“When you say ‘Black is beautiful’ you are saying, ‘Man you are okay as you are, begin to look upon yourself as a human being’.”

Steve Biko

Stories of freedom and liberation are not without their accompanying Ghosts — drenched in the blood, sweat and tears that our ancestors sacrificed as resistive offerings for our future(s). On the 27th of April 1994 South Africa held its first democratic elections and with this, people who were not previously considered South Africans, became citizens. This ushered in by the dignity and humanity the right to vote is said to imbue. This is our history of revolution woven through struggle.

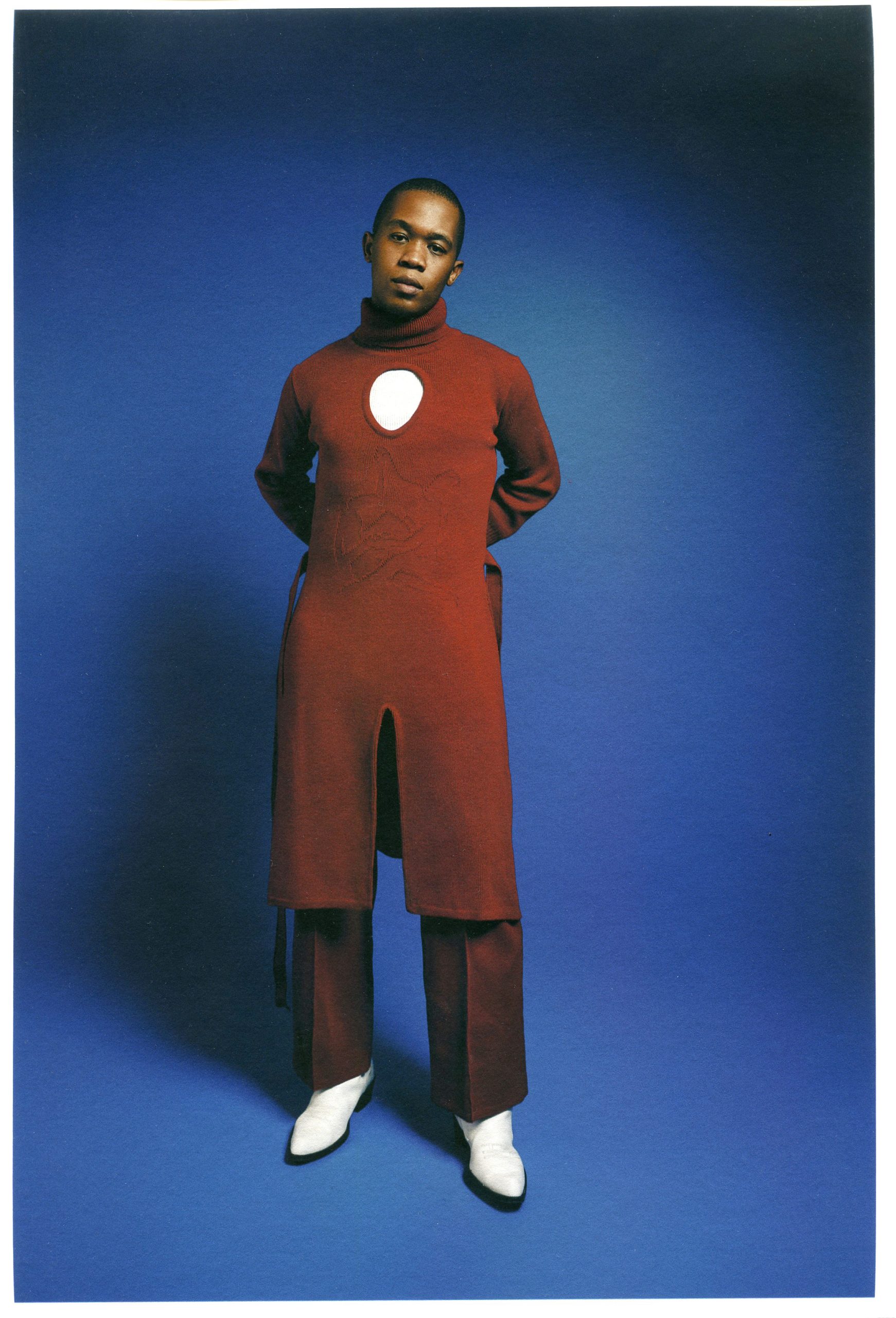

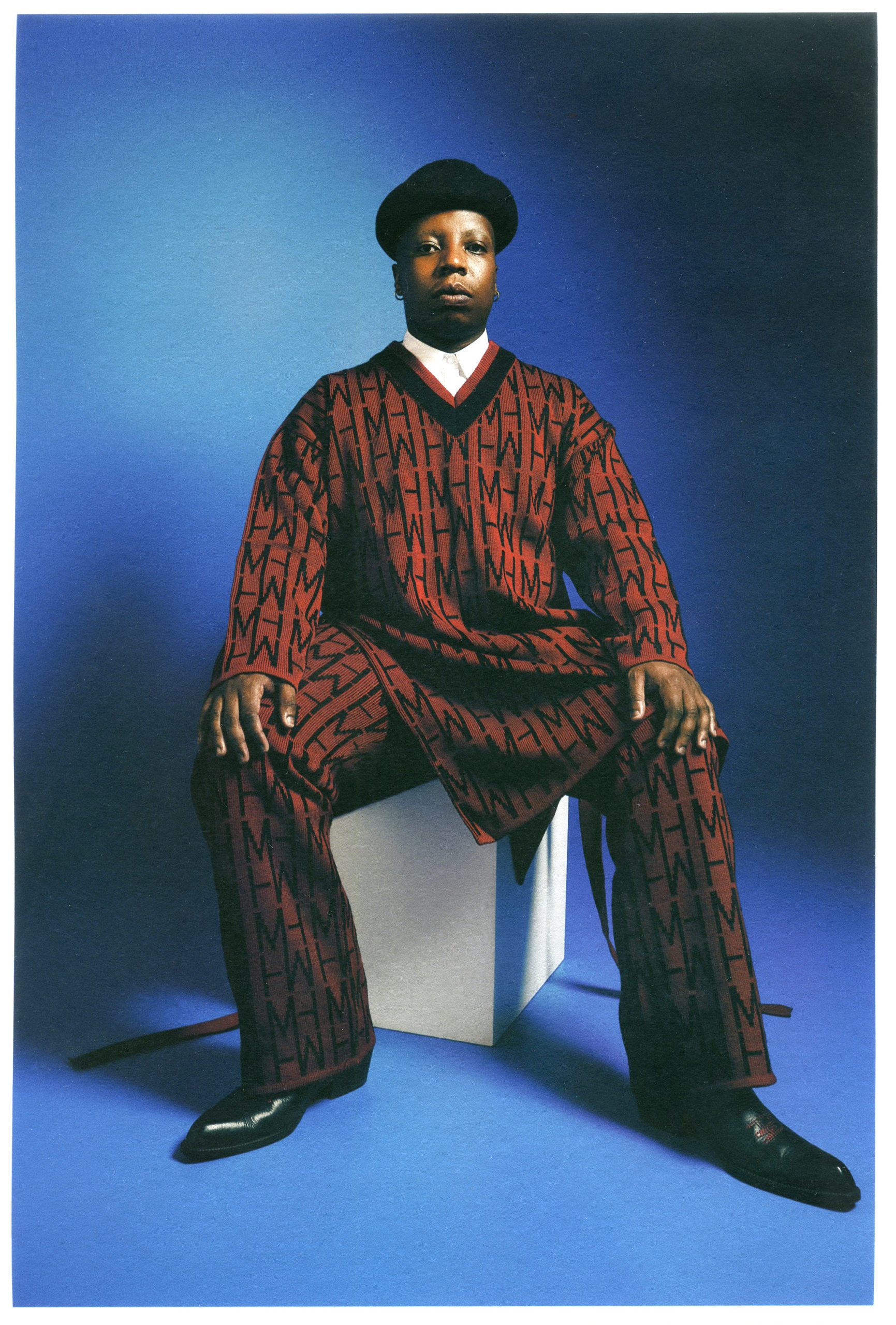

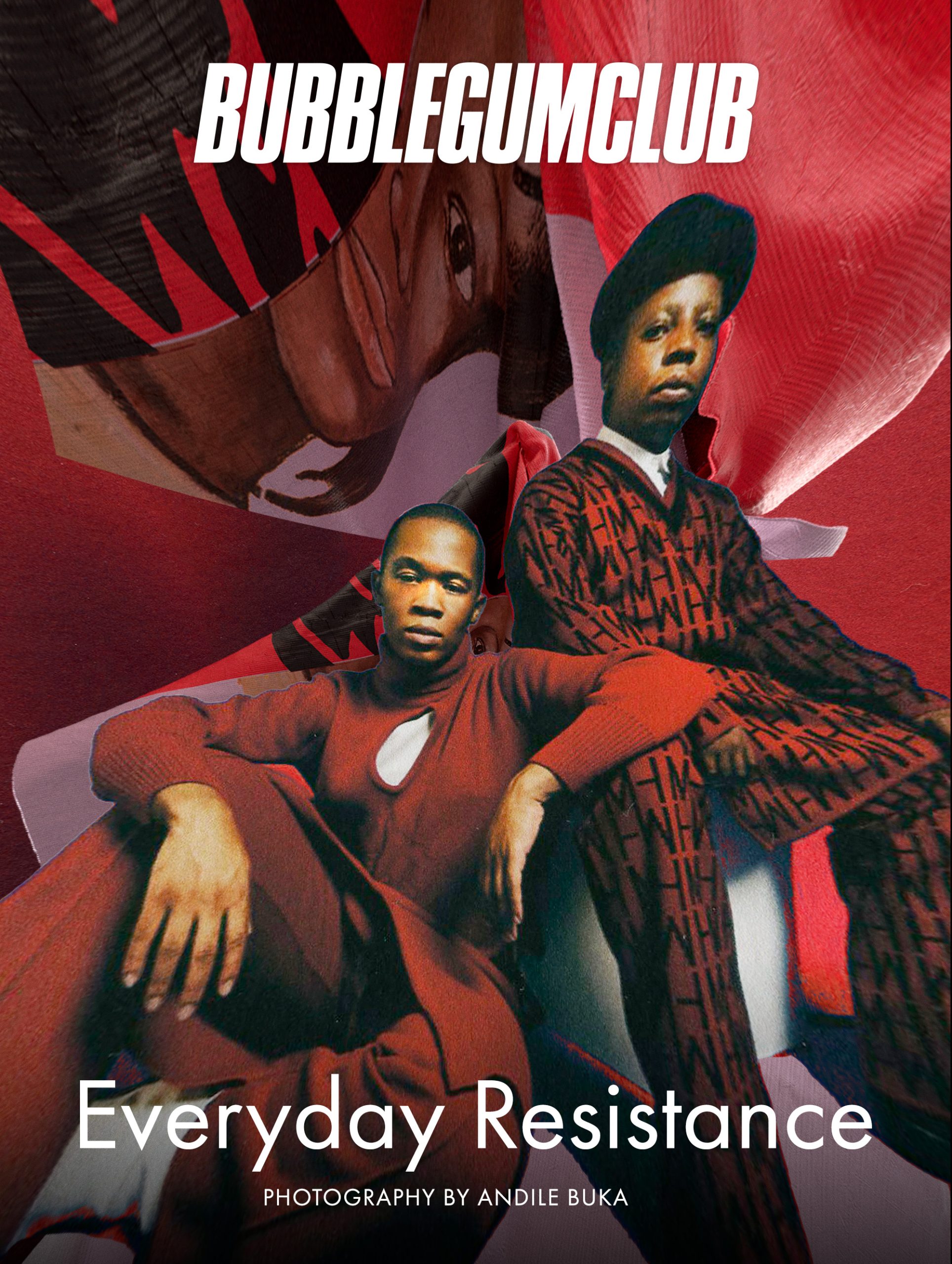

Thebe Magugu and Wanda Lephoto are brands both rooted in storytelling and in documenting culture — with an approach to creation situated in rememory, intimate, affective archival work and turning towards home and homing as life affirming sites of reclaiming our histories and ideas of Self, declared shameful by exogenous socio-political and historical forces.

