*This essay forms part of Bubblegum’s Collaboration with Bag Factory and their visiting curator from Uganda, EM Mirembe.

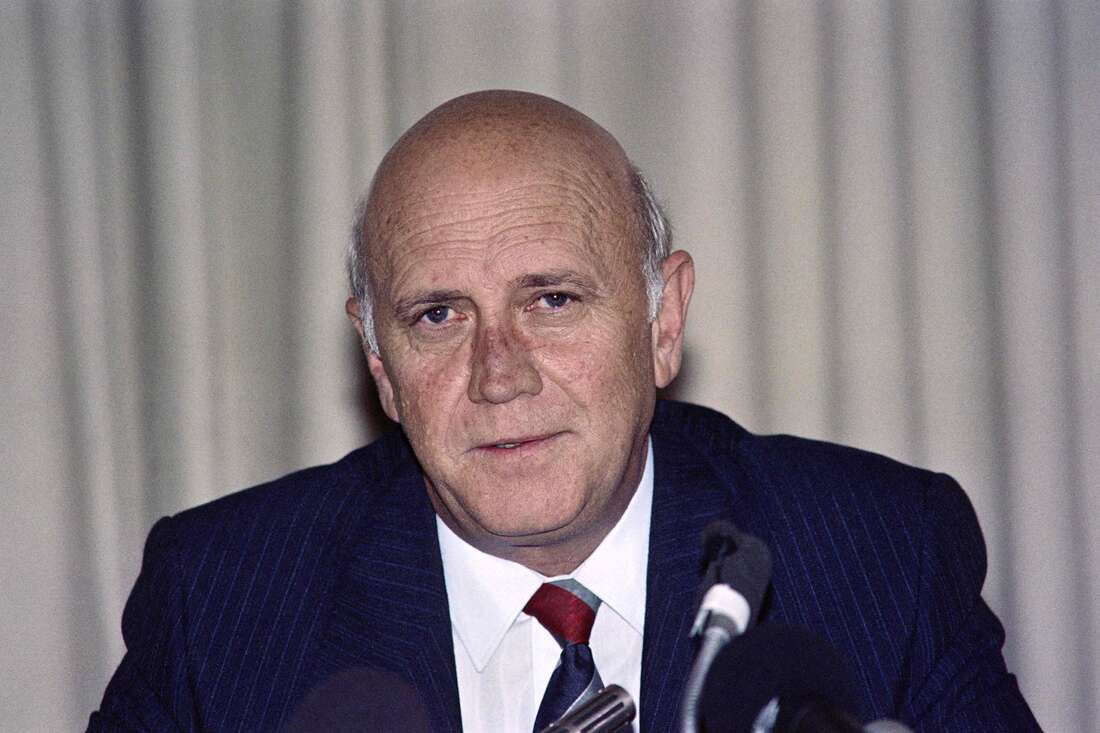

It is the second part of Joburg based art critic and Azanian Philosophical Association member Athi Mongezeleli Joja’s reading of apartheid former president, F.W. de Klerk, pre-recorded “last message” video. Read the first part here.

The metaphor of home instantiates more than just notions of origin, sovereignty or rootedness. It also exudes upon the one, a carefree disposition and the ability to exist truthfully, in freedom.

To say someone is at home, implies contentment and ease within space and time. It is a metonymic portrayal of one’s state of being. We need not to cull from a thousand aphorisms to persuade anyone about what home signifies and what its purchase is in de Klerk’s “last apology”.

But does homelessness then presuppose bondage, unknowability, in-existence and therefore a threat?

Portrait of F.W de Klerk with Maggie Laubser’s painting flanking his left shoulder.

While Blacks are criminalised and dishonoured prior to any transgression, to recuperate their innocence, whites retreat into the banalities of human existence that is to the prevalent perceptions of whiteness as embodied innocence.

So, not only does racial domination decriminalise itself by criminalising its victims — as Steve Martinot brilliantly observed — but that whiteness also humanises itself through the relational matrix that avail Black flesh as putty made and remade from the multiples images, anecdotes and types inscribed in the colonial archive.

Frantz Fanon invokes this parasitic discrepancy when he writes: “The presence of the Negroes beside the whites is in a way an insurance policy on humanness. When the whites feel that they have become too mechanised, they turn to the men of colour and ask them for a little human sustenance.”

