On the violence that continued;

“On June 17, I watched as bodies were dragged out of what had been a shopping centre on the Old Patch Road. I saw figures running out of the shop, some carrying goods. They ran across the veld like wild animals, dropping like bags as bullets hit them. I saw billows of smoke shoot up as the white vehicles burned. I thought the world had come to an end. I saw leaders inside and outside Soweto plead for reason and I saw people detained and killed.”

Nomavende Mathiane, journalist

Source: Bonner, b & Segal, l (1998) Soweto: A History

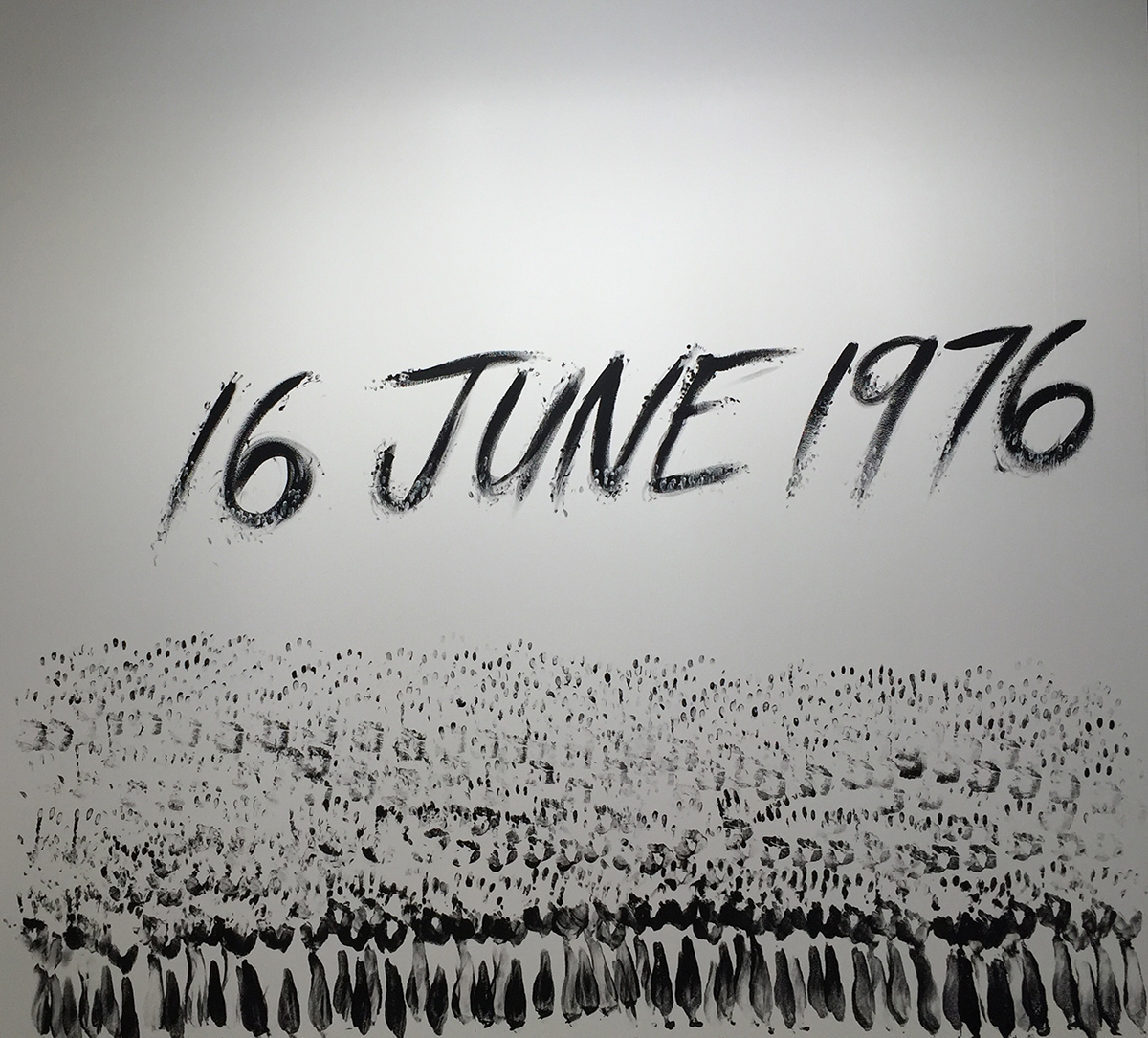

June 1976 South Africa.

