It’s an overcast, yet, warm Wednesday afternoon in Joburg and I’m on a call with President ya straata and Pitori Maradona, Focalistic.

“A se trap ke pina tsa ko kasi”, he says responding to one of my questions as our conversation unfolds — and I think of something said by writer, archivist, isangoma and Ghostland contributor Vuyiswa Xekatwane: “When we think about genealogy and lineage and just how life as a thing – as a function – as an operation is, there is always someone before you. You are never the beginning and the end of anything, even when we come with imagination, creativity and ingenuity, there is something old there.”

For Focalistic, the someone(s) who came before him are all the people who make up Ga-Rankuwa, Zone 2 and the something old, which is his beginning and end, is Pitori.

There is an inspired, impassioned connection and love for this manifold place – Pitori – carried not only in and through Focalistic’s sonic expression but is also one that has evolved as it has rubbed up against and collaborated with the creativity of artists from all over the continent and world.

If music is the sum total of individual and collective experience, then Focalistic’s discography tells the colourful story of a place textured by many lives in a language born from many tongues, Sepitori or the IOS 14 of our 11 official languages as he has dubbed it.

“A se trap ke pina tsa ko kasi”.

Being someone who is a complete nerd for language, it’s capacity, possibilities and disruptions — President ya straata is an artist whose sonic practice and output excite me beyond the space of music. I entered our conversation with no expectations — as I try to do with all of them — and left it moved by the sincerity, humour and thought that proceeded within it.

Below is our offering, from Pitori to the world.

Your musical expression and practice seem rooted in home as a point of departure. By home I mean both the African continent but also the specific locality of Pitori, Zone 2, Ga-Rankuwa where you’re from.

In what ways would you say your sound and way of making music have been influenced by growing up in Ga-Rankuwa, Zone 2 and by music from specific African countries?

Focalistic: I think that as a point of departure, you saying ‘Ga-Rankuwa, Zone 2’ is very important because that’s where “A se trap ke pina tsa ko kasi” comes from. For me growing up, the most inspiring times were the times I stayed in Ga-Rankuwa, when I stayed in Pretoria because those are the times that moulded me into who I am right now.

So, I kind of utilised that frame, always thinking about how it would be if I was still there or think about whether this or that person could survive Ga-Rankuwa? That’s what inspires my music because that’s what moulded me, and the type of hustler mentality I have is born from there.

Pitori is a hustle and bustle kind of place, as much as people always say Joburg [is], it’s Pitori for me that’s structured the way I think, which bleeds into how I make music and the sounds that I like. You know in Pitori, one car is playing Tamia and the next car is playing Skupu or Mujava, so even my musical sensibilities are inspired by Pitori.

When it comes to the continent, having travelled early in my career is one of the best things to have happened to me but especially for my ear, and learning different dances to connect with the different rhythms the people on our continent move in.

I think that once I started understanding that, along with coming from Pitori and fusing those knowledges and experiences, I tapped into the journey that led to me being this Focalistic in 2022.

As much as there’s a point of departure we’re not stagnant, there’s also an awareness that as people and artists we keep growing, learning new things and evolving. So I took Pitori, mixed it with Pan-African sonics and it led to this sound people are calling “the champion sound” right now and that’s been the fastest spreading song in my career.

What you’ve just said about the multiplicity of what inspires you — about how, yes — there is a point of departure but we don’t stay stagnant. It’s also about moving forward and imagining something new, this leads me quite nicely into another element of your sonic practice I wanted to chat about.

Your music moves between so many different genres, so defining it in the absolute becomes tricky. Would you say that genre is helping or hindering us, especially as African people whose creativity and ways of being in the world are not binarised? Do we need new ways and words to speak and think about music?

Focalistic: I mean, I definitely have never been an advocate for genre and its separations. To this day, when people ask me “so what genre of music do you make?” I say, “Genre ya’ka ke ‘a se trap ke pina tsa ko kasi.’” Which is also why I brought up the example of one taxi passing playing Tamia and and next one will be playing amapiano and with the next passing taxi we’re back to Bacardi — so personally it’s never been about one particular genre.

I also think that’s what creativity is, fluidity, once you think within a box you limit yourself and I’ve never been one to limit myself or my creativity. I think that’s why after being the number one hottest MC in South Africa, I had to unequivocally state that I had actually quit making hip hop because I felt like that was a box I didn’t want to be contained in.

