High peasant, premium mediocre, domestic cozy and thrift store (favela chic) are the four aesthetic movements theorised by writers Venkatesh Rao and Nils Gilman to capture the cultural visual age we are currently living in.

Picture a graph with a y-axis and an x-axis. On top of the y-axis are the words ‘high cost’ and at the bottom of the y-axis are the words ‘low cost’; on the left of the x-axis are the words ‘private pleasure’ and on the right are the words ‘public display’.

This graph — presented by Rao — basically suggests and summarises where each form of current mainstream fashion expression lies, including brands, labels, aesthetics and personal style.

What dictates fashion in this century, more than anything else, is accessibility (cost to attain) and who is targeted to be on the receiving end of that expression (public or private).

These aforementioned aesthetic movements are theoretical suggestions; theoretical suggestions of which with some palatable examples might prove to be quite applicable and accurate.

So let’s begin with the first one, what is ‘high peasant’? Where do we see ‘high peasant’?

The term ‘high peasant’ is a fashion term derived colloquially from sociology which is understood to mean an aesthetic or style that visually presents itself as low quality (poor) or of low economic and social status but has come to be through the use of high resources.

As artistic director Akili Moree puts it, this is also known as “cosplaying as poor”.

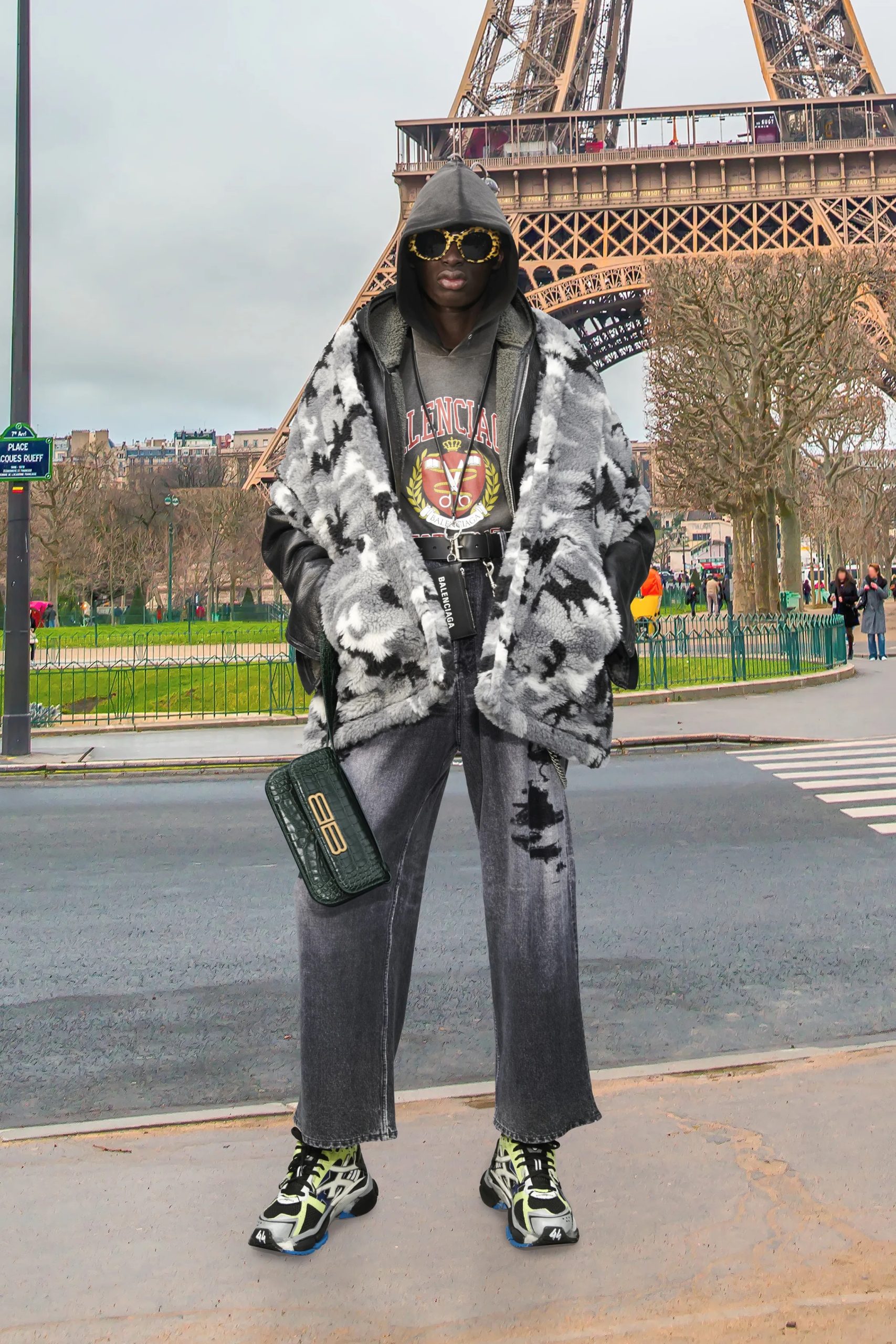

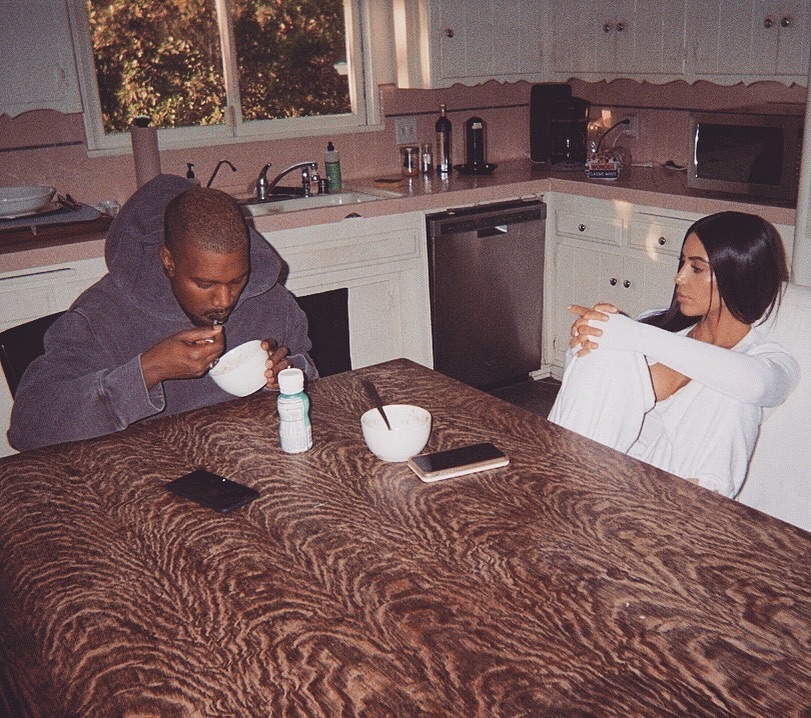

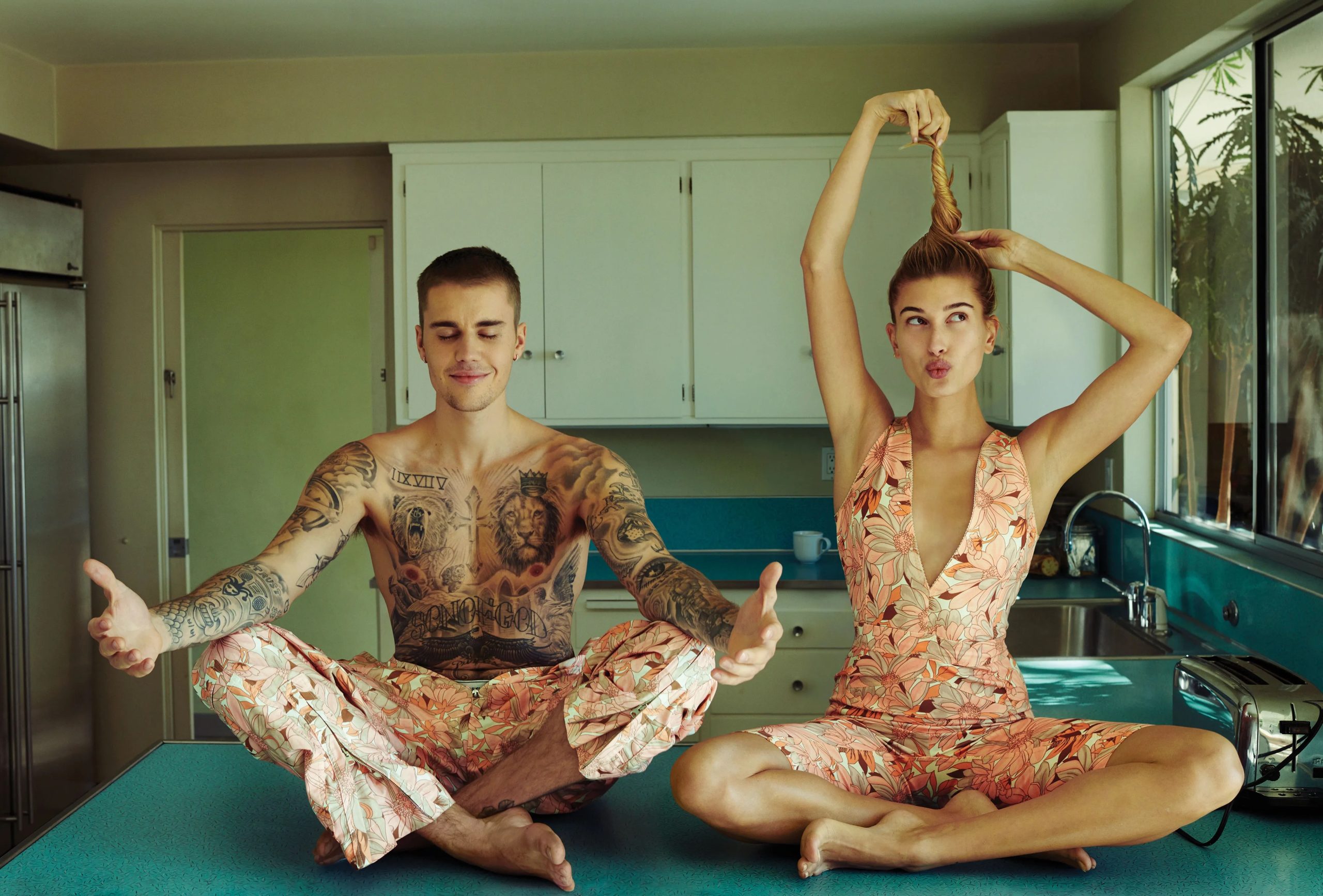

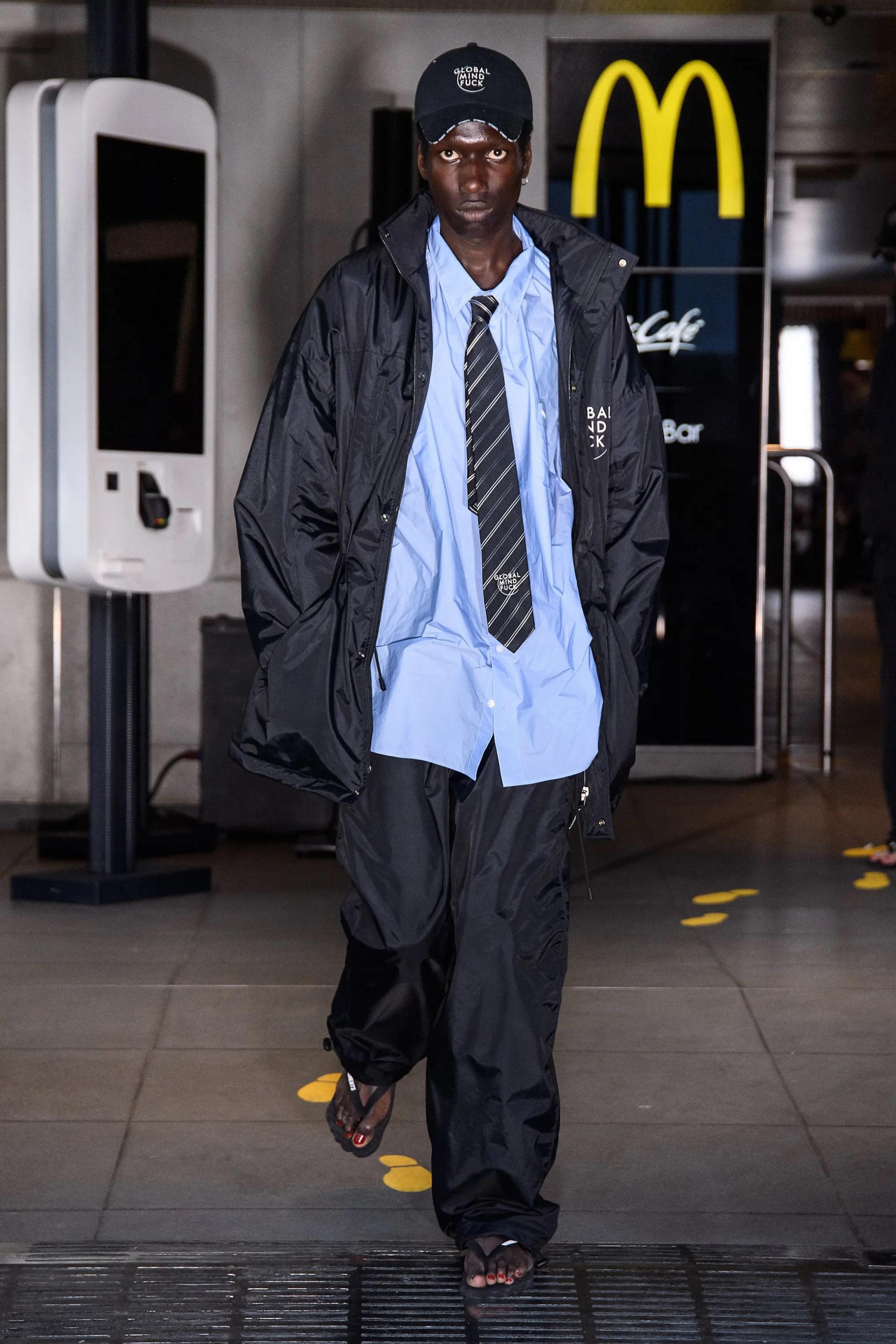

Yeezy is the epitome of high peasant, as well as current Balenciaga, or when your favourite celebrity does a photoshoot in a visibly low income/economically inclined location or posts themselves eating or consuming something that is traditionally associated with poverty or lack within our society.

Whether they truly do consume or participate in that activity — which acts as a signal of poverty in our society — is irrelevant because accessibility and target audience/perception are what determine aesthetic.

Let’s go more in depth with Balenciaga.

From 1997 to 2013 Balenciaga clothes were designed by Nicolas Ghesquiere. When Nicolas left he gave an interview to System Magazine, where they asked him why he left and he said:

It all became so dehumanised. Everything became an asset for the brand, trying to make it ever more corporate – it was all about branding. I began to feel as though I was being sucked dry, like they wanted to steal my identity while trying to homogenise things. It just wasn’t fulfilling anymore.

