I look at an ant and I see myself, a native South African endowed by nature with a strength much greater than my size […] I look at a bird and I see myself, a native South African soaring […] on wings of pride, the pride of a beautiful people. I look at a stream and I see myself, a native South African, flowing irresistibly over the obstacles until they become smooth and one day disappear – flowing from the origin that has been forgotten, towards an end that will never be.

– Miriam Makeba, Makeba: My Story

Let it be known that we have been travelling and finding slippages and strategies of possibility and mobility despite oppressive power structures to create and influence the world since the beginning of time.

– Gallo Vault Sessions, South African Music Goes Global

When it comes to the trade of music, Amapiano has been one of Africa’s most popular exports since 2019. With Spotify streaming outside of Sub-Saharan Africa increasing by more than 563% over the previous two years, Amapiano is the most recent South African music genre to put its musicians on a worldwide scale. In May of this year, six African artists joined Spotify’s RADAR program, which is a platform for the promotion and discovery of up-and-coming musicians with global appeal.

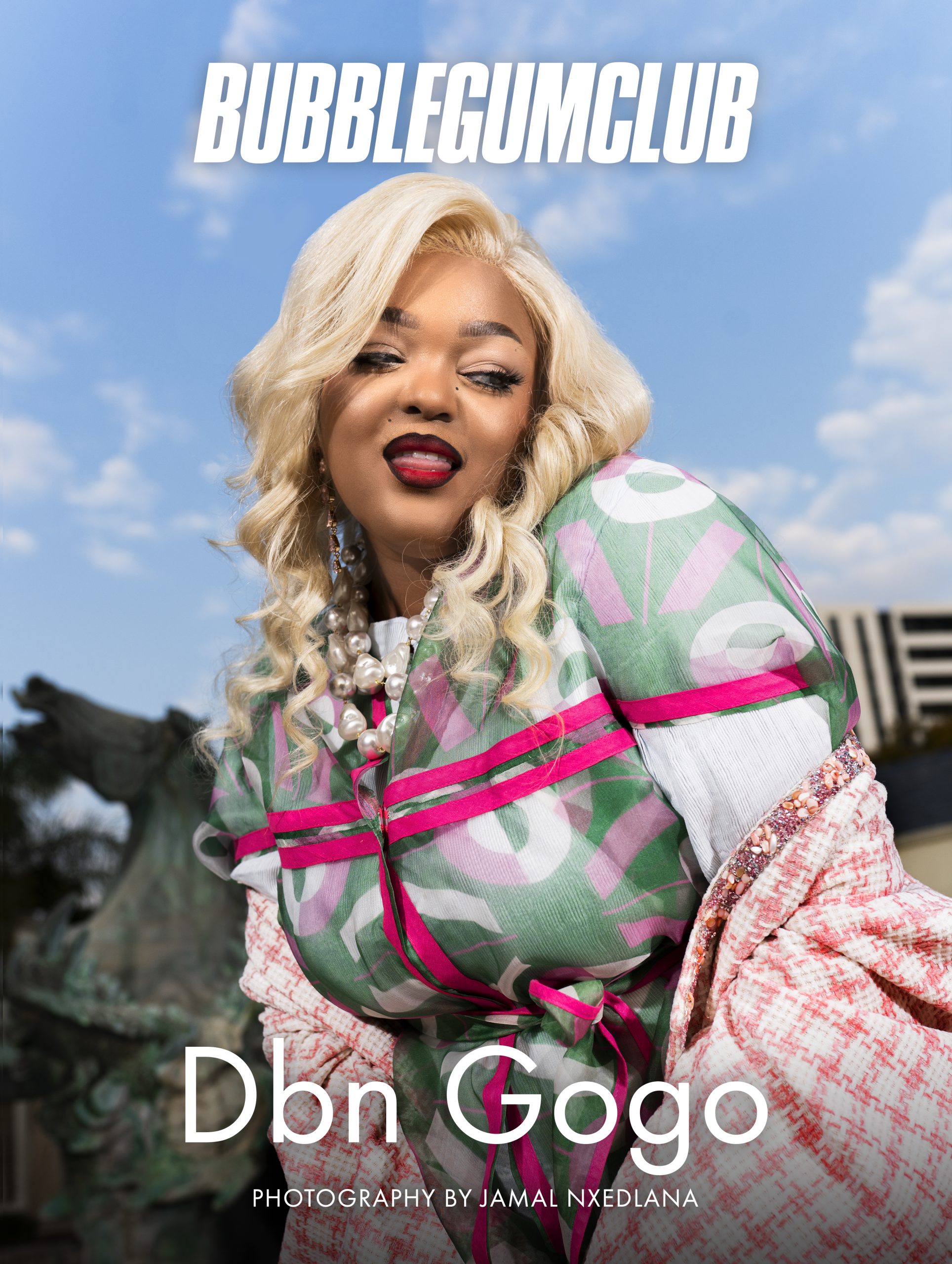

DBN Gogo, Ayra Starr, Black Sherif, Victony, BNXN, and Buruklyn Boyz make up this year’s cohort of RADAR Africa artists. This group of musicians follow in the footsteps of previous African artists such as Elaine, Willy Cardiac, Tems, and Focalistic who all joined the program in 2020 and grown their international audiences.

Like so many before her, Mandisa Radebe – also known as DBN Gogo – began her career in music as a child, learning and being emersed within the musical culture of her surroundings.

“I have always been a musical kid. I spent some of my childhood abroad in France as my mother was an ambassador at the time. All the South African artists that came to Paris to perform would always end up at my house at some point when we were in France”, she mentions. “Music has always been a big part of my life. It’s my greatest gift. I grew up singing and taking dance classes. Music has always made me happy and made sense to me”, she continues.