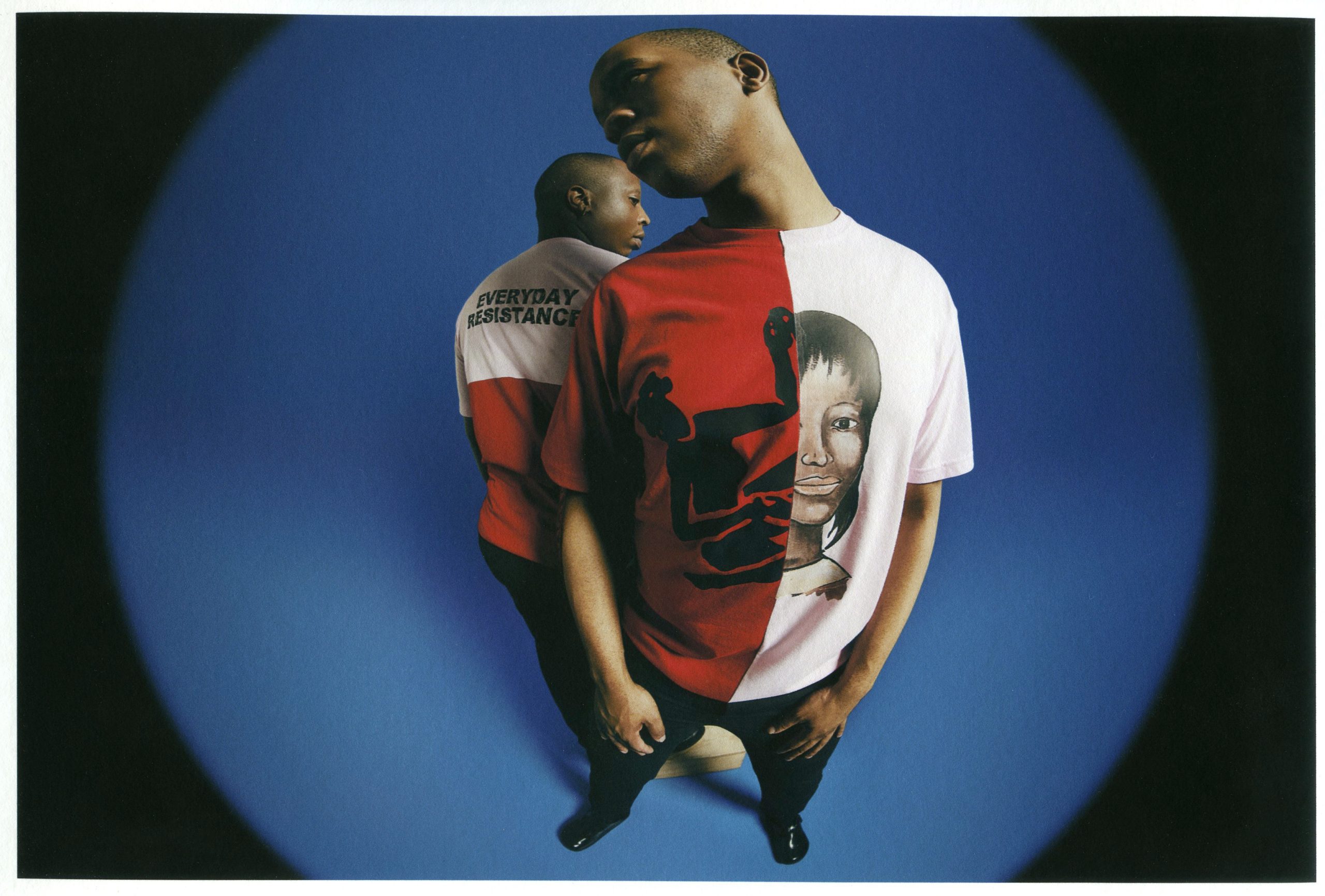

Historically, printed shirts have existed as sites of resistance, and in carrying on the tactile tradition of looking to ourselves and our stories for inspiration and hope, Magugu and Lephoto have collaborated on a new t-shirt. The collaboration — under the name Project 16.1.C — is inspired by our South Africa’s Bill of Rights, specifically the clause articulating the right to creative expression and individuality.

While “language can deform actualities” — other spaces of expression such as fashion — hold the capacity to “speak” truer truths of our stories. Perhaps, this is why fashion has also historically been a powerful medium of inciting change.

As we hold collective memorial for those who sacrificed their own futures for ours and as we celebrate our hard fought for freedom — I spoke to Magugu and Lephoto about the past, present and future — and about the significance of their Project 16.1.C collaboration.

THEBE MAGUGU

PAST

Lindiwe Mngxitama: In Blessed Being Black, artist and filmmaker Arthur Jafa makes a declaration about his work and practice saying: “If there’s a political dimension to my practice, it really is about trying to destabilise the mechanisms that try to make us come to whatever conclusion they decide we should come to — about what’s happening in the world.”

I carry Jafa’s sentiment with me, as a thinking companion, for our conversation. I think about one of your last collections, Genealogy — which I would argue that, from the name to the concept of the show, was quite explicit in the (re)memory and archival work it was doing.

Speaking about the collection you have said, “It’s this idea of memory as a reservoir for optimism.” All this said, would you say that your work has a political relationship with memory, intimate archival sites such as family photo albums and optimism? Specifically where Black people in South Africa are concerned and our relationship with histories that have sought to control and erase us?

Thebe Magugu: When I was younger, I used to see my reality through the lens of shame. My mother worked extremely hard to get me into a good school but being around pupils who were extremely privileged made me quite critical of my own circumstance. I was also already an avid follower of fashion, which is based off everything we didn’t have and everything I was not. Now that I am older, I use my brand as a reclamation device — taking all the things that used to embarrass me about my lived reality and elevating them into a luxury space.

