In some cases, the “sub” prefix of a subculture is loaded with layers and layers of history, which saturate it further in meaning. In this case, we take a look at the leather and latex culture of Johannesburg and South Africa at large. Sub, in how the subculture has historically been forced underground; to exist in the shadows of the condemned. Sub, as in the culture’s inseparable ties to domination (and thus submission) and BDSM at large.

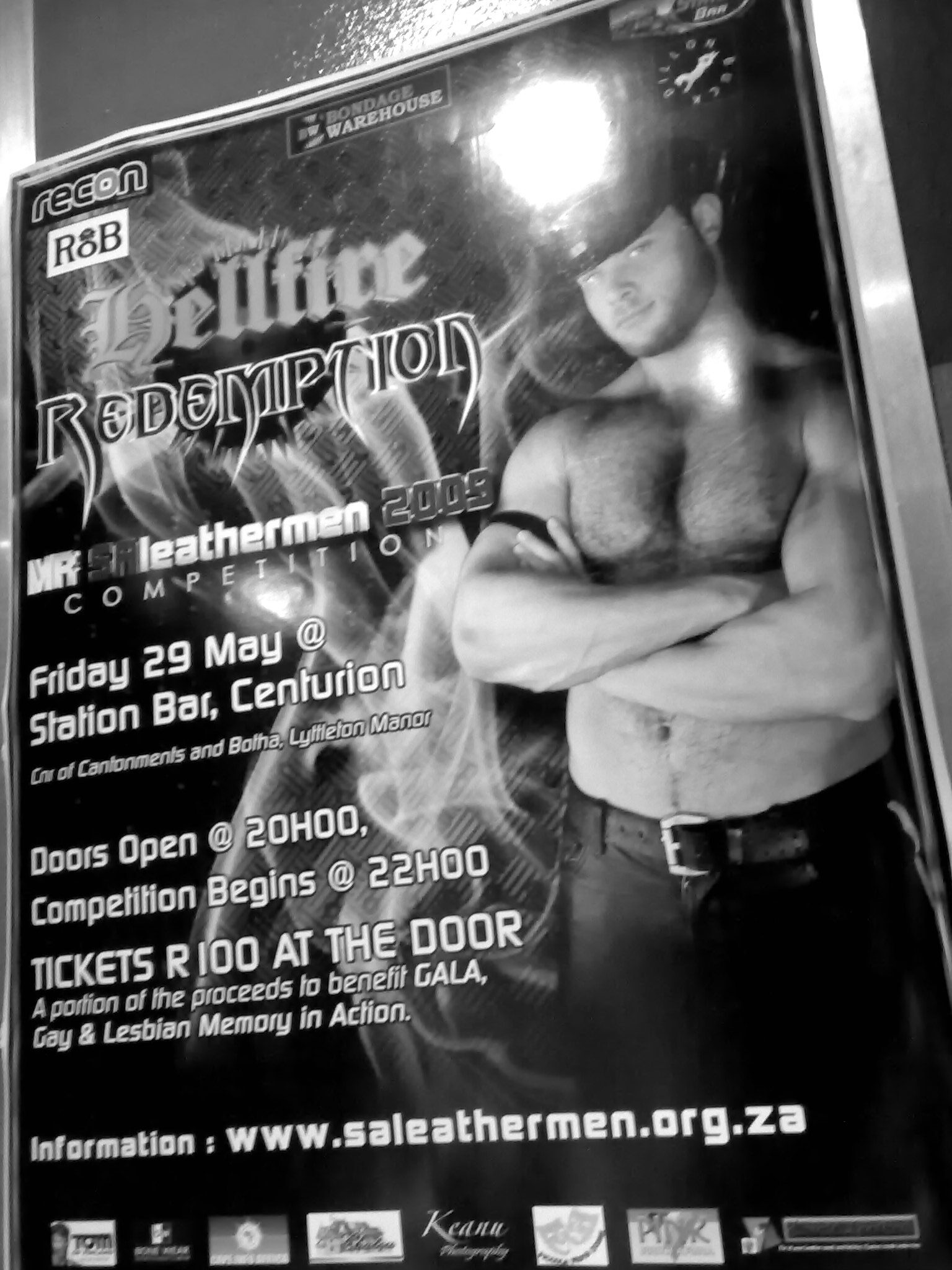

With the subculture having been forced underground in the early 2000s, it’s hard to even imagine what a leather subculture looks like in Johannesburg today. Of course, it still exists, but its roots and originally pioneering participants seem to have been erased from our collective history. But right in the heart of the city, there is memory; a big thank you to the kind staff of Gay and Lesbian Memory Archive (GALA), who offers a rich archive of our so easily forgotten queer history.

Research conducted by Tracey McCormick (2022) finds that the very first local, public trace of leathermen – an(other) archetype within the roster of gay men identifiers—was in an article penned by Lin Sampson for Fair Lady (February 1983), who attended a “gay jamboree” where she said: “One man carries a whip. There is black leather. There is BLACK LEATHER”.