I looked over my shoulder, looking to see that no one was following or watching me as I crossed the gravel road to my church. A few members of the Anti-government Freedom party had held a meeting in it one day and during one of the raids, a group of police had been particularly evil. They locked the entrance and set it alight, ignoring the innocent screams of women, and the helpless shouts of the men contained inside. The men’s helpless deep grunts slowly died away as the inside of the church continued to be consumed by flames. By the time the police had left and the overworked firemen put out the fire it was too late. The bodies were burnt beyond recognition and only the outside of the church had remained almost unburnt. I lost my mother that day, I remember rushing to try to find her, screaming out “Mama! Mama Ukuphi? Where are you?” When I finally stumbled upon the only body with a golden locket around her neck, a gift from my father, I knew it was her. I remember screaming until my lungs hurt and my eyes watered. The Bishop tried to pry me away from her body but I held on, afraid that if I let go it would make the nightmare a reality. I lay next to her and sang the lullaby she sang to me on sleepless nights, “Ubuthongo, Unkulunkulu uyokuvikela, ngiyakuthanda ngane yami, phumula, lala ngane yami.” Sleep Mama, God will protect you, I love you, mama, rest. Sleep, my mama.

Losing her had destroyed my soul and for months I wandered around aimlessly like a ghost without a purpose. She had been so hell-bent on fighting for freedom, for liberation, and now she was gone. At night when she had tucked me in, she would tell me that every time she fought she did it for my brother and me. Now as I looked up at the sky I hoped she was looking down on me from heaven; Mama ngikukhumbule I miss you. I shook away the unwanted memory and swallowed the lump that had gathered in my throat. I pushed at the wide doors of the church, and finally, with a low creak they gave way. The pew where countless of us had been baptised was now covered in black soot, the wooden rows of benches had fed the fire and what was once a beautiful place of worship was now a black scar caused by the injustices of the Apartheid system. The only thing that remained unscathed was the statue of Jesus, he continued to hang from the cross looking over the ruin with a pained expression. As I looked around my burnt church, I held fond memories of Sunday praise sessions and the Bishop’s fervent prayer for the end of segregation, I had wanted to have as much faith as he did, but I, like Mama, believe that God helps those that help themselves.

I walked through the ash and made my way to the stairs that led to the church crypt. There had been a time I was afraid of the darkness that led down into the heart of the church, my brother had always teased me and said that when the Bishop cast demons out, they were sentenced to an eternity in the crypt. The thought of my brother’s childhood spook stories and constant teasing brought a smile to my face. Ever since Mama died he had taken on the role of the autocratic parent rather than a brother, and now he was also part of Them, my heart ached and I willed away thoughts of him.

I reached the bottom of the stairs and thought about how this had gone from an imagined demon prison to my sanctuary. There in the middle of the dust-filled crypt under the light of a single candle was my heart in the form of a person, Daniel. I inhaled deeply at the sight of him, tall and hard from the days spent in training camps. His youth had been taken away by the evils of conscription into the townships and even when he said he would rather serve prison time, his father had sjambokked him into submission and told him it was his duty to get rid of the communist kaffirs that wanted to steal South Africa from them.

Yet his beautiful face marked only by a thin red scar remained angelic but still held the uncertainties of a teenage boy. His black hair tumbled down into his face as his startling blue eyes drank me in from head to toe, reminding me of the countless times I had been enwrapped in his arms. His lips curved into the smile that made my heart flutter and my knees weak. When it was Daniel and me, I could forget that he was white and I was “non-white”, I could forget that there were laws, specifically the Immorality Act that forbade our being together. Here in the heart of the church where my mother had breathed her last breaths, I could be a 17-year-old girl in love with a 19-year-old boy.