My practice is about finding beauty in the banal and the elevation of the everyday. I think this makes my brand sit at an intersection of memory and socio political ‘magical realism’. In other words, using my past — which is coloured by apartheid era circumstance — removing the colonial lens underprivileged people often are forced to view themselves under, and projecting that as its own status symbol.

It’s a paradigm shift I wish I had when I was younger but through my brand, I find I am readdressing and re-imagining the black experience; one that was so impinged onto by the regime before. I do this through collections that produce physical relics — for now, and for future generations — to refer back to.

PRESENT

Lindiwe Mngxitama: There is this sense — exuded both by Thebe Magugu the person and THEBE MAGUGU the design house — that there is a way of being in the world and creative methodology rooted in acute intention, where every detail is considered and with each element serving an individual and collective purpose. In harmonious synergy.

From a speculative place, would you say that this is influenced by you being raised in a matriarchal household, by your grandmother, mother and aunt? How does their influence live through your work and practice today?

Thebe Magugu: This is an interesting question because it speaks to my current exploration of clothes belonging to a family, not just an individual. Growing up, I saw a blouse circulate between my grandmother, my aunt and my mother. However, that blouse took on a different energy with each person. I think this is where my appreciation for ready to wear came through — that across various generations, its purpose still remains the same while allowing various personalities to shine.

Clothes done right don’t eclipse their wearer. In addition, functionality is also quite important in my work because I saw these matriarchal figures juggle home, work, church and children, with all that comes with — their clothes couldn’t impose and hinder. They needed to aid in the day to day.

