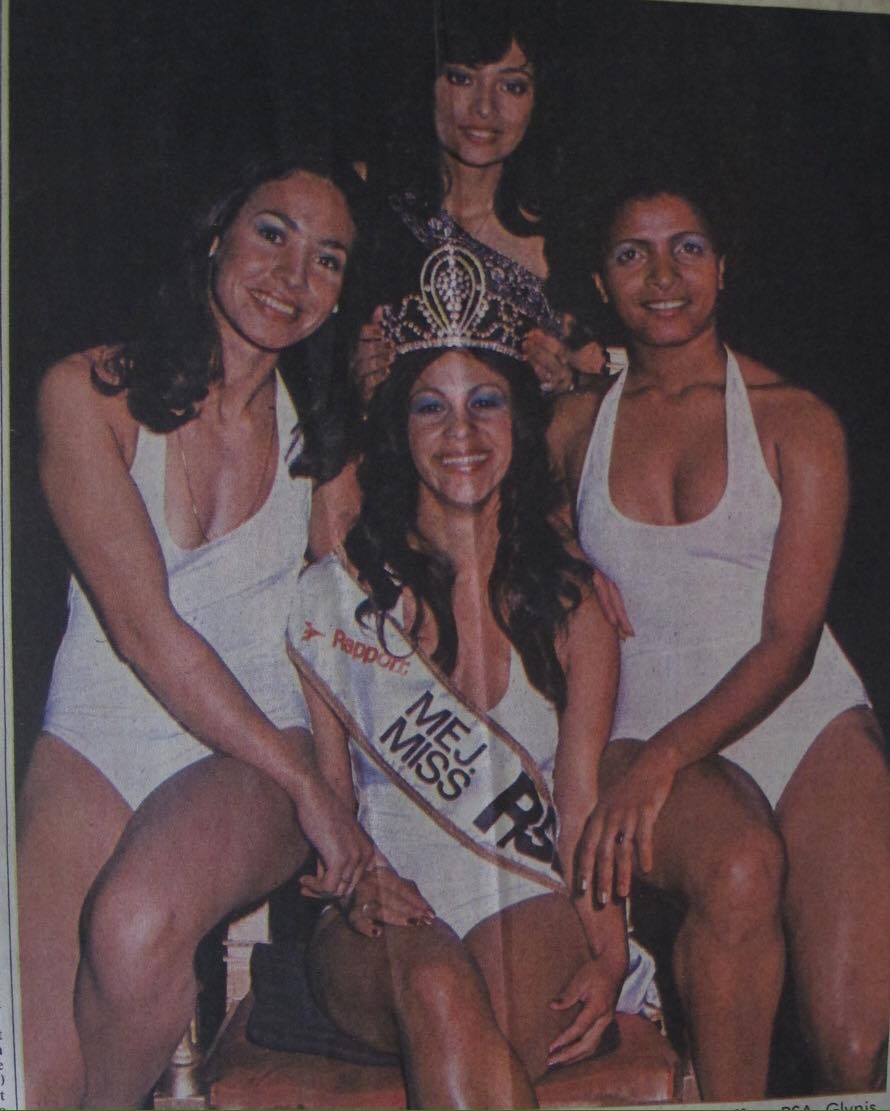

In the late 1970s, the Miss Universe Organisation sanctioned any South African participation. Then, South Africa would send two candidates to compete for the crown; a Miss SA, who was white, and a Miss Africa South (AS), who would be Black or of colour.

The MUO’s motivations, although unwritten, were very likely mirroring those of many other institutions across the globe which were saying no to South Africa’s Apartheid policies and politics. For Miss SA to release a statement this week that said that MUO is “not a politically inspired event” is both ahistorical and almost works as an attempt to gaslight a whole nation.

It simply isn’t true. It isn’t true that Miss SA itself isn’t political either. It can’t — regardless of its words and intentions — separate itself from the politics of beauty and the game it’s playing in states competing in subtle ways for power and recognition. Games which won’t end.

It is this relentless quality — which I have previously spoken about in an article posted earlier this month, that is deeply concerning to me. The line is never drawn in this pursuit for ascension.

In response to the calls for withdrawal from the Miss Universe competition, the official Miss SA statement attempts to guilt trip the reader by letting them know that this has been Miss SA’s childhood dream.

They bring up Mswane’s previous experiences with bullying as a child, seemingly saying that public pressure to withdraw from the competition isn’t too far off from that bullying.

For the organisation to go as far as to manipulate the narrative in this fashion is frightening. We are to accept and believe that Mswane’s childhood dream surpasses the need to hold accountable the “state” that is responsible for ruining the dreams of so many other children. All of this for a crown and an organisation’s profit.

Yet, in the same breath, the Miss SA — and Miss USA, for that matter — will offer stances that seem progressive and “inclusive” like opening the competition up for transwomen.

Had the pressure mounted enough, with enough people and across more traditional media, I assume Miss SA’s initial response might have panned out differently. What this highlights again, is that Miss SA’s purpose in today’s society always seems to be taking a stance after much public pressure, and then only to a certain extent. Otherwise, the organisation is set in its ways and even more set on getting the next big crown, at any expense.

If Miss SA — as it claims — is our leadership for a generation of younger femmes, I fear the direction in which they would be led if they were to follow in this organisation’s footsteps. These footsteps which seem to not care much for where they tread, as a greedy culture of acquisition leads them right into another Apartheid state’s town.