Discourse around fashion is constantly in a game of back-and-forth, with new problems arising at every solution. For this reason, it’s hard to keep track of where it is the industry stands on many matters.

Vogue Magazine as an empire — has acted as a relatively good marker gauging industry attitudes reflected on a large scale – at least, within a Western context.

This specific context tends to be faced with criticisms of exclusivity in representation – in everything from race to gender-presentation. To this day Africa still lacks representation, even through a single country, in the franchise.

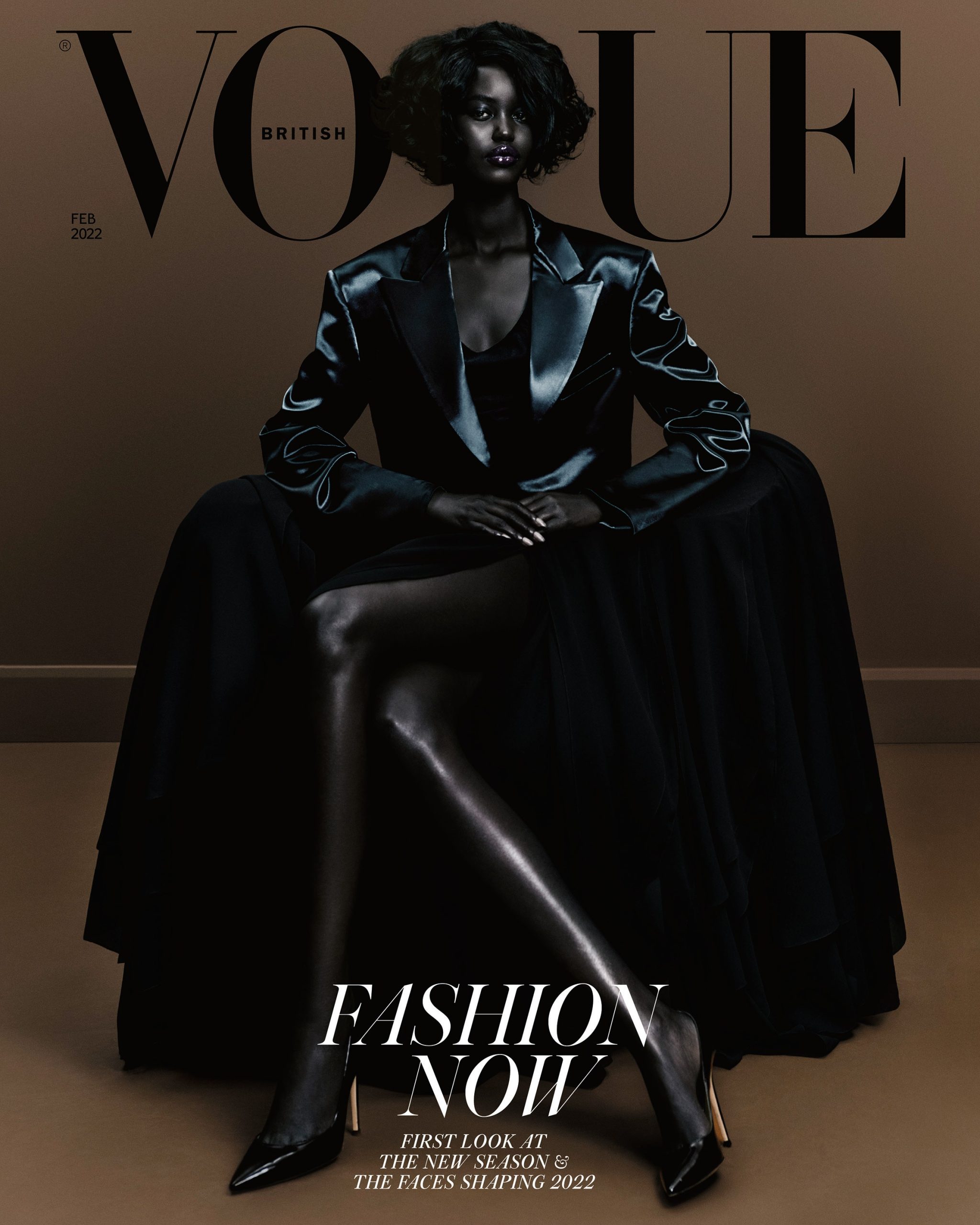

So, it was quite the shock when none other than British Vogue made their February cover in tribute to the changing industry, honouring “the rise of the African model”.

The February cover goes on to feature many models of African descent — including global forces Adut Akech and Anok Yai — amongst other rising models from across the continent.

In theory, I think that the creative direction and thesis for the cover deserves some applause for serving as an example of representation and inclusion. Representation is a practice, and requires actual work.

However, the execution of the cover generated lot of controversy and deservedly so. Much of the controversy surrounds the tones of the photograph, both the atmospheric tone, and the actual skin tone of the featured models.

The styling of the models in black formalwear, coupled with their serious gaze into the camera, generated controversy around the representation of Africa — seemingly at large —through their sombre expressions.

More so, the criticism was specifically focused on the darkness of the models’ skin tones. Photos of the models from their social media and other sources outside of the shoot show that they are several tones lighter than depicted on the cover therefore, denoting that the models had been edited to an almost black complexion.

South Sudanese comedian, Akau Jambo, remarked that he had never in his life seen anyone who looked the way the models had been represented, proceeding to call it “Black Skin Porn. Black Fetish. Reverse Bleaching.”

Amongst a sea of critiques on both the official British Vogue’s Instagram post and others, the term Reverse Bleaching particularly stood out for me — really pointing to the back-and-forth nature of discourse.

For years, we have fought to see delicate representations of dark skin femmes in the media, captured in all of their beautiful Blackness.

As opposed to simply doing that, dark skin has been taken, exaggerated and now used as the almost black flag in virtue signalling efforts.

The practice of lightening Black models’ skin for the purpose of upholding a specific beauty standard — in this case — has truly been reversed, altering the very same Black skin to establish a new, mystified image of beauty.

Of course, this isn’t to say that the models themselves aren’t beautiful and deserving of being on the cover.

Many remarked at how exciting it is to see so many dark skin femme models together, but to shoot the photo in such low lighting that essentially erases the diversity in skin tones, makes the project counter-productive. It perpetuates the image of Africa as a monolith; one skin tone, one people.

The sentiment behind the photos, as shared by first ever Black British Vogue editor, Edward Enninful, was to counter the trend of high fashion brands using one or two dark skin models and considering their work done.

While that is by no means better than what was captured on British Vogue, the issue here is that Africa remains a resource of fantasy and mystification — now with the darker skinned model as “the better accessory.”

While representation is indeed a practice — when conducted incorrectly — it works to reduce the term to a buzz word, which does nothing to help anyone.

What’s more, in the fashion industry – where image is everything – buzz words like representation influence the images that grace the cover of the biggest fashion magazines.