In the interview, he goes on to say that he became “Mr Merchandiser”. Soon after this realisation, Nicholas was replaced by Alexander Wang and long story short, Alexander was replaced by Demna Gvasalia who has creatively directed Balenciaga from 2015 till this day.

Demna’s work became really popular in the mid 2010s — especially on social media because as many speakers have theorised — Demna is very good at taking the “look” of the working class and transposing it onto the runway.

Balenciaga has now become a mix of all of its past creative directors work, super steered by this idea of turning everyday things into luxury — subsequently presenting them as “new things” due to the nature of high fashion. Therin comes the ‘high peasant’ theory and application.

As stated, high peasant is visually poor but actually has high construction and maintenance.

Rao speaks about this and states that, “High peasant is not actually peasant. It’s reconstructed fiction of peasant with high resources. Think of it as a pastoral art form.”

Fashion is a school of thought. Balenciaga thrives because, for better or worse, it acts as a treadmill for thought and sociological study through fashion — not only are they going but they’re going fast — not only are they going fast but I believe they’re going in the wrong direction. And not only are they going in the wrong direction, they’re taking us with them.

Some people appreciate the treadmill, they appreciate the rude awakening — they appreciate the talking points and the cultural backlog that Balenciaga brings to the table.

But all of that is futile to me when you consider the imbalance of our world today and what we pay attention to.

There’s a gross imbalance to what we want to achieve and what we’re actually accomplishing — drama over calm, individual over community, controversy over unity and war over peace.

Using signifiers associated with poverty to complete a high monetary value aesthetic romanticises actual reality which further puts people who live in poverty on the margins of society — therein the unequal suffering and pain appears to be less harsh or detrimental as it is.

This closely falls under the same category as gentrification — even though gentrification is actually the lack of intervention from the government/empowered bodies when such occurs.

It is interesting to watch the growing interaction between the wealthy and the vastly poor world. As Moree states; to the wealthy, “poverty seems like a rebellion instead of a reality”.