One can understand the shock that warranted Sampson to repeat BLACK LEATHER. This was at a time when the world of fashion (fetishist and otherwise) wasn’t as melded as it is today, somewhat because of policies around the international fashion trade.

However, no one could have predicted the ripple effects of these few words published in an unsuspecting magazine. McCormick details how for months thereafter, a fissure in the queer community was formed, that divided those who were in favour of the association of leathermen with the queer community and those who found it to be morally misaligned and eroticised violence.

The latter camp wasn’t entirely off base; McCormick notes that the US origins of the culture were led by gay soldiers returned from war who wanted to distinguish themselves from the image of the gay man as being inherently effeminate. As such, the aesthetics of leathermen appropriated the imagery of motorcycle gangs, deemed to be unmistakably masculine.

What fascinates me here, as I read these accounts of queer history, both local and international, is how frighteningly similar the internalised homophobic debates of today are. As I paged through the archival pages of Exit – the longest-running South African queer publication, started by the Gay Association of South Africa (GASA) – headlines like “In defence of camp” would appear. In another issue of Exit, adverts for Club Zoo (a self-described “rubber, leather and uniform bar”) would be posted and clearly state “camp queens” had no space in this space.

Club Zoo was just one of a few popular gay leather bars and clubs that popped up in Johannesburg, back when youthful white demographics with a thrill for the city dominated its inner centre. Before Club Zoo came the very first, Batman’s Leather Bar (which evolved from a dark room in a club to its very own establishment). After it came to Jeb’s Leather Bar and Metropolis (which stands today).

When these clubs gained more and more traction, and eventually even made the mainstream television platform SABC, they became subject to “random raids” (for drugs and liquor licenses etc.) from the police. These made the club space feel hostile, with McCormick interviewing club owners who were forced to go underground because they felt unfairly targeted.

Metropolis still exists today, while many of its contemporaries and predecessors do not have the same fortune. I tried to approach another, relatively newer club who have its own leather nights and events to understand how it is that leather continues to live and breathe today. Discovering how too much media exposure historically has worked to only disadvantage these kinds of establishments, understanding can be given to their reluctance to give comment.

But today, while more and more gay clubs across Johannesburg have specialised evenings for leather and are coming out of the shadows, the limelight is shared. While the leather is tied to a culture and history of sexual acts, it is still fashion after all and must be thought of in line with the greater body of fetishwear.

Edenwear Latex champions this front in our local context. The Cape Town-based atelier is true to the heart of couture with its latex specialisation. In speaking with creative director, Simone Delport Dumas much came to light. Firstly, while many make the connection, latex is entirely a different ballgame to leather, albeit existing in the same broader world of fetish.

“Edenwear represents a place where anyone can feel totally most comfortable in your second skin,” Dumas shared. “We are able to provide each customer with a personal and unique experience taking into account the distinctive qualities of each individual and exactly what they are looking for. This is why each latex item or outfit is custom designed and made specifically to size and order taking into account the customers’ needs or interest, making it an experience that is not easily forgotten and holds significance for the person involved.”

This bespoke, couture quality mirrors the individual expressions and desires within the fetish community, as fetish artist, educator and event planner Ms Kitten (fet-world alias) offered. Dumas pointed to Ms Kitten to speak more directly about latex as a culture in South Africa, beyond the design aspect Dumas specialises in.

“Latex can be fashion, an accessory, a kink or a fetish, a total need in sexual experience or it can simply add some sexy into a regular routine. The way the fabric warms instantly and moulds to your body creating an instant transformation opens the door to a different dimension. Touch and sensation over latex are sensory experiences everyone should try once in life,” Ms Kitty shared.

More than what is physically felt and worn, Ms Kitty identifies the most crucial element of all things fetish: the deep respect for consent. “Part of what makes this world so special is it allows us to be heard and gives us a space to hear our partners. Owning ourselves and taking accountability for our actions and sharing our deep dark puddings allows us to share vulnerability with those we love.”

Ruminating on these dark puddings, I think of how far this culture has come. For Dumas and her over 10 years of inspired Edenwear, inspiration draws as far back as the 1970s when Vivienne Westwood brought latex to the mainstream. Since then, Dumas and McCormick alike acknowledge how leather and latex can even be found on the red carpet these days, lifetimes apart from its typical notorious context.

The thread that runs skin tights over all of these changes is the possibility of fetishwear to mould and change, with inclusivity leading the movement nowadays. Long gone are the days when leather spoke to a desire to be distinguished as a particular kind of man; one who was gay, but definitely not camp or queeny or any other coded misogyny. Now, as Ms Kitty suggests, fetish makes room to listen attentively to the desires of a loved one, in a way that they might not have before. And for those who shamed the hot world of leather and latex into underground circles: things are only gonna get hotter.

Thank you to Linda Chernis (archives co-ordinator at GALA), Simone Dumas and Ms Kitty for opening little worlds to the public.