Building on Fanon’s trajectory on the aporias of post-colonial expressive cultures, scholars have observed how blackness remains a national malediction in the post-apartheid visual art practice.

Despite the articulated fantasies befitting a “new” national sensibility —“simunye: we are one!” —the African body repeatedly re-emerges in both visual and public culture as a displaced oddity, a bestiary fascination that is strangely laden with all kinds of contradictory signifying properties.

What then does the presence of a Black woman’s portrait do in de Klerk’s video? Who is she? Who painted the portrait? What political, libidinal and economic currency is her face and flesh bringing in the visual narrative?

Is her prominence and participation in the frame that of a symbolic cannon fodder for white self-reinvention?

Not knowing, myself who she was and/or who had painted the picture — despite my own expertise as an art critic with vested interests in South African modern expressions — I turned to friends and colleagues in the field of visual arts who then attributed the work to Maggie Laubser (1886-1973).

Generally, the picture resembled an approach to genre painting influenced by prevalent early 20th century European styles and movements, which combined modernist expressive distortions with local primitivistic predilections.

In the case of Laubser, her painting forms part of a series of simplistic, child-like portraits of native women in head scarfs, particularly yellow scarfs, rendered in non-naturalistic colour hues. Judging by recurrence, Laubser was fascinated by the colour yellow as she was also intrigued by the exotic beauty of natives and other locals of colour.

Dorothy Kay, Black cook Annie Mavata; nd.

In this painting, title currently unknown to me, the arguably young dark-skinned woman servant is dressed in brightly coloured clothes — interestingly whose palette, a friend alerted me — resembled those of the ANC.

Unlike some of her colleagues who identified their native subjects by what David Koloane described as “objects with labels” illustrating function, Laubser’s portraits often identified her subjects as familiar — aunty this, grandma that — usually in Afrikaans.

But if colonial recognition of the humanity of the oppressed did not redress racial subjugation but tended to mask it, exceptionalising Laubser’s little gestures emboldens her paternalism.

In an ominous pose, Laubser’s subject holds with her right-hand side some flowers (daisies perhaps) thrust to her bosom as if pledging allegiance or demonstrating conformity.

Portrait of F.W de Klerk and Nelson Mandela.

The push and pull dynamic between her body and everything else around her, exaggerates her subservience. Despite their seeming unavoidability, her brightly lit eyes show no emotions as they stare beyond their viewer.

After all, the master/servant dynamic, which colonial ethnographic portraiture hardly disrupts by representing the native, forbids subordinate looking their racial superiors directly in the eye.

Laubser grew up in the farms outside of Cape Town, so some of her painterly subjects — alongside the expressive landscapes and still lives — either “belonged” to her family, or to her friends and other whites.

Besides the aesthetic interestedness in the perceived simplicity and purity in non-western cultures or as it would later be, the copying of their “primitive art” — the appeal of genre painting as modern enterprise in the “new worlds,” was as a political, pedagogical and heuristic intervention.

Portrait of F.W de Klerk taken in Pretoria, November 09, 1989.

Artistic representations offered a visual experience to the nascent discourse of the colonial ethnography of non-western peoples, particularly those in the so-called global south.

Notions of modern versus tradition, civilised versus primitive, culture versus nature, white versus Black etc. all heightened and universalised racist narratives that became essential for the development of modern sciences.

Images of the docile, tribal and helpless native, were not only romanticised in these discursive regimes, they also functioned as testaments of imperial benevolence and evidence of conquest.

This coterminous expression of fascination and revulsion that developed in Western modernity and modernism, articulated a generalised colonial structure of feeling. The indispensability of the encounter and repeated assault of the colonial other helped suture the much-ravaged psychosocial bonds of western subjectivity.