As a thought running alongside this, I think ‘Documentation in the Black Home’ was also a guide for the brand as well. There is a system, even if it’s birth certificates and deeds divided and placed under the mattress or in a series of vanity cases, of extreme organisation. It’s a methodology reflected in the encyclopaedic approach the THEBE MAGUGU brand takes.

FUTURE

Lindiwe Mngxitama: Looking towards the future — of fashion, of our country, of Black history and stories — what would you say is at stake in (re)imagining what is possible where THEBE MAGUGU is concerned.

Thebe Magugu: As black people, there have been so many instances in our history where our pride, our identity and our culture were invalidated and made to translate us undesirable. Fashion has a unique ability to not only reflect a time but to also redefine perceptions, and it’s what I want my clothes to do — suggest a pride, regality and sophistication — we have constantly been denied but have always carried inherently. I find that is what a lot of black designers are doing, all the things we were called ghetto and trashy for, those things are being renegotiated and are finding themselves manifest at the height of luxury.

Lindiwe Mngxitama: I get the sense that collaboration will be informing a large part of your creative strategy for this upcoming year. Why this development and what intention is it rooted in?

Thebe Magugu: I have always been excited by different intersections and the magic that sits there. One of my favourite photographers Sølve Sundsbø , to paraphrase, spoke about how, “we have seen ninjas fighting in shoots, we have seen underwater shoots — what we haven’t seen is ninjas fighting underwater”. This sounds simple but I find its lesson to be quite powerful — when you begin to merge references together and to decontextualise certain scenarios, a powerful imagined reality happens.

Collaborations, especially from the POV of emerging designers, have always had a power dynamic between ‘big brand + young designer’ pairings. What happens when two emerging brands, with different visual signifiers, come together? It’s that pursuit of newness I keep referring to, upending accepted norms and terms around fashion collaborations. This doesn’t also need to be limited to fashion — which is where really exciting mergers start to happen.

What is fashion through the lens of architecture? Aerodynamics? Automobiles?

With Wanda Lephoto, I deeply respect his approach; telling stories of familiarity and family through menswear. I find we both share that common thread — homages to current day South Africa. He was the perfect partner to begin this series of annual [MICRO]LABORATIONS.

WANDA LEPHOTO

PAST

Lindiwe Mngxitama: I asked this question to Thebe in relation to the relationship with (re)memory and archival excavations his designs and practice signal towards, more explicitly where his Genealogy collection is concerned. Looking more specifically at your recent collections, such as Home Affairs, would you say that there is a political relationship your label and practice has with sites of home or homing — as places of identity and meaning making?

Wanda Lephoto: I don’t often think about my work as having a ‘political’ relationship with sites of home or homing as places of identity, and perhaps, they do exist in a way I myself have yet to understand.

I do nonetheless think of home or homing — especially with regards to identity — as a place of question and discovery. The idea of what questions I can ask about who we are. that can allow me, and us, to discover languages and codes of what makes us who we are. And how fashion allows me to navigate through those conversations.”

I’ve been thinking of the words I’ve been saying lately, of needing to rid ourselves of embarrassments that embarrass us, especially in relation to my work and thoughts. The idea that although we don’t come from what we or the world may consider or define as “beautiful homes or histories”, we are still able to create beautiful things with meaning as a response to purity or pain, trauma or beauty, perception and truth.

I think my work seeks to at times reveal more than anything else. The truths about our shared histories and journeys, that we often overlook and sweep away because of discomfort about who we are and even more so, how we are.

PRESENT

Lindiwe Mngxitama: There is another declaration made by Jafa stating:

You want to make things that function on multiple levels — that’s all I mean by complexity…When I say “oh, I want to make something that’s available to multiple almost divergent readings.” Cause honestly I’m not interested in telling people what to think, I just want to make things that make people think and make people feel things intensely.

In this vain and at this present moment, what types of clothes are you interested in making or move with the intention of creating? And with that said, which stories are you weaving through and with them?

Wanda Lephoto: My relationship with fashion and clothing has been very slow, my understanding of it even slower. My relationship with beauty — the beauty of the world and of fashion — in relation to who we are, where we come from and where we’re going has been the slowest.