It’s one of the decisions I’m super proud of; I can rap if I want to but I feel like it removed that expectation to be “a rapper” and people could start acclimatising to me as an all round artist. I think genre is definitely a limiting fact and can limit creativity.

Mmm, I feel you. So there’s something that piqued my (questioning) interest a while back while listening to President Ya Straata, it happened while listening to your song featuring Mellow and Sleazy “Bacardi Ke Religion”.

Sure, it’s the name of the song but it also seems like it’s so much more than that, and perhaps it’s because I’m not from Pitori, so I can’t access the kind of knowing that comes with belonging to or being from a place right?

So Bacardi Ke Religion, how, why — is it speaking to a way of life, a culture, a sound..?

Focalistic: Yeees, yes yes! You know, when I made the song I was in Ghana. I couldn’t come back home because I had to go to London and needed to be quarantined for 14 days before flying there, so it was kind of a sad period because you’re alone with nothing to really do because you’re isolated. Luckily I had travelled with my studio and just being in Ghana, observing the environment and speaking to different people, I just realised that my religion ke Bacardi — religion ya’ka ke Pitori, you know?

That’s where I come from, that’s what I represent and that’s what I miss when I’m a 6 or 16 hour flight away, ke religion ya rena — ke culture ya rena. When people ask me “what is Pitori?” I always say that Pitori ke culture. You can spot a person who comes from Pitori from a mile away, around the way — when I made “Bacardi Ke Religion” that’s what it was all about.

I felt like as we travelled around the world we stuck out and if you were from Pitori you knew that these guys are definitely from Pitori, from the walk to the way we dress and then obviously when I start speaking like die maan, wang tswara?

Another thing, if you listen to the song’s medley, I’ve taken it from a Mujava song as a way of paying homage to people and elements that went into my own making.

As we’ve been speaking, I’ve been wondering if you think of yourself as a Pan-African artist, and what Pan-Africanism and Pan-African collaboration look like to you in this contemporary moment?

Focalistic: I definitely am a Pan-African artist, I will say though that I didn’t start off with the intention of being one but that also makes me an important voice within the Pan-African space. I started off in my space, I started off in Pitori representing one hood and wanting to make the people from there so proud that they want to share me with the world.

That’s what I mean about my music practice being important in that space. There’s a need — even within Pan-African sonic movements — to hear the different stories, whether you’re from Nigeria and I’m from South Africa. That’s why the “ke Star” remix is one of the biggest Pan-African songs right now, it’s a true testament to the importance of Pan-African collaboration.

I also think that’s why people are so excited about mine and Davido’s “Champion Sound”, you get to hear two different sides of a story on one song.

I’ve always been an advocate for Pan-African collaboration; I think it’s about unifying Africa yet still staying connected to the stories and creativity of where you’re from. So you’ll have a [moment] when that creativity and those stories come together, we [then] have what you can call an African national anthem, and we can create many more African national anthems that way.

You studied political science in university — and I wonder if the visual aesthetics for President Ya Straata were influenced by this?

Not to say that you make political music because I also think that there’s this lazy and constraining relationship the world has with Black artists where it can only engage with Black artistic expression from the point of the political.

But still with all of that said, I still think things as mundane as our laughter and joy as Black people can be implicitly political without trying to perform a particular politic. So, would you say that there are political undertones to your music and the aesthetics that come from it?

Focalistic: Yeah, for sure, sometimes it’s not about trying to disturb the system in overt ways, I see politics as everyday life. I guess, you may be right in saying it’s because that’s what I studied

So me being President ya straata was basically me realising that although I had studied Political Science — with an aim to change a couple lives and make sure that people from my hood specifically are progressing to a better place — even our politicians are human beings, so I can be a human being and change many more lives through a different avenue, which is music.

If you listen to “Peer Pressure”, there’s a part in the song where I say “ke tjhentjhitse maphelo a mabaya ka dipina” (I’ve changed many lives with songs). I guess that was my realisation, I also think there’s a maturity to that EP, every time I listen to it I unpack its lyrics in new ways — which has led to an understating that I’ve been able to impact many lives through my gift of words and in, that express my political duty to the world.