I jumped right into business before he could distract me; “I have something to tell you” I said,

“Do we no longer go through the pleasantries of greeting each other?”, Daniel answered.

“Pleasantries? What does that mean?” The inferior system of Bantu education had left a gap in my knowledge and big words and their meanings often puzzled me and left me feeling confused and stupid. Daniel often brought books to our secret meetings, he would sound out the words for me and tell me their meanings, it was because of him that I had fallen in love with a language that was not my mother tongue.

“It means…” Daniel started.

“Never mind, it can wait until after this.”

Daniel raised an eyebrow at me in a puzzled expression and moved over to our heap of blankets, he signalled for me to sit next to him. I crossed the room to him and with a deep breath began to tell him the news I had been dreading to tell him all day.

“They want to introduce an Afrikaans medium in the schools, Botha made the announcement earlier this month but we all thought it was a farce. But he means business, Principle Sengwayo made the announcement on Monday. The students have decided to march, on the 16th we will take to the streets and march against this nonsense Botha wants to…” I had tried to say it all in a rush of words without looking into his face, but now turning to look at him I saw his face curve into anger highlighting his scar.

“Thandeka, you cannot put yourself in such a dangerous situation. They will hurt you, look what happened at Sharpville. Do you want to be part of a massacre? How could you even think of being part of something so flippant?” he said angrily.

“How could I Daniel? Because I already receive an indecent education while trying to understand English and now I must struggle to understand the racist language and set myself up for more failure?” I snapped back at him.

Daniel pulled back at my last remark, I quickly realised the harshness of my words. Afrikaans is his language as well and he was anything but racist.

“I did not mean it like that, Dan look.” I breathed in deeply and turned to those eyes that brought me to life, I suddenly remembered how he had saved me. After Mama’s death and the constant violence and hatred in this country, I tried to take my life, Daniel had been walking by when he saw me about to jump off a ledge and talked me down, sometimes I refer to him as my angel. The angel that scared death away.

