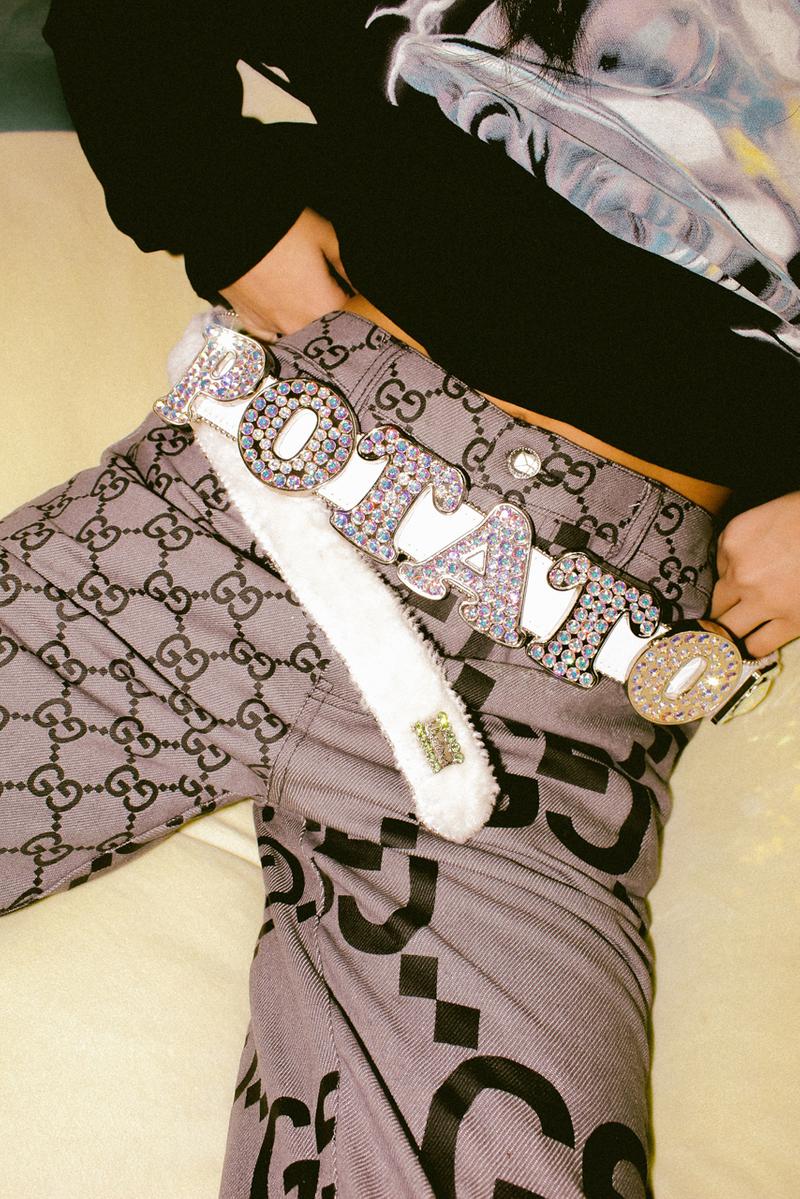

Imran Moosvi, better known as Imran Potato, is a creative who I can only begin to describe as a Millennial Dapper Dan. However, unlike Dapper Dan, the media in which Imran creates his bootleg creations with/on transcends just clothing. Moosvi gained traction due to his bootleg designs which, like Dapper Dan, borrowed the iconographies of famous designer brands. I think what draws me the most to his designs is the nostalgia I felt upon first seeing them and being taken back to being a young brown femme going to the Fordsburg Square — a marketplace filled with knockoff items — and seeing familiar designer monograms on everything from tracksuits to kitchen appliances. In an interview, Moosvi admits that his brand’s identity is driven by the knockoffs he saw his immigrant parents bring back from their home countries, which have a massive market for counterfeit designer products. I can only imagine the things Moosvi saw his parents bring back as being similar, if not the same, as the things I encountered on trips to Fordsburg growing up. Imran recalls, “I would see my mom, who is Iranian-Indian, wearing these knockoff Louis Vuitton and Gucci hijabs that my naani (grandmother) would buy for her,” continuing “It was insane because I would hear about these brands in my music and sports culture, and she’d be wearing the same stuff, but in a very unique and different way.”

Imran’s creations now range outside of just knockoff clothing and include items such as Gucci baby dolls and shoes which resemble hyper-realistic feet. While absurd, you can’t deny how visually striking his creations are. To me, they appear almost reminiscent of my days on Tumblr seeing the monograms of high fashion being applied to mundane objects. While through this description it is easy to believe that Imran’s work appears kitsch, however, I believe his unique designs rather marry high fashion and pop culture, creating their own visual language that will stand as a testament to the times in years to come. Looking through his website alone one gets the sense of the early internet aesthetic that is prevalent in his newer designs. The website feels as if it had to be accessed through dial-up internet, while scrolling I could imagine an array of sound screeching to allow me access to the site. “I don’t take myself all that seriously and that translates in my clothes.” Relays Moosvi, as one can tell his designs are both satirical and fashionable.

Moosvi’s knockoff clothing designs allude to the elitism that comes with being a celebrity concerning their relationships with designer apparel. It appears almost strange to me that younger celebrities are opting for custom, bootleg designer-adjacent apparel when they have the means to buy out entire designer collections. Perhaps, through relying on iconic monograms Moosvi’s designs allow a better job of portraying the aesthetic of wealth than a simple designer item which rather includes monograms in a more subtle form. This suggests that the aesthetic of wealth and access cannot be bought through money, and the luxury of affording high-end apparel, but rather through status. Moosvi does not sell his custom designs seen on celebrities such as Billie Eilish and Travis Scott but rather gives them to celebrities free of charge, it is not the monetary value that determines the worth of his creations but rather their exclusivity. What Imran’s bootleg work has done is cement himself in with the likes of hype beasts and celebrities who would rather wear a custom design by Imran than a haute couture designer item, and established his creations as important due to their celebrity approval. If anything, Moosvi’s designs also allow us to question if there is a lack of innovation from the collaboration culture breeding in the world of high fashion. In recent years we have seen multiple collaborations between high fashion brands and streetwear designers/brands, yet these subsequent collections are still lacking the hype and unique aesthetic quality Moosvi achieves in his custom pieces. It also speaks to the potential for an emerging economy that sees for high fashion to meet streetwear in ways outside of the ‘runway approved’ collaborations we are seeing at fashion weeks — a market which at this point is appealing to celebrities exclusively.

However, Imran does not solely focus on bootleg creations. He also creates apparel that aligns with his own brand identity. This is seen in the drops he did throughout the pandemic which saw him transition away from bootleg items and create apparel which he describes as “calmer clothes”. The collection of calmer clothes sees for Moosvi to allude to a Y2K aesthetic with shirts including home phones, DVD players and “Potato Network” logos. The collection was thoughtfully curated and released through a series of images that resemble stock imagery, complete with a watermark. As Vogue points out and to which I agree, the intricacies of the collection are typical of Moosvi’s designs: impromptu and random but yet quite deliberate. The collection is a stepping stone for Moosvi, who has been transitioning away from bootlegs and if it is any indication of where Imran Potato is going in the future, it is a step in the right direction. “I have a lot of cool stuff in the works.” Says Imran who has proved not only to be a moment in celebrity but has also created a creative trajectory that is emerging as only going up from here.