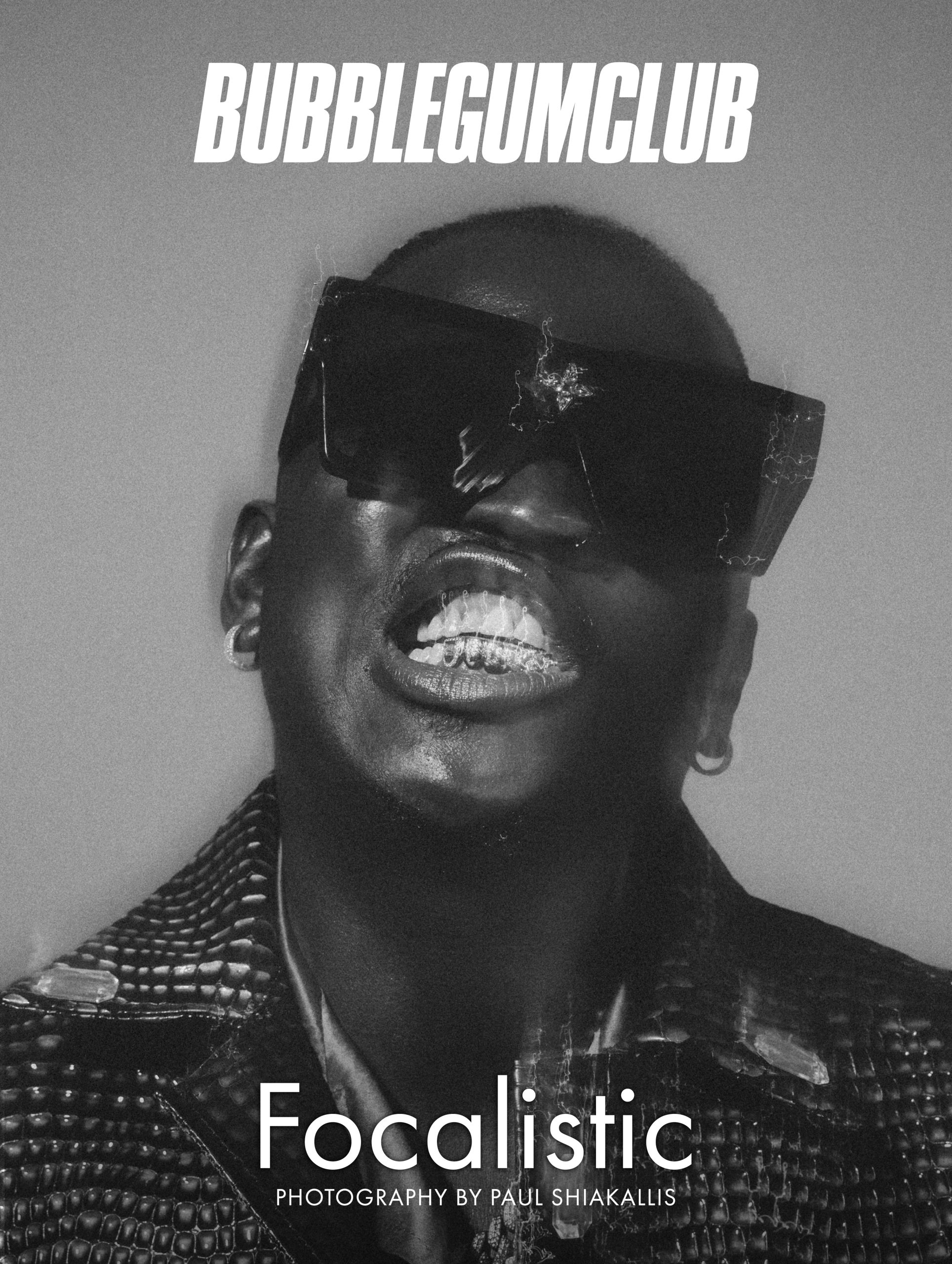

CREDITS

Photography by: Paul Shiakallis

Creative Direction by: Jamal Nxedlana

Styled by: Siyabonga Mtshali

Makeup by: Aimee Lokota

Written by: Lindiwe Mngxitama

Producer: Moipone Tlale

Videographer: Lex Trickett

Content Creator: Joy Anelisiwe Mahamba