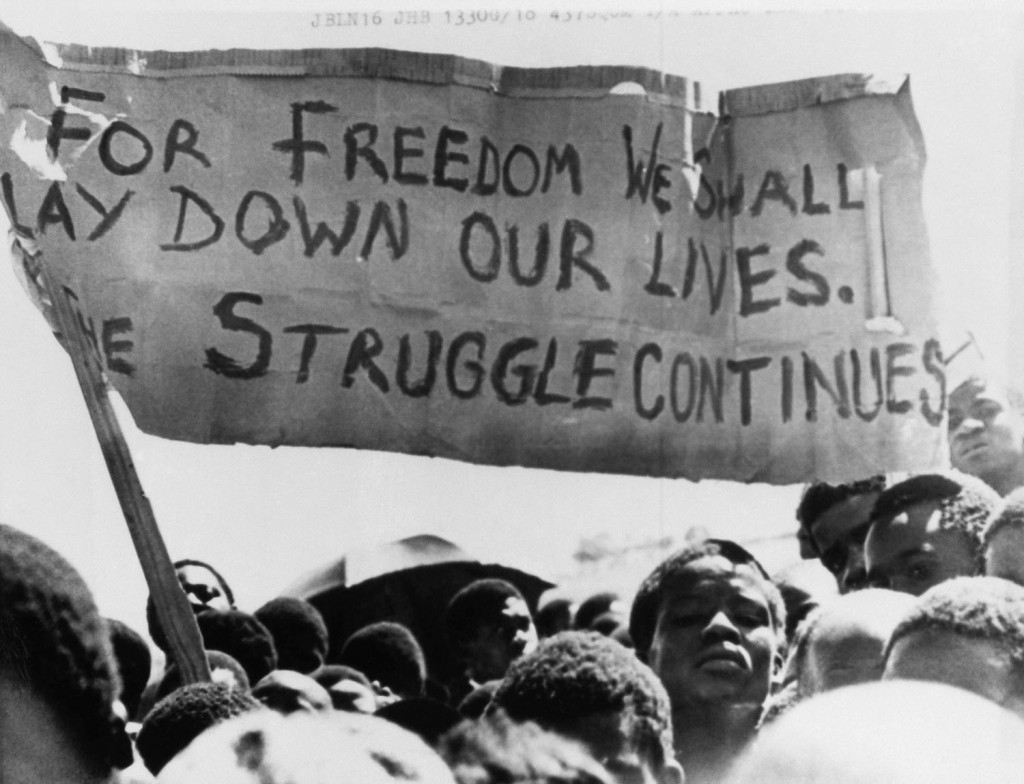

“I want to fight, I see Nomzamo and Lindi, all of them laughing and holding the hands of their boyfriends free in that way but constricted from busses, beaches and sidewalks their fathers get beaten in the middle of the street for not carrying a stupid pass. This march is not just about the Afrikaans, but it’s for freedom. I want to feel free to love you, I want to walk on the same sidewalk as you and not be worried that I will be arrested. I want to fight just like Mama did, not just for us but for our children and their children’s children.” I said quietly.

Daniel’s face softened and he slowly reached to touch my cheek, “I understand, I would like to hold your hand and kiss you silly out there as well. But my love, I like that you are alive and I want it to stay that way for a long time, we need to make these children and see these grandchildren. I know it sounds selfish but here we are safe, they cannot hurt us or stop us from being together in here. Thandeka, I know how ugly Apartheid is believe me. I live with it, my father is hell-bent on destroying anything non-white. You are my hope, when I’m with you I feel alive like God maybe hasn’t forsaken me after all. If you die, I die. I will no longer have anything to live for. The thought of one day being with you, living you with, marrying you — that keeps me going through his abuse, through the training camps. So, please don’t put yourself — my reason on the line,” Daniel said in a pleading voice.

I looked in his pleading eyes and kissed him deeply, his rawness had left me in an emotional spiral. I felt wetness as we kissed and realised that we were both crying, the familiar taste of his lips broke my heart as I thought of how much I truly loved him. I prayed to the Jesus in the church that his words would come to fruition, and that we would get to live in freedom and grow old together.

I made my way home with an aching heart and the memory of Daniel’s pleading eyes. He already knew I had made up my mind about being part of the march. He knew my determination to fight and how the lure of staying at home and letting my friends and people march alone was not an option. As I reached the old rickety green gate of my home, I was suddenly overcome with the worry I once held on the days that Mama was not coming back home. For days on end, she would attend freedom rallies and then come home in a police van after spending a night or two in jail.

There were nights I heard, Jabu willing for her to be more careful and to keep me in mind, still, it had not stopped her. She was a woman on a mission and now she was my martyr. I looked at the house I had grown up in, the small two-roomed pale green house with cracked windows and a butler gate was all I had ever known as home. The small garden was where my brother and I had spent countless afternoons chasing after one another and playing pretend house. The walls held fond memories of my mother’s laughter and warm eyes, her Sunday special yenkomo sikadali beef stew, and steamed bread.

I walked into the house and was met by Jabu’s angry, impatient look.

“How many times have I told you to stop going to that place Thandeka? Does it please you to put your life in danger?” he spat.

“Don’t be stupid Jabu, that used to be our church, I like it there. I feel closer to Mama. The only one who should be worried about endangering their life is you.” I rolled my eyes at him as I tried to make my way past him

“What are you talking about?” Jabu asked incredulously.

“You think I don’t know? You work for Them now, their puppet, running around to collect their rent and make them richer. How do you even look at yourself in the mirror? This is not what Mama wanted. How do you work for the very people that oppress your fellow people?” I said angrily.

Jabu masked the hurt that I had caused him by mentioning our mother but I saw it in his eyes that my words had hurt him. “Thandi, I am the head of this family now, I have to provide for you. I’m not willing to leave you to go to the mines and this is the next best thing. Trust me, I don’t want to be a community councillor but I have no choice.” he said.

His use of my childhood nickname made me long for the brother that was once my best friend and in a silent whisper, I voiced my fears, “If they find out, they will have you necklaced, just like they did to Thomas and Siphokazi. I already lost Mama, I cannot lose you too.”