I attribute that to this relationship I speak of; this idea of purity or pain and trauma or beauty.

As it stands, I am interested in introspecting on these relationship: the ANC t-shirts, the barbershop and salon graphics; the Shembe, ZCC church inspired garments that question the colonisation of South African Churches, Home Affairs collection in response to our GAZE of immigrants, refugees, conversations around xenophobia, homophobia, transphobia and other phobias that we as South Africans and Africans have as a justifications for our actions or questions of our identity. All of these conversations explored, with the understanding of needing to question if these things exist in my eyes or the world’s eye as responses to trauma or pain?

With all that said my clothing right now is only a reflection of who I see us as in the everyday common ordinary place — from my fabric choices, to the design styles, shapes, silhouettes and styling — it’s who I see us as, reflected and not imagined. To me, this is beautiful, although it is layered and nuanced with a lot of intricacies relating to pain.

I’m learning, especially when it comes to beauty, to reflect these reflections I see and to turn them into something different. Hopefully with the upcoming seasons, it will go to a place of an imagined beauty as a true response to our future.

FUTURE

Lindiwe Mngxitama: Looking towards the future — of fashion, of our country, of Black history and stories — what would you say is at stake in (re)imagining what is possible where WANDA LEPHOTO is concerned.

Wanda Lephoto: Truthfully, my life. All of our lives are what most of us give to make things work — our lives.

I don’t necessarily think I personally have to (re)imagine the possibilities of the future of where WANDA LEPHOTO is concerned as my validation comes from self, family and friends. I understand that I do what I do whether the cameras are off or on, and regardless of whether the stockists are buying my shit or not. I pay that price with my life and in many ways, most of us do.

I look at Thebe’s work and that is what he is giving, his life. Collections and conversations that speak to his family and his birthplace. Conversations around the historical importance of certain people, places and events within our continent and specifically South Africa that matter so much, that’s his life that he is giving and it is beautiful to watch and to be inspired by.

The future of fashion, of our country, of Black history and stories — at least to me — is who we all are collectively, from bigger brand names to emerging ones. The future of fashion, of our country, of Black history and stories is the truth in which we are able to speak about where we are and where we want to go and how we can get there. To me, we all are the future of these things that matter so much to us, regardless of whether we all get celebrated publicly or not.

Lindiwe Mngxitama: What does this THEBE MAGUGU X WANDA LEPHOTO collaboration mean to you and how do you think we can reshape our relationship with collaboration away from the exploitative logic of capitalism and reconfigure it in more egalitarian ways, possibly even drawing from indigenous concepts such as Ubuntu?

Wanda Lephoto: This collaboration means so much to me, besides getting to collaborate with Thebe who I love, respect and am inspired by, it means so much to me that we get to collaborate on FREEDOM, something that means so much to the both of us.

Historically, many of the limitations faced by our people were bound to FREEDOM and not having any to be able to advocate for their deserved humanity.

Project 16.1.C speaks to that idea of FREEDOM, the FREEDOM that has afforded us the opportunity to be able to fight for our dreams. Thebe and myself have always used fashion as a vehicle to document culture, especially through storytelling and Freedom Day is of critical importance to that process.

Personally, it’s hard to speak to the exploitative logic of capitalism. I believe we’re all still learning how to navigate ourselves through life, and in many ways figuring it out as we go, because of our intentions. Our intentions are rooted in wanting better for each other and ourselves and collectively. Concepts such as UBUNTU have shaped the foundations of those intentions.

*Information on where to purchase the t-shirt shall be provided soon.

CREDITS

Photography by: Andile Buka

Creative Direction by: Jamal Nxedlana

Styling & Direction by: Amy Zama

Creative Production by: Moipone Tlale

Written by: Lindiwe Mngxitama

Makeup: Aimee (Bobby) Lokota

Retouched by: Ashiq Johnson

CGI: Lex Trickett

Production Assistant: Joy Mahamba

Lighting Assistants: Kgomotso Neto & Amanda Buka