The connection of the then and now, appears more than expected in DBN Gogo’s life as there is a personal connection to her and one of the many artists who were sent to exile at the height of Apartheid – Miriam Makeba. “I grew up having lunch with the late Miriam Makeba at least once every Sunday because she loved my mom’s fish.” I ask Gogo about this connection and what, to her, it means to be a South African musical export, though under more politically liberated circumstances but in a similar vein of global empowerment to those who have come before her. “It’s unbelievable more than anything”, she replies.

There are multiple examples of genres in the country crossing the seas, influencing not only African but global musical culture as well, however, there is something spectacular and fantastic about the progression of Amapiano.

When I started DJ’ing, I knew I had to make it work. I’ve worked so hard to get to this point that I am at today. I’ve had so many sleepless nights and now it is all paying off. Who would have thought that little Mandisa who used to sing and dance for her family as a kid would be headlining places in Greece, Paris, London, Tanzania, Ghana, and other countries?

It’s surreal, it’s not every day that you get to wake up and do what you love on a global scale. I really hope I can continue to touch and inspire many more individuals with my craft.

The story of musical exportation intended and facilitated by Black people in the country is rich with a history that dates back to the success of choral and theatre musicals in the early 1920s. The blues and Jazz, particularly the music of the 1940s and 1950s, are well recognised and continuously reinvented. Even techno-rave and house music have developed localised varieties that have staked their claim on world stages. Hip-hop and Kwaito, which combine elements of Rap, Reggae, and other musical genres into a uniquely South African style, have been particularly successful. With Gqom and anything that is bred from the lived reality of the Black majority (re)defining culture in the country and beyond.

Amapiano is truly a product of its history – a continuation of lineage.

“It’s just like any other art form,” Gogo proclaims. “It’s an escape for anybody who listens to it, it’s a means of coping for others and it is a way for people to express themselves. It’s not just the music that’s important, it’s the dance, the style, and the people.” If you ask any Amapiano practicing artist in the country, they will tell you that Amapiano is more than just a mere sonic endeavor, particularly one reduced the moment. Easing to my curiosity about exactly why Amapiano can be considered a way of live, DBN Gogo responds:

It’s inspiring, sort of a promise of a better future. There’s soulful jazz-like piano, there’s Bacardi piano, afro piano, kwaito piano, and many other variations. I believe listening to piano just allows one to gravitate toward happiness. It allows you to numb your pain. And at that very moment, none of your problems seem to matter.

As someone who follows music cultures and moments as they come and pass, I get a little bit disheartened when it seems as though as young people, we are a collective and community of the now. A puff and pass if you will – much less sustainable but still just as exciting. We’ve come across a great number of musical movements in South Africa and Africa as a whole. We move through moments and genres almost in a circular motion – celebrating every time we come across a genre such as amapiano and an artist such as DBN Gogo.

However, what does that say to the sustainabilty of practising popular music in the country, not to mention the systemic implications of placing artists and groups into catagories that serve us ‘now’ and no more than later? A question of relevance and binaries arises to me as well as whether Gogo herself is at all aware or concerned about amapiano and this phenomenon.

I think you guys would faint if you knew. If I set my mind to it, I can and will do it. I don’t just play piano. Ask Until Until and they’ll tell you, I give a very nasty Afro tech set when I’m asked and you can ask DJ Venom (Sondela) if I know how to put down some hotlines and he’ll tell you what’s up.

I wouldn’t say being known as a piano artist is hindering me as an artist because piano is so big. I’m not blocked by just being known as the “piano lady” or anything like that. There are so many sub-genres to the genre. I also think even more variations are going to come out of it seeing as how well we are exporting it to the rest of the world.

One thing I have no doubt about is that South African artists influence the world, repeatedly, time after time. I do not wish to clear up any misconceptions about South African artists other than any ideas that allude to them being parochial, DBN Gogo herself included.

The next logical inquisition is the future. Out of my slyness I want to know what Gogo has got planned and as a key player, what trajectory she sees us going into next. “There is no telling regarding what I see our music culture expanding to. All I know is that it’s going to be like nothing we’ve ever seen before. When I look back to the start of the piano era, I find myself laughing sometimes because it’s honestly unbelievable how far we’ve come.”

This sentiment I acknowledge and agree with. There has been such a movement already from what the mainstream audience considers ‘the beginning’ of amapiano that our ideas are almost laughable to people who have been following amapiano since before it even charted. Who knows where it is going next?

When it all began, we never expected it to blow up the way it did. Piano was for us, and now it’s literally for the world. I wish I could look into the future and tell you exactly how crazy it’s going to be, but I have to wait and see just like everyone else.

I hope that as the culture expands, we meet and create more artists. I also hope that we can find more ways to ‘consume’ the culture, there are other ways we can touch and reach more people. I think it can go further than just music and dance.

Since its debut, RADAR has strengthened connections between fans and artists. As part of the initiative, Spotify will provide these artists with editorial, on-platform, and off-platform support to help them grow their unique fanbases. Additionally, Spotify will prioritise the promotion of RADAR playlists, RADAR podcasts, Spotify Singles, and priority releases from RADAR artists across all countries as part of the debut of its Global Hub.

This article is in collaboration with Spotify and Universal Music

CREDITS

Director & Photography by: Jamal Nxedlana

Lighting by: Paul Shiakallis

Lighting Assistant: Blessing Ndlovu

Retouching by: Lightfarm

Styled by: Louw Kotze

Styling Assistant: Nombuso

Makeup by: Tammi Mbambo

Hair by: Ncumisa Mimi Duma

Producer: Moipone Tlale

Videographer: Lex Trickett

Editor: Ayabonga Magwaxaza

Sound Design: Zamani Xolo

Interviewed by: Joy Anelisiwe Mahamba