Jabu inhaled deeply and I knew then, that this too was his fear. “I spoke to Bishop Mokena, and explained why I choose to do it. He says he will ask the community for amnesty, I’m not betraying them, I am just trying to provide for udadewethu omncane.”

His words eased some of my fears and with a replenished smile on my face, I said, “I am not so little anymore, I am as capable of providing for this family as you are. What would you like me to cook tonight Jabulani?”

XXX

I stared up at my ceiling and for the first time felt the nervousness of the events of the day. The march is supposed to be peaceful, but in these violent times, who knows what circumstances might take place. I turned in bed and stared and the sign that Lindi and I had painted when we had decided to be part of the march. In large black letters, we had painted “TO HELL WITH AFRIKAANS”. I wondered if Mama had ever felt this afraid before a rally or if her drive to fight had compelled fear away.

Daniel’s words of wanting to grow old with me and live together in freedom gave me the motivation I needed to get out of bed. I prepared for a day I hoped and prayed would bring change not just for us, but for South Africans everywhere. I dressed in my school uniform, making sure I wore my best tunic, my crisp white shirt and my black polished Toughees. I eyed myself in the mirror, wandering at the girl who looked back; big eyes, bushy eyebrows, short black hair, a skinny pinched body, nothing special. I sometimes wondered what Daniel saw in me, those dark thoughts often clouded my mind, leading me to question if he would be with me at all if Apartheid did not exist…

As I made my way out of the house, sign in hand, I looked over at the large portrait of Mama on the wall, her smiling eyes, the beauty spot on the right side of her face adjacent to her nose, and the perfect all-white smile. She was so beautiful, a strong-willed woman who did everything she put her mind to. Now in the same spirit, I hoped to pick up the torch where she had left it. I looked around the house one last time and walked out.

It was just after 9 am when I arrived at Orlando Stadium and made my way to Jessie’s Hall, I scanned the crowd for Lindi, my best friend. She was standing around with a few classmates. They greeted me with pinched smiles as I made my way towards them. The mood was spirited but turned tense when a boy made his way onto an abandoned tractor to address the already large crowd of gathered students and to my surprise, teachers. In a cool voice he announced, “Bafowethu nodadewethu; brothers and sisters, I appeal to you to keep calm and cool. We have just received word that the police are coming. Don’t taunt them, don’t do anything to them. Be cool and calm. We are not fighting. This is a peaceful meeting and will continue to be. With that said, let us continue on our way”.

The march continued onto Orlando High School. Everyone was merry and signing Zulu songs, appealing to the government to put an end to Afrikaans and Bantu Education. As we reached Verwoerd Street, I heard Them. The police vans all rushed at alarming speeds on the gravel roads, sirens wailing from all directions hurtling towards the march. My heart began to drum violently against my chest, I worried that I would pass out in the middle of the street. Lindi grabbed my arms and gave me a tense worried look, I tried to squeeze back in reassurance but realised my hands we shaking as violently as hers. I silently said a prayer appealing, bargaining to God, asking Him to allow us to make it home tonight.

The vans came to a skidded halt in front of the crowd of students. I recognised Constable Van de Walt. He wore khaki shorts, hiking boots paired with long socks. His face, covered in warts and what looked like a dead rat for a moustache, was set in a hard sneer. The sort of look a person gives just before torturing an animal for fun. He was armed with a hunting rifle. My fear turned cold as more vans pulled up. I turned around and to my horror spotted Daniel climbing out of a van.

He carried no weapons but instead wore his worried expression as he scanned the crowd of protestors; our eyes locked and he gave me a pained expression. Looking into his eyes, I heard the first high-pitched tearing scream. Teargas was launched at us from all directions, chaos breaking out as everyone around me began to run for their lives. From all directions, the crowd began to disperse, but some, mainly the teacher, tried to hold their ground and continued to march on. I heard Gladys, the school choir’s main vocalist belt out a song. She began to heartbreakingly sing “Senzenina? Sono sethu ubumnyama, sono sethu yinyaniso Sibulawayo Mayibuye i Africa” What have we done? Our sin is that we are back, our sin is the truth, they are killing us. Let Africa return.