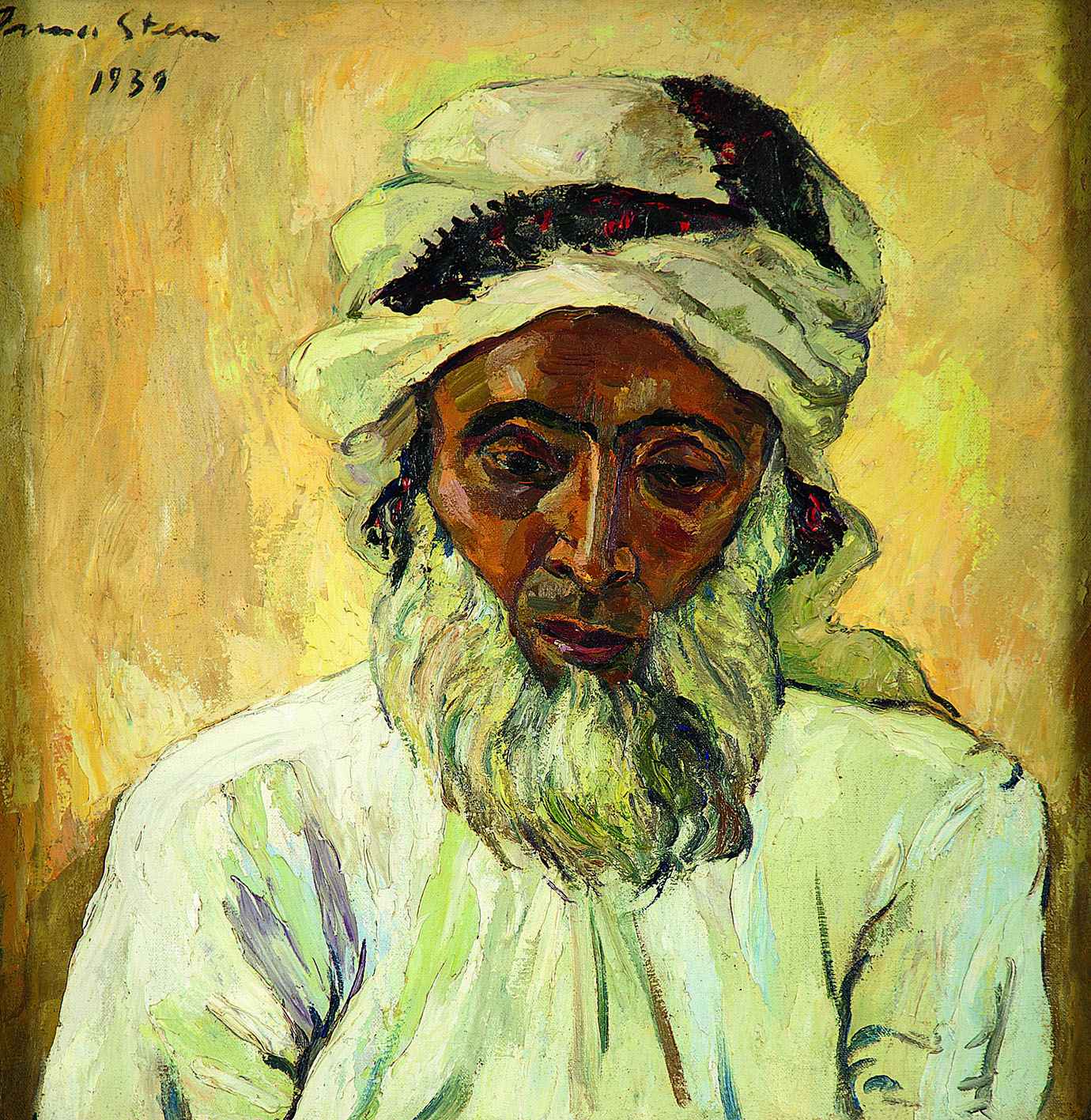

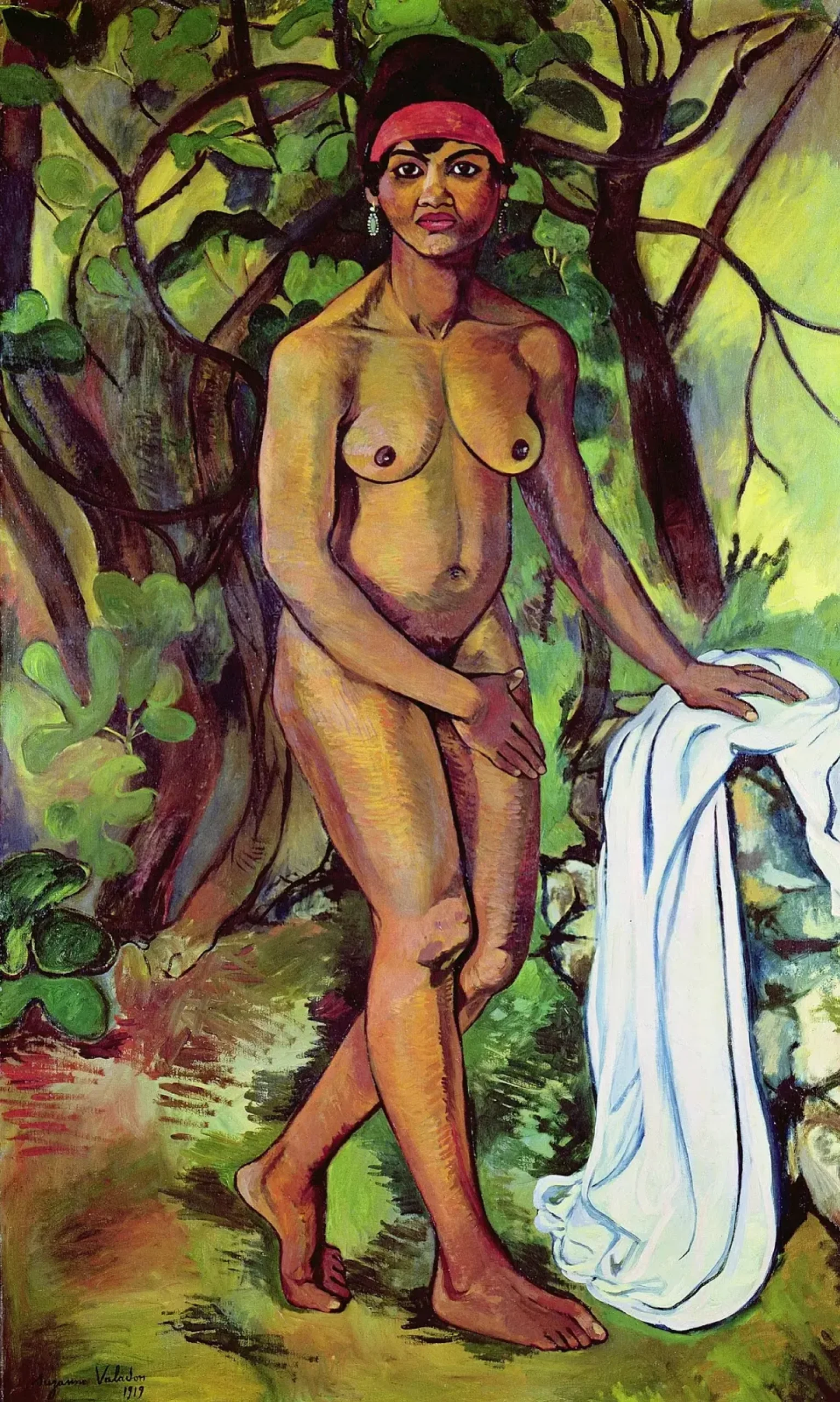

Irma Stern, Watussi Woman; 1946.

As part of settler-colonial community, artists like Laubser, Irma Stern, Dorothy Kay et al. not only shared this exoticist fascination and exploitative conduct with the rest of a rapidly “modernising” colonial project, but adopted its mechanism in their works.

Within the same political system of dispossession, visual arts occupied a different but similar role to the one played by the maxim gun and the bible.

Critical art histories have not only decoded and lampooned the visual cues and modalities of representation typical and acquiescent to colonial sensibilities.

Predicated in the study of power, particularly how image-making processes in historical and contemporary context distribute and reproduce power, critical scholarship has also been privy to various approaches that smuggle or are circumscribed by these tendencies in global visual cultures.

Maggie Laubser, Basutoland Hills; nd.

For example, in one of his early reflections on Kay’s portrait of a Black cook, Annie Mavata, Koloane pays attention not just on the pictorial depiction but also — for a lack of a better word —the extra-pictorial dynamics between the artist and the native seater, was that the “contact there…is regrettably through the master/servant relationship.”

Rendered with aesthetic exactitude, as she looks directly at the viewer with “marginalised eyes that stare back without judgment” in the words of T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting, Koloane refuses to accept that this venerative gesture of Mavata disappears the established hierarchy as the “artist employer can often become an obligation on the servant’s part.”

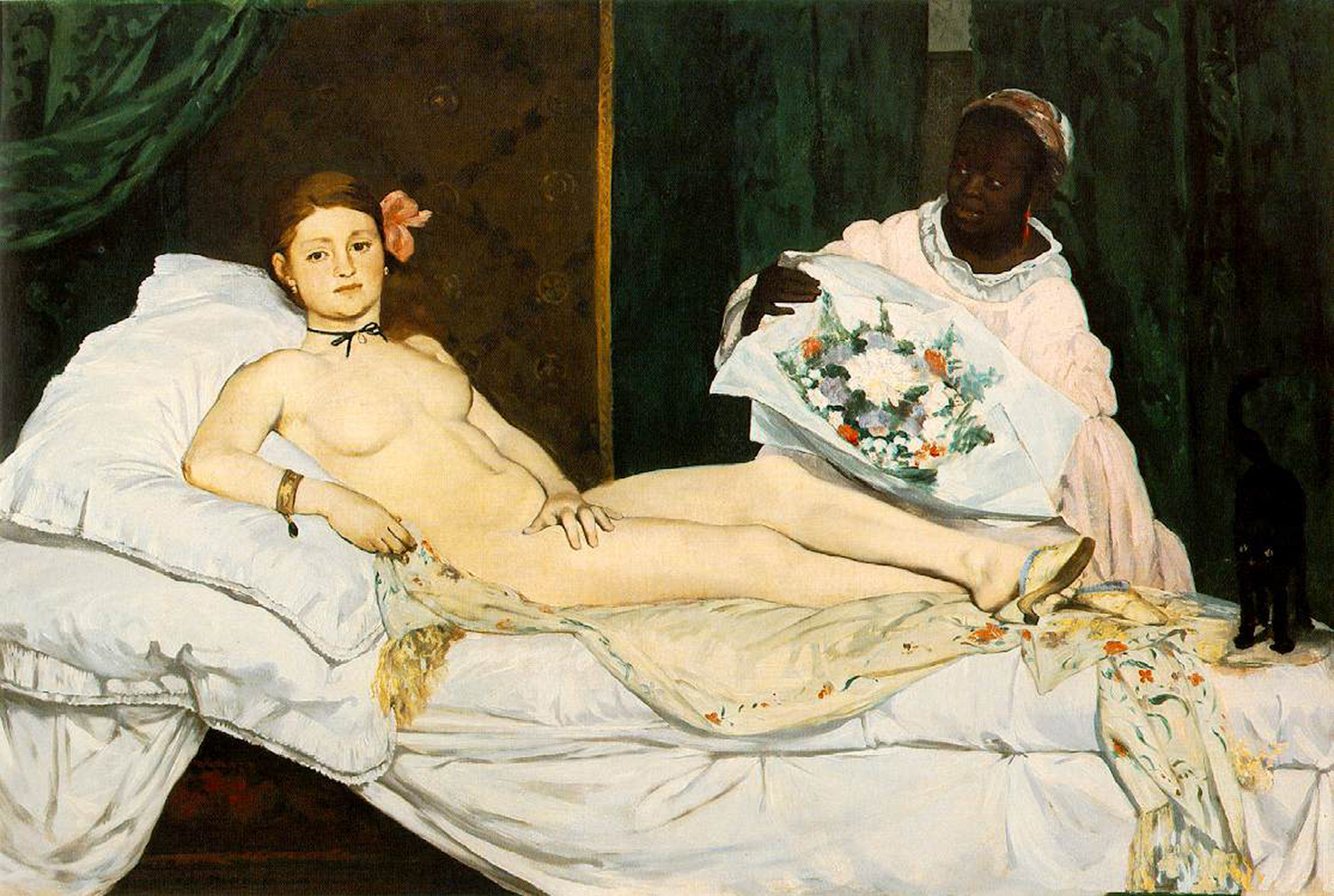

In the work of Simon Gikandi titled Slavery and the Culture of Taste, the presence of the slave in the picture in much of the early European modernist art, announced the both proprietary standing as well as the cultivated palate of the colonial oligarchs.

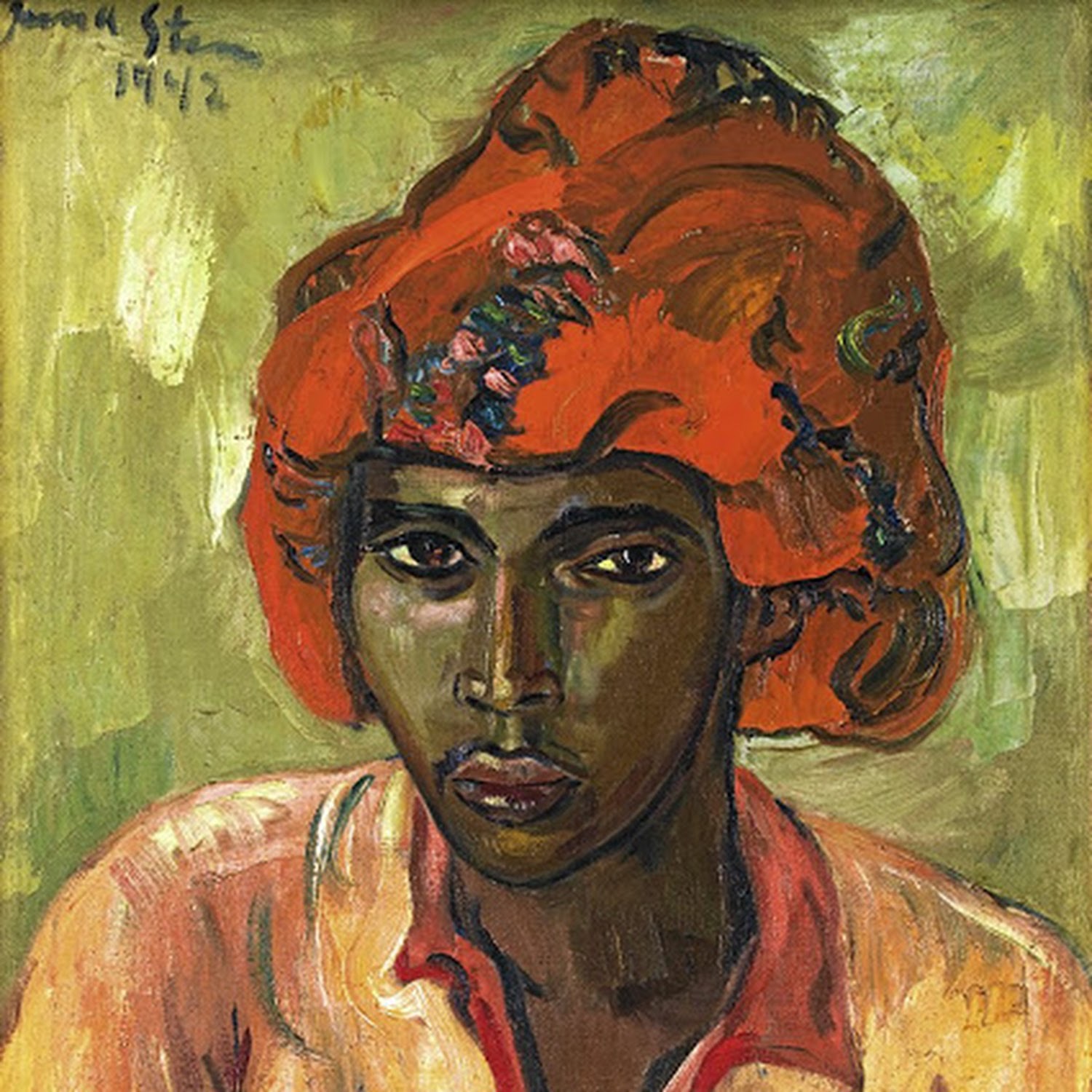

Irma Stern, Arab; 1939.

In other words, painting was a site on which the commissioner brandished his accomplishments, property, and conquests — from horses to slaves — by painterly depictions, as did the slave planter indiscriminately auctioned his stock on the block.

The availability of the Black body as simultaneously dishonoured existence as well as a mark of economic distinction, allowed differently positioned non-black people to objectively relate to the un-sovereign corporeal presence of blackened people as exemplifying unencumbered subservience.

Among the well-to-do commissioners, the presence of the slave in these domestic scenes and even in portraiture and landscapes, signified social status and/or libidinal currency. Blackness here formed part of accumulated commodities. (One of my visual arts informants had let it slip that there’s an old rumour that de Klerk was actually semi-avid collector of South African art.)

Irma Stern, Girl in Print Dress; 1938.

Although the concern with de Klerk’s video-clip relates to choreographic display of a politically staged and suspect contrition — within which the prominence of the native woman in the frame played a significant as well as beguiling role — what I found equally intriguing was the over-familiar compositional and spatial arrangements (the white male protagonist in the foreground surrounded by various domestic and personal items, including the portrait of his native woman) was how it invoked western painterly traditions and the discursive regimes they replicated.

This interstitial cross-reference between reality and fiction, life and art etc. that plays itself out in the narrative scope of the video, speaks to ways in which reality and illusion co-activate each other in the world.

The line that moves from Sara Baartman or Hottentot Venus (actual names are unknown) to Laure (Black figure in Manet’s Olympia) — two figures in western cultural discourse that epitomised what art historian Griselda Pollock describes as “negatively devalued object[s] of a sovereign Other’s refusal” — delineates the longue duree presence of the Black within the racist visual field.

Édouard Manet, Olympia; 1863.

This not only speaks to the raciological presuppositions in western culture and scientific discourse, but particularly how those assumptions undergird art historical thought.

Baartman’s bestialised, exhibited, and ravaged body via western rubrics of racial and sexual difference as the archetype of African bodily freakishness has not just been instrumentalised as the base that helped redefine the metaphysics of beauty and ugliness, innocent and guilt in global imagination.

It has also embodied the corporeal extremity of racial and sexualised savagery that came to comparatively define, describe, and defile anti-erotic corporeality at extreme margins of conservative western standards of beauty and morality.

Laure, however, presents not so much a racial and anti-erotic nexus found in the Black Venus but a temporal and spatial figurative human un-presence in art historical discursive treatments.

One could relate their discordant experiences — one a real person, another pictorial impression of Blackness in Manet’s art — by invoking varying modes of racial invisibilisation in western discourse, in which “blacks, Africa, and blackness are ever-changing boundaries, pliable, makeshift moldings, always in the process of reinvention to suit Eurocentric truths” to quote Sharpely-Whiting again.

One could relate their discordant experiences — one a real person, another pictorial impression of Blackness in Manet’s art — by invoking varying modes of racial invisibilisation in western discourse, in which “blacks, Africa, and blackness are ever-changing boundaries, pliable, makeshift moldings, always in the process of reinvention to suit Eurocentric truths” to quote Sharpely-Whiting again.

While in recent critical theory the racial and sexual relatability and comparability of these figures in the disparate periods of 19th century French culture have been convincingly disputed, I find it slightly difficult to maintain their historically and sociologically specific positions considering that, in the last instance, the reception of both figures in the western visual field represented an absence of human integrity.

The absence or lack of treatment of Laure’s figure in earlier art historical writings on Manet’s works — liberal or leftwing, formalist or socialist — in the words of T.J. Clark shows the “most rueful example of the way the snake of ideology always circles back and strikes at the mind that tries to outflank it.”

Maggie Laubser, Black Swan; nd.

These words of admittance on why the pre-eminent Marxist art historian neglected Laure’s presence in his famous Olympia’s Choice essay, unfortunately did not mark the end of the puritanical approach in dominant art historical methodologies.

If anything, it possibly gave way or emboldened further superficial considerations of Blackness in various modes of articulation in art writing.

In conclusion, with regard to De Klerk’s parting apology, unfortunately unlike in Clark’s situation noted above, there is certainly no one to interrogate regarding, on the one side, the paradox of the critic’s disregard of the hypervisibility of the Black woman’s portrait in the video and on the other side, we are to truly engage what the symbolic value of her fatal presence was in the larger narrative of De Klerk’s last apology.

Irma Stern, Young Arab; nd.

Although many things remain unclear — even at this point regarding the actual intentions in De Klerk’s posthumous video and apology for apartheid — it has nonetheless been “provocative” to say the least.

Provocative in that it has pushed me to want to debunk what I thought was a surreptitious move in what was loftily characterised as a “gift” in some Black quarters.

sn’t it funny that when convenient to the cause of white people, Black bodies occupy central spaces in white centred agendas?

Athi Mongezeleli Joja is an art critic with vested interests in the intersection of Black radical politics and visual cultures. He is a member of the Azanian Philosophical Association.

Portrait of Athi Mongezeleli Joja.