The Love Island franchise has had a long running contentious history with its Black stars (or lack, thereof). It was just earlier this year that former Long Island UK star Yewande Biala addressed the micro-aggressions she faced on the show, relating to her name. So, when Love Island announced a new South African edition all the way back in November of 2020, the hype began to build for what would hopefully be something new. However, when the season premier aired this past Sunday February 28 with only 2 Black contestants, there was a fair amount of disappointment. But should any of us — especially black South Africans — be surprised by any of this? Love Island markets itself as “reality TV”, and in reality, they deliver. The precarious lived experience of Black South Africans is the reality which Love Island SA captures so clearly in the pilot episode’s low resolution, orange-graded imagery. Thimna Shooto and Durang Atembe are the only Black characters afforded the luxury of staying at the villa. However, this afforded luxury comes with its own typecasting and representations of palatable Blackness and not surprisingly, the pair form the villa’s last couple. Joining them as the only other distinguishable person of colour is Asad Boomgard.

While Love Island has been criticised for its lack of representational diversity, what the South African version reflects — although we doubt from an intentionally critical or self-aware position — is the proportion of Black and brown people in this country who are able to actually make it into these affluent spaces. Furthermore, the unwritten rules one needs to live by once there to guarantee your stay. To start with, they don’t acknowledge the obvious Black and people of colour to white people ratio. It’s not something you can ignore, nor is it something we want to ignore. Naturally, we make a point of standing together in the strangeness of being a minority in a country where 80% of the population is Black. If these two do take a moment to do just that, we assume it was edited out of the show. While sex, ideal “types” and the contestant’s own relationship histories are all laid out bare on the table, race seems to be the untouchable and therefore unaddressed topic. As disenfranchised members of society, hitting mute on conversations of race clearly isn’t to the benefit of Thimna, Durang or Asad. But rather, the comfort of white viewers and co-stars is prioritised before all.

As could be expected, the stars speak in Afrikaans every once in a while with no added subtitles. Given that the show is based in and presented as something for South Africans, I don’t think there’s any issue with there not being subtitles. Yet, what makes it suspect is that in the 80 minute run of the show, no African languages were spoken. There was no Cape Coloured vernacular English. The brown and Black stars navigate English dialogues with a Shakespearean proficiency. These representations of blackness cast a shadow over the millions of Black people in this country who have never had to navigate many ‘r’s in any given sentence. And perhaps it isn’t that we teach our tongues to twist and turn to make it into white spaces, but rather as a means of working through whiteness and as a strategy to also enjoy access and comfort; fluencies in double consciousness. It’s as real as TV gets. The issue goes beyond lack of representation but also ebbs into how the only two Black contestants are portrayed. Editing, sound effects and camera angles all play a part in creating narratives surrounding each character to frame them in a certain light. In most reality dating shows we are faced with the standard portrayals of different archetypes, the blonde airhead, the gentle giant and in this case the hyper sexualised Black man portrayed by Durang. While the many cuts throughout the show never allow us to hear much of every conversation, a lot of time in the pilot episode was given to showing a conversation between Thimna and Durang. A conversation that seemed to only frame Durang as a cheating player and Thimna as completely uninterested and lost as Durang seems a babbling fool. Why this need to include a conversation that barely makes sense when hours of footage of other conversations could have taken its place?

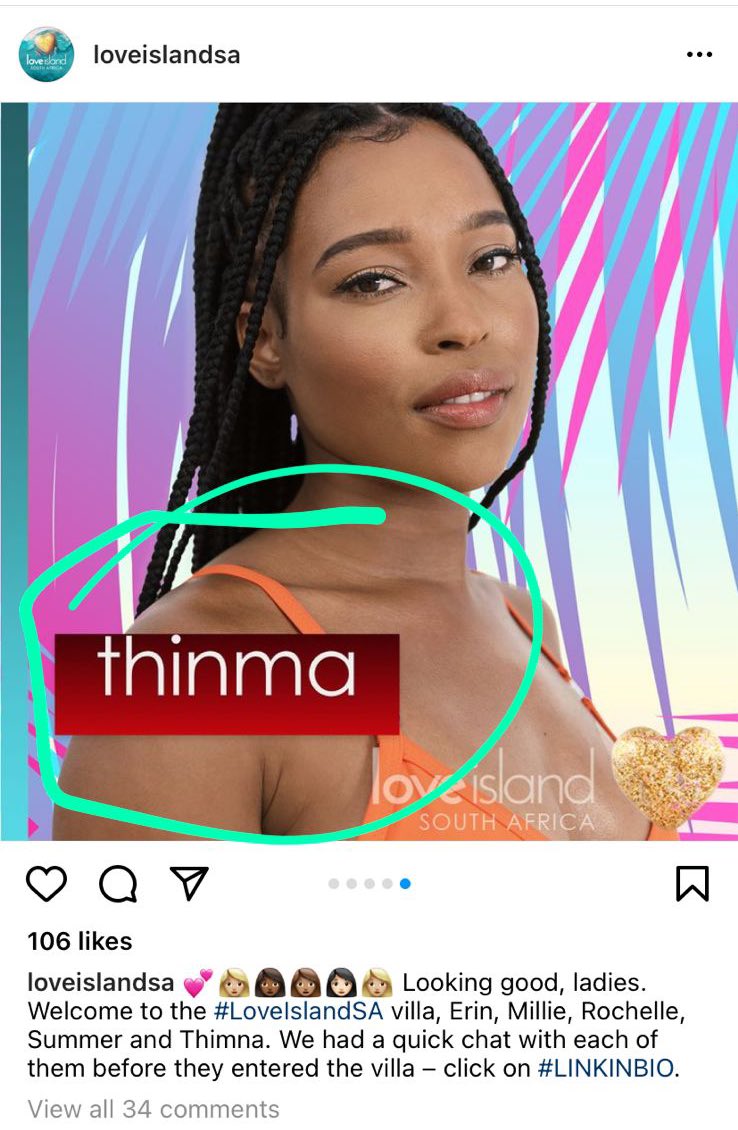

Durang’s portrayal of the hyper masculine, hyper sexualised Black man trope is strengthened by the editors choice to include scenes of him imitating sexual actions in cutaways of the islanders exploring the villa’s shared bedroom. As well as the inclusion of a scene in which Thimna, Millie and Rochelle are describing him as “lusty” “giving me fuck boy vibes” and “very sexual”. Love Island made clear the racial differences and that Thimna and Durang stood out as ‘the other’. In the most obvious form of othering, an Instagram post by Love Island SA themselves introduced all the femmes in the show and spelt Thimna’s name wrong. The reality is that the way this show has been written and structured is not for people of colour nor is it for Black people. The masc islanders, when asked about their ideal partner, describe signifiers that are racially coded, such as “blond hair” and “blue or green eyes”. So we felt the sting of sorrow when Thimna was picked last, it was yet another representation of what it is like for Black and brown femmes. Even in the way Thimna speaks about herself in her behind the scenes introduction as kind and thoughtful plays into how Black femmes and femmes of colour have to be soft and gentle in order to fit into these predominantly white spaces. To not be the “angry, aggressive or cold” one.

The set of Love Island itself is coded in racial nuance and exclusivity, as the host explains when introducing the Villa that what makes the Villa unique is the inclusion of South African words and phrases adorning the walls, words such as “soen my” and “lekker”. The effort to bring in these hints of our South African identity are dismal; words on a wall mean nothing if the show doesn’t actually represent the population of the country. If the rest of the season continues with its angle of othering and framing archetypes we are all in for (prolonged and exhausting) disappointment.