Eyes turned to her, all in admiration of her vocal talent and awe of the truth of the words she sang. It was amidst the signing, the shouts, the thick layers of teargas and the sounds of Afrikaans men shouting orders that the first gunshot went off. Lindi let go of my hand and run, I stood there too shocked, too afraid to move.

The words from a book Daniel had read to me, Animal Farm, suddenly struck me at that moment, “The creature outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig and from pig to man again, but already it was impossible to say which was which.” I did not see humans when I looked at the sneering and laughing policemen, but instead, pigs who did not carry one ounce of humanity.

I was brought out of my head when I felt a tight hand tightly wrap itself around my arm and begin to pull away. Looking up, I saw that it was Daniel. I turned my head when I heard a high-pitched scream coming from a young girl who ran alongside an older boy carrying a bleeding and dying boy. So much blood ran from his body, I knew that by the time they reached a hospital, he would be long gone. I tried to pry my arm away from Daniel, knowing that he was risking his life by simply touching me. I tried to speak, to sound out his name but my tongue lay slack in my mouth as fear crippled my ability to speak. I felt as though I was caught in a nightmare. Everything that was happening seemed like a distant nightmare that my mind failed to grasp. Daniel began to run pulling me behind him, bullets buzzed above our heads and teargas clouded our vision. More and more screams filled the air as stray bullets found the flesh of their targets. Suddenly Daniel came to a stop, “Thandeka, Thandeka you need to run, go home. This is as far as I can go without raising suspicion. Love, please look at me, please please run.” His strained yet urgent and desperate voice brought me back from the daze. I looked into his eyes with gratitude as he let go of my arm and I began to run for my life.

It’s a strange thing being shot. The bullet enters your body at a hyper speed and you don’t really feel it. What you feel is the explosive pain afterwards, the feeling of all your nerves and muscles being torn into. The hole left by the bullet, acting as a tap that allows the blood to escape and pour itself onto the dirty gravel. I fell suddenly, not having the opportunity to brace myself before I met the ground and the pain took over. I gently touched my leg, surprised when my hand came away red. I smiled inwardly as I thought of how my mother’s blood had burnt out in a church and now mine would spill on the streets of Soweto. I tried to hoist myself up but failed when the pain threatened to swallow me whole.

“Thandeka!” Daneil’s distressed voice called out my name. His face bared so much pain, I wondered if he has also been shot. He began to run towards me, I wanted to scream at him to stay back. It was too dangerous. My vision began to be clouded with dark spots as more blood flowed from my leg. Of all the ways to die, this would be it. Daniel continued to push his way through people, I watched his body move with appreciation. His face and beautiful body were not a bad sight to witness before one’s death. Finally, he reached me and crouched beside me, slowly assessing the damage to my leg. I reached my hand out to touch his face for the last time. His cheeks were wet with tears and I wished that I was strong enough to lift myself up to kiss them up. “Hold on Sweetheart, this is not how you die okay? You can’t leave me alone. Remember what I said about growing old together? I love you Thandi, please love. Hold on for me.” Daniel’s voice came out choked and shaky. He took off his shirt and tied it around my wounded leg. I wanted to tell him it was okay, I was okay with dying, that I would be with Mama and I would tell her all about him.

Suddenly behind Daniel, a man cast his shadow over us blocking out the sun. Daniel slowly stood up as if he expected this. “Daniel wat doen jy? Is jy mal, los die bloody kaffirs!” My broken Afrikaans understood this to be a chastising. I looked up at the red-faced man, when I studied his face and landed at his blue eyes I knew I was looking at Daniel’s father. Daniel turned from his father, with words I caught only the end of. He loved me and no one would stand in his way of saving my life. He pressed his warm lips to my forehead and gently picked me up. I looked at him and then at the shocked face of his father and then at the chaos that surrounded us. It was amidst the blood, the chaos and the stench of death that I thought that perhaps happily ever afters only